What I Learned From Going To Seventeen Nebraska County Fairs

Agricultural America on display.

Photos by Renée Lynn Reizman

My first Nebraska fair of the summer was Franklin County, a farm town with a population just under 3,000 that could rival my former high school in the Chicago suburbs. Their fairgrounds were modest, with the majority of the layout dedicated to barns, a showmanship ring, and a small arena for the open-entry ranch rodeo that would take place later that evening. In an exhibition hall, the 4-H displays overshadowed the adult open-class entries, and I maneuvered through plates of homemade apple crisp and chocolate chip cookies covered in plastic wrap, searching for the purple ribbon quilts, jams, sweet corn, and roses that would join more than 100 other categories at the State Fair at the end of August.

I came to Nebraska as an artist in residence on a farm in Marquette (pop. 232) to research the impact internet infrastructure may have on the aesthetics of quilting in rural America. Transplanted to a place where I knew practically no one, but determined to interview quilters and see their work firsthand in some of the most sparsely populated areas of the state, I visited county fairs. Over the course of eight weeks, I went to 17 fairs, plus the Nebraska State Fair.

I was expecting a lot of diversity in the fair circuit, with each county featuring their particular quirks in an exaggerated, kitschy celebration. But instead I witnessed the opposite, a county fair aesthetic that was consistent and manufactured, colorful yet banal. Contrary to what I was expecting, the diversity of attendees was apparent—Nebraska’s demographics are rapidly changing. Between 2000-2010, the minority population grew by 50.7% while the non-Hispanic White population went up by only .04%. In 2015, around 38% of the children born in Nebraska were minorities. And in 2016, Nebraska resettled the most refugees per capita in the nation.

The county fair homogeny instead sprouts from funnel cake stands, dairy cows, and the obligatory carousel. Present-day carnivals are modeled off the World’s Columbian Exposition, which took place in Chicago in 1893. The world’s fair was an extravagant celebration of new technology, innovation, and culture. Placed in the center of the expo was what became known as a “midway,” the main area dedicated to showcasing these feats. Here, Eadweard Muybridge demonstrated his early moving picture machine, the zoopraxiscope, creating the first commercial movie theater. Josephine Cochrane, founder of KitchenAid, inspired homemakers with her debut of the dishwasher. An entertainer known as “Little Cairo” introduced Americans to bellydancing. The midway brought the Ferris Wheel to awestruck attendees, and for some, its nightly light display was the first they saw electricity in action. Today, the rides are still illuminated with round, multicolored bulbs that glitter into the night, the game operator never stops trying to seduce you into throwing a ring around a bottle with her eloquent carnival cant, and you can always count on your favorite candy bar, or compressed meat product to be fried and served on a stick.

To create the distinct modern-day fair atmosphere, there needs to be a midway, a section with carnival rides, games, food, and entertainment; and there needs to be a grandstand and a cluster of barns, stables, and exhibition halls to hold the competition entries made up of livestock, agriculture, horticulture, culinary, craft, and fine art. Aesthetically, the splashy midway embraces the faux-opulence of the Gilded Age, which was thriving when fairs began to take off. This means adorning the house of mirrors with cheap, but ornate stucco carvings, hand-painting a mural of the Garden of Eden on the top of a carousel, and hawking ice cream out of booths decked out in high-key colors of cotton candy pinks and blues, with large, swooping calligraphy hailing everything as the “World’s Greatest.”

In Nebraska, the feeling of déjà vu from fair to fair is owed in part to the family-owned D. C. Lynch Shows, which was founded in 1957 and operated the carnival for 11 of the 91 county fairs in the state this year. From Broken Bow to Norfolk, D.C., Lynch brings the same glitzy tilt-a-whirls and scramblers to eager fairgoers. “It’s not a carnival without a merry-go-round and a ferris wheel,” said Mike Lynch, a third-generation member of the family business. A county like Franklin, located in South Central Nebraska and holds its fair in the county seat Stockville (pop. 25) had one of the smallest selections of rides and games to choose from, still captured the energy of the fair, because it had these staples. In contrast, Hooker County, which lies in the heart of the Sandhills and whose county seat, Mullen, is also the only town in the entire county, didn’t have a carnival at all. Walking around Mullen’s compact fairgrounds felt like sneaking into a stranger’s family reunion because I couldn’t resist the smell of their beef brisket. It was obvious I didn’t belong there, and a couple of concerned volunteers asked me if I needed help. Had I been hovering around a corn dog stand or chucking a baseball at a tower of milk bottles, there would have been fewer questions, and maybe the assumption that I was distant cousin visiting from another town.

