The Penny Paper Sex Scandal

Edwin Forrest and the rise of the celebrity divorce case.

In retrospect, assaulting his estranged wife’s alleged lover with a whip probably wasn’t the best way for star actor Edwin Forrest to enhance his image during his difficult and very public divorce. Magazine editor Nathaniel Parker Willis received a vicious thrashing when he had the bad fortune to encounter Edwin on Washington Parade Ground (now Washington Square Park) on June 16, 1850. Edwin threw Willis to the ground, placed his foot on his neck, and began beating him, yelling to bystanders, “Gentlemen, this is the seducer of my wife; do not interfere!” Ultimately, Edwin was in for a far worse pummeling at the hands of public opinion. His attack on Willis gave additional fuel to the newspaper editors who were busy turning this dispute into one of the United States’s first major celebrity scandals.

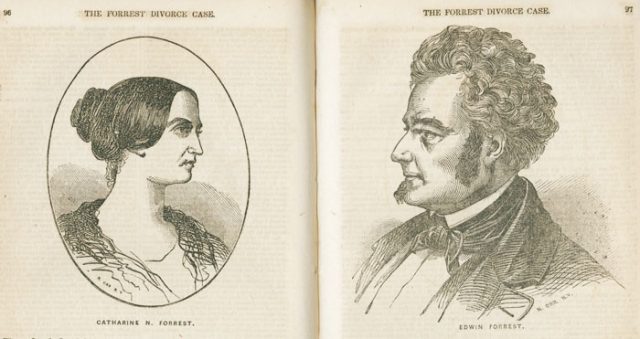

When Catherine Norton Sinclair married Edwin Forrest in 1837, he was arguably the most prominent actor in the American theatre. He embodied the spirit of the age of Andrew Jackson: his acting style was physically vigorous (to a fault, his critics said) and the characters he played were bold in spirit, evincing more emotional intensity than intellectual depth. In addition to the usual repertoire of Shakespearean characters, he also commissioned American authors to write plays with distinctly American roles for him, such as the title character in Metamora; or, the Last of the Wampanoags. Metamora was a Native American chief who functioned as the archetype of the doomed Native American—a noble savage fated to conveniently fade away before the rise of an Anglo nation. The play, which premiered around the same time as the events that would lead to the Trail of Tears, was a hit.

The support of the rapidly changing American media helped fuel Edwin’s rise. In the 1830s, “penny papers” began replacing cumbersome broadsheets, which had mainly concerned themselves with political and business news aimed at an elite readership. The new, cheaper, and more portable breed of papers served the growing ranks of literate, middle-class readers, publishing stories that emphasized sensation and salaciousness. The most notorious of them was the New York Herald, which vaulted to prominence with its breathless coverage of the sordid details of the murder of prostitute Helen Jewett, and whose editor, James Gordon Bennett, earned a reputation for ruthlessness and unscrupulousness. Edwin’s emergence as the nation’s first celebrity actor made him a sympathetic figure whom Bennett could promote to his readers – for the moment, at least.

Having achieved stardom in his homeland, Edwin set off to conquer Europe. While in London, he met and married Catherine, the intelligent and sophisticated teenage daughter of a family of performers. As Forrest’s biographer Richard Moody notes, their wedding banns were announced in the British papers in between the requisite black bands that solemnly acknowledged the recent death of King William IV, which a more superstitious couple might have taken for a bad omen.

The Forrests settled in New York, where Edwin’s star continued to rise. In the meantime, Catherine staked out her own place among the city’s literati, building a circle of acquaintances that included accomplished writers and intellectuals such as Willis, journalist and proto-socialist Parke Godwin, and the actor George Jamieson. Together, they discussed culture and books, such as George Sand’s Consuelo, in lively conversations that often lasted late into the night. Edwin, however, stayed away from Catherine’s circle of friends, a move that presaged trouble. By 1849, the Forrests’ marriage was falling apart. The point of no return came on January 18, when Edwin greeted Catherine’s return from a late-night gathering with a stunning verbal assault, which ended with him declaring that their marriage was over.

Catherine soon realized that Edwin had gone through her papers, where he’d found a letter from Jamieson, which addressed her as the title character of Consuelo. The letter sent Edwin into a jealous rage:

And now, sweetest Consuelo, our brief dream is over – and such a dream! Have we not known real bliss? Have we not realized what poets loved to set up as an ideal state, giving full license to their imagination, scarce believing in its reality? I have; and as I will not permit myself to doubt you, am certain you have.

It went on from there, ending