Cormac McCarthy On the Unconscious Is The Coda To His Career

What can we learn from his nonfiction?

“The Kekulé Problem” by Cormac McCarthy in the April issue of Nautilus is the author’s first foray into non-fiction, and it’s utterly bonkers.

Never one for pumping out content for the sake of it—the last thing he published was 2006’s The Road, unless you count the screenplay for Ridley Scott’s 2013 movie The Counselor—McCarthy sets his sights on tackling, or at least knocking around, one of the universe’s bigger mysteries: Where does language come from?

According to an introduction by David Krakauer, President and William H. Miller Professor of Complex Studies at the Santa Fe Institute, McCarthy has been kicking around the halls of the SFI for two decades, examining the “puzzles and paradoxes” of language and the unconscious mind. The 3,000-word essay is the result.

Looking back on his career, you can tell he’s been obsessed with these concepts, if only because of what his novels have continually left out. McCarthy’s always been stingy when it comes to insights into the minds of his characters. A free flow between external description and internal thought is one of the tools most often used by authors—it is, perhaps, one of the reasons that fiction exists—yet McCarthy rarely does. (In this way, it makes sense McCarthy has dabbled in screenwriting: His style is similar to films without voiceover narration, while his long sentences—like, that 245-word “legion of horribles” description in Blood Meridian—work like unbroken camera shots in the reader’s mind.)

Arguably, the only time McCarthy’s made an effect to examine a character’s mind was in 1979’s Suttree, a series of seemingly disconnected incidents that befall Cornelius Suttree, a misfit who’s left behind his wife, child, and steady life to live on society’s fringes on a Tennessee River houseboat. It’s easily his funniest novel, and also his most autobiographical—written over 20 years, you can tell he’d walked the streets. Seeing as Suttree is somewhat of a McCarthy stand-in, perhaps he allowed himself to blend description and thought because he felt justified, since many of Suttree’s thoughts are likely his own.

In the first few pages, this is how McCarthy describes his character entering a dream:

He crossed the cabin and stretched himself out on the cot. Closing his eyes. A faint breeze from the window stirring his hair. The shantyboat trembled slightly in the river and one of the steel drums beneath the floor expanded in the heat with a melancholy bong. Eyes resting. This hushed and mazy Sunday. The heart beneath the breastbone pumping. The blood on its appointed rounds. Life in small places, narrow crannies. In the leaves, the toad’s pulse. The delicate cellular warfare in a waterdrop. A dextrocardiac, said the smiling doctor. Your heart’s in the right place. Weathershrunk and loveless. The skin drawn and split like an overripe fruit.

The feverish dreams occasionally continue throughout, climaxing at the novel’s end, when Suttree experiences near-death hallucinations due to a bout with typhoid fever.

His delirium takes the form of a trial. When confronted with the accusation that he’s wasted his life, Suttree’s first excuse is, “I was drunk.” (McCarthy quit drinking around the same time that Suttree was published, saying that, “if there is an occupational hazard to writing, it’s drinking.”) Then come the moments of clarity: Suttree discovers “all souls are one and all souls lonely,” that God is “not a thing,” that “nothing ever stops moving.”

These truths reveal themselves at “the very edge of consciousness,” those undiscovered places where insights into our own humanity roam in their most purified, removed from the trappings of language that contort, diminish, confuse. Sometimes, an emotion can be further elucidated by putting it in words. Other times, it can be suffocated. Think about the last truly emotional dream you had, and how quickly it vanished when you tried to describe it. This, after all, is why other artistic mediums exist.

McCarthy, as a writer, has forever danced with this problem: How do you write about the revelations from the unconsciousness when it doesn’t use language? Which takes me back to a singular moment in the Nautilus piece, found no where else in his career. See if you can pick it out:

What is at work here? And how does the unconscious know we’re not getting it? What doesnt it know? It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the unconscious is laboring under a moral compulsion to educate us. (Moral compulsion? Is he serious?)