Though the carnival offers modern entertainment—a towering chainsaw amusement ride known as the Zipper, a House of Mirrors painted with bootleg characters from Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, the music not ragtime but Selena Gomez’s latest hit—the county fair finds a way to be timeless by offering the same attractions in different packaging. The shooting gallery might incentivize young marksmen with giant plush Minions, but kids still win their prizes by shooting a BB gun at small, star-shaped bullseyes. “One nice thing about the fair is electronics haven’t taken over completely,” Lynch told me. “Kids can do what [their parents and grandparents] enjoyed, and do that as a family.” And now, with the social and economic landscape changing in the most conservative states in the nation, the county fair, despite all its charm and wonder, embodies the spirit of “Make America Great Again.” Fairs maintain an antiquated aura that doesn’t reflect a shrinking rural population, a threat of automation, or an opioid crisis ravaging small towns.

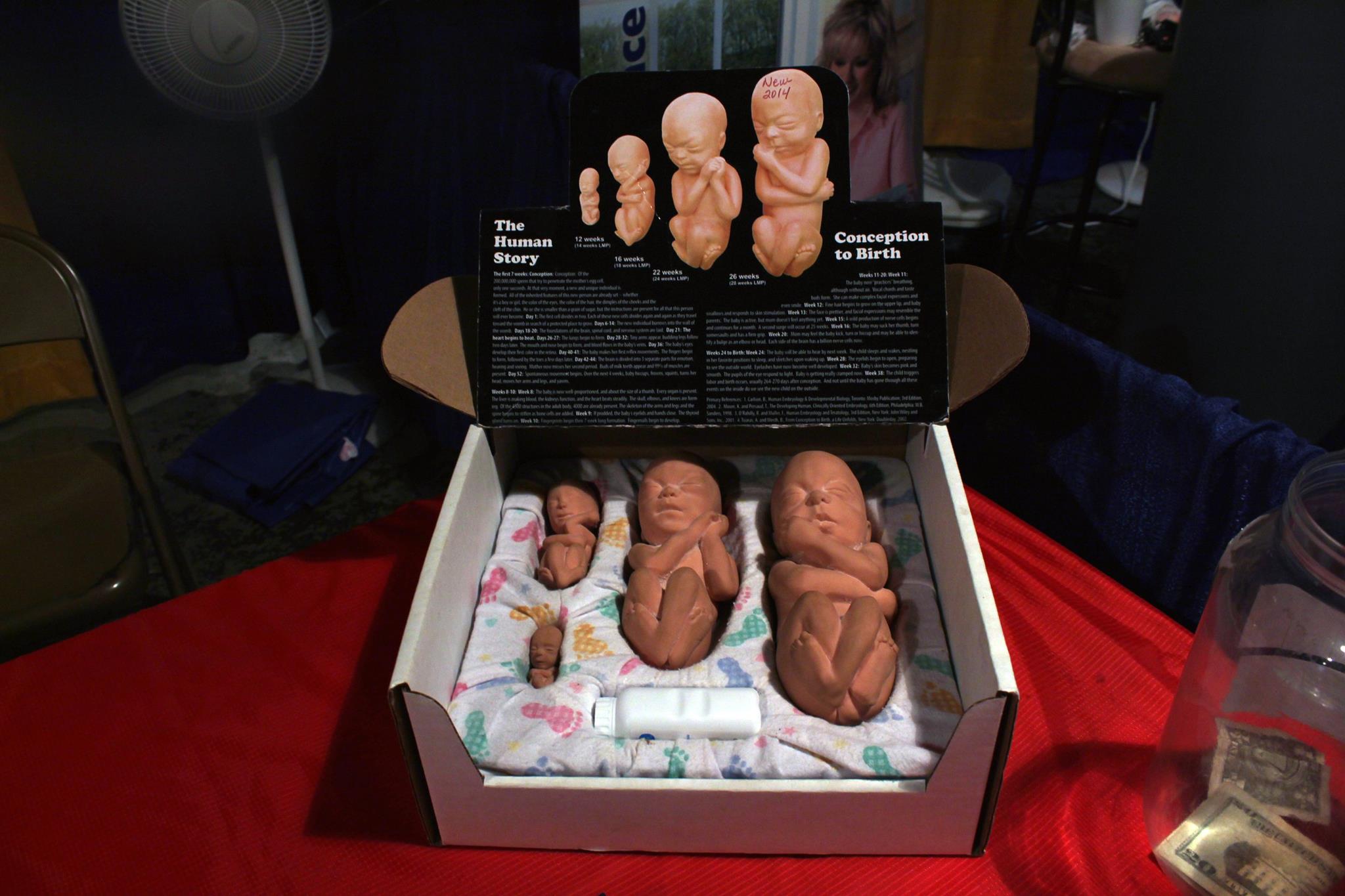

Part of what makes a county fair so valuable for a rural community is that it serves as a place to help reinforce and confirm what are perceived as diminishing conservative values. Before the cowboys took the stage at Nebraska’s Big Rodeo in Burwell, I listened to the announcers say a prayer invoking Christ. In Columbus, a pro-life exhibitor invited me to pick up anatomically inaccurate reproductions of fetuses and see how large they would be inside of me at weeks 6, 8, and 12. When I spoke to people in remote towns like Llewellyn (pop. 211) and Chambers (pop. 263), and shared that I was a graduate student in Los Angeles, I was met with what I viewed as unprompted defensiveness. Some immediately labelled themselves “old-fashioned” before answering any of my questions. Others would make excuses for the entire state, making sure to let me know that, compared to everywhere else in America, Nebraska was ten years behind on everything from fashion to infrastructure.

