How To Write Music For Your Lost Love

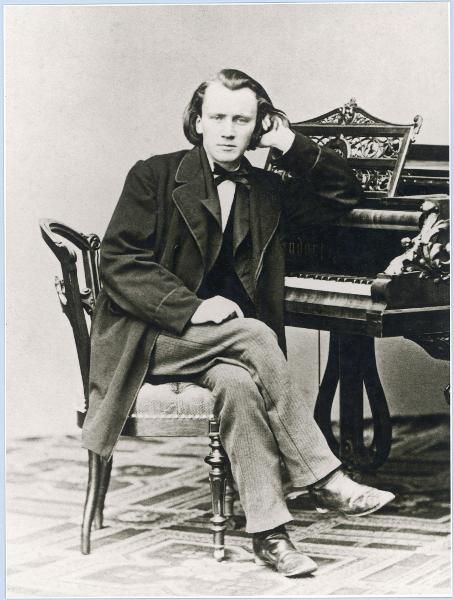

TFW it’s Brahms.

Ha ha, remember when I only wrote about Brahms? Times were different back then—well, not really, but it’s nice to pretend they were. As it turns out, I’ve got Brahms on the brain again, because I just finished reading the excellent Call Me By Your Name (which will be a movie of the same title later in the year), in which the young protagonist, Elio, finds himself transcribing old Brahms compositions throughout the novel. Elio, like Brahms, is quite good at piano, but the piece I wanted to write about this week is actually the composer’s String Sextet No. 2 in G Major (Heifetz, 1963), written for a lost love.

Brahms had numerous affairs in his life, which I don’t mean in an “The Affair, only on Showtime” type of way, but more in the 19th century type of affair that involves a lot of letter writing and not a ton of kissing. In the spring of 1858, Brahms and his pal Clara Schumann took a vacation to Göttingen together to see his old friend Julius Otto Grimm. Brahms had not wanted to go on vacation at the time, but trudged along anyway, only to find that Grimm and his family spent time with a lot of young beautiful female singers in their early twenties. Like some Pitch Perfect shit, I don’t know. So Brahms meets a young soprano named Agathe von Siebold with whom he is immediately taken.

The romance doesn’t work out, because when does it ever in the past? But Agathe provided Brahms with years of inspiration for his music, going so far as to inspire one of the central themes of his String Sextet in G Major. In the event you are confused by what a sextet is—or if you really have only read to the word “sex” and found yourself totally lost—allow me to illuminate: a sextet includes two violins, two violas, and two cellos. (The more accepted plural for cello is “celli” but I can’t bring myself to type it out, sorry.)

Its opening movement, the Allegro non troppo, is warm and bright with a deep undercurrent of unrest permeating throughout. Sort of feels like that’s Brahms’ big thing, huh? The nice thing about this sextet is that it’s not quite as tortured as the symphonies nor is it as broad and ambitious as the piano concerto, but it definitely is a display of emotional depth. In having duplicates of each instrument, Brahms is able to create a divide between two parallel sounds—differing melodies, textured accompaniments. There’s a constant state of conflict throughout.

But there is great beauty too. The second movement, a Scherzo – Allergro non troppo, opens with a wistful but upbeat melody that plays like a dance. I love the repetition of this particular movement. It’s like having an obsession, a song that plays over and over again inside your head. And I love the 2:53 mark where it feels like it’s slipped into something else entirely, like waking up from a very realistic dream or splashing your face with cold water. There are these little crescendos that occur at the 3:48 and the 3:51 mark—as if Brahms is forcefully trying to make himself snap out of a daze. It doesn’t work, however, however: the Poco Adagio, the third movement fully indulges in the obsession. It’s almost dizzying in its loveliness.

The fourth and final movement, the Poco Allegro, is the biggest and broadest of them all. By now you know the central melody at heart, and it plays out like a little waltz. Here is where I do a big reveal, though, which is that did you realize, in listening to this piece, that the notes being played spell something out, and what they spell are:

AGA(D)HE

And I know you, so you’re very ???? right now. Well, calm down. Let’s think about this. AGA—hm, kind of how “Agathe” starts, so far so good. And then you’re like (D)? Why is the D in parenthesis, first of all? Well, it’s because they’re in the accompaniment, so they’re beneath the central melody. But if you close your eyes and think very hard, you can imagine a D is kind of like a T, or they rhyme. At least that’s how Brahms deals with that logic. And then you’re like H??? Is not a note??? In music??? You dunces: H is the German name for B. And then it closes on an E. So you quite literally have an AGATHE theme that permeates the entire piece.

This sextet is about Brahms’ obsession and forgiveness and ultimately he used it to forget Agathe after their affair. It’s a good example of the way melody can be used extremely literally without the use of lyrics. It becomes a social act. It becomes your “I’m finally ready to move on” tweet. Because after this, also, Brahms doesn’t write about himself so much or the things around him. It freed him of the urge to put himself forward and allowed a much introspective artist to come through.