Part of McCarthy’s stinginess has, famously, been his self-governing punctuation rules. Some of that’s simply style; he doesn’t want to clutter up the page with quotation marks or semi-colons. But it’s also about maintaining a disciplinary focus on what he allows himself to describe. By handcuffing himself, he’s forced to present observations without bias, almost like a documentarian or reporter. (If you don’t have parentheses at your disposal, you can’t write parentheticals!) That’s what makes his use of parenthesis in the above passage so notable.

What the hell do parentheticals do anyway? They’re oddities, digressions that seem necessary to include, but not vital enough to fit more adeptly. They’re informative, but nonessential, more throwaway than functional. They’re the first passages cut when up against a strict word count, but if we’re being honest, even then somehow find a way to muscle themselves in. Maybe their inclusion is sentimental, that mug with a crack stuck in the back of the cupboard rather than thrown away. Maybe the writer doesn’t know why the parenthetical stayed in, torn pages from a diary they didn’t know they were keeping.

So, why did McCarthy use parentheses here? Who knows. Maybe he even doesn’t, not entirely. And that’s sort of the point. Parentheses are our best representation of that murky space between language and thought, a grammatical link between conscious precision and putting one’s trust in the unconscious as it tries to figure out how to use language. And McCarthy, in what is surely to be one of his last completed works, finally found proper justification to use them.

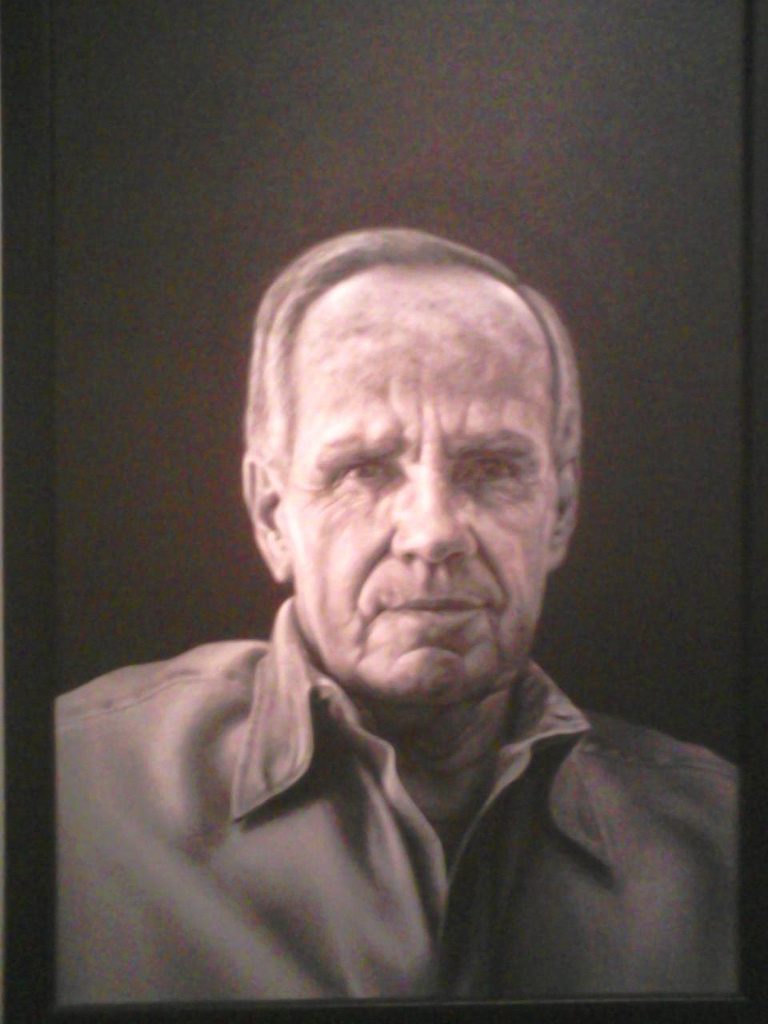

Image: Wei Tchou via Flickr