Conservative rural Americans are hyper-aware that they hold polarizing views on social issues in comparison to urbanites, and the county fair is one domain where they don’t have to hide them. Confederate flags were displayed proudly on pickup trucks rumbling into the dirt parking lots. (Nebraska fought with the Union army, but was not part of the United States during the Civil War. 2017 marks its 150th year of statehood, meaning it was still a territory at the time.) On multiple occasions, I had the chance to come home with a brand new rifle if I bought a ticket for the charity auction. Quilts of Valor, which are usually raffled off to raise money for veterans, are still one of the most popular type of collaborative craft project, and Star Spangled themes dominate the purple ribbons in everything from woodworking to photography. For a politically progressive outsider, there’s an overbearing sense that you are guest in someone else’s home. The most kinship I could build with others was by talking about the Air Force veterans in my family.

Many middle-American farmers were granted their land by the Homestead Act of 1862, and were placed in barren landscapes along the High Plains without agrarian training. Building a successful working farm after braving harsh climate, disease, and remote resources formed a culture of independence that benefitted from the possession of firearms, unwavering faith, and a distrust of a government that promised free land without disclosing that it was nearly uninhabitable. Over 60% of homesteaders abandoned their plots, but those left behind grew into multi-generational families of farmers that are proud of what they did to become self-sufficient.

That preservation instinct plays a big role in maintaining the other half of the county fair aesthetic: the agricultural exposition. Outside the midway, the county fair aesthetic isn’t so much about nostalgia as it is about displaying a culture that isn’t replicated anywhere else. County fairs are a continuation of American Agricultural Fairs that started long before the carnival took center stage. 4-H and Future Farmers of America are the backbone of the fair, cultivating a youth network that masters the skills of agriculture, domestics, and fine arts that are honored in the community. Exhibiting these works shows another side to rural sensibility that can’t be accurately captured in the ephemeral carnival next door. The livestock are kept in sturdy pens, nearly identical across county fairgrounds, steel barred enclosures that allow a hand to reach through and beckon for a Boehr goat’s attention. Sometimes the owner spruces up their area with a hand-carved sign advertising their ranch, but for the most part information is presented with banal printouts letting visitors know the purple ribbon-swine’s stats.

But the magic of a county fair is not lost in the grandstand and barns. The efficient segmentation of livestock is equally part of the rural aesthetic, a reminder that farming and ranching is harsh, hard work. The idyllic farmhouse sitting on green pastures is maintained by backbreaking labor, an infallible work ethic, and a hard-learned emotional detachment from the livestock and crops they so carefully raise in order to sell year after year. I overheard a young 4-H’er at the Frontier County Fair, who had won a blue ribbon for her Angus cow, and was preparing her companion for auction, speaking to boy from another club. “You’re lucky you don’t show cows. There’s lots of tears involved.”

Evidence of the dwindling focus on agricultural roots come from fairs that are searching for ways to offer entertainment and services to the increasing number of non-agrarian attendees. Now, a rural county fair might introduce people to virtual reality, teach Somali refugees how to auction a goat, or swap the nightly entertainment from country music to reggaeton. At the Lancaster Super Fair, the largest county fair, located in the capital, Lincoln, the usual group of livestock was supplemented by an exotic petting zoo. The repetitiveness of sheep was interrupted by the presentation of a camel, kangaroo, and capuchin monkey who desperately tried to break a padlock he thought to be trapping him in his cage. Fairgoers watched in amusement while they exchanged dollars for feed, bribing a pair of antelope for their affection. There was an inarticulate sadness to the petting zoo; I discovered a counterintuitive preference for being around the livestock I knew would be sold and butchered. Even though the animals have a grim future, they’re still raised with love and diligence. The romanticization of rural life incorporates a utilitarian sense of responsibility—this is how it needs to be for us to survive.

The county fair is a perpetual machine; as soon as it ends, the planning begins again, with the core elements intact. The competitions are spoken for, the fairgrounds are already built, the rides will be dispatched from a carnival behemoth’s warehouse that serves half the state. Lynch says that the fairs are sometimes the family get together of the year, and relatives who long left Nebraska return to their hometowns to carry on the tradition. There’s comfort in stability, and one can look forward to the county fair in the same way one waits for Christmas to arrive. One thing I learned is that, even after 18 fairs, I never get tired of petting goats, and demolition derbies are more thrilling than I could have ever imagined. The fair will live on into an uncertain future, and maybe one year I’ll take home a purple ribbon in something my city-slicker self can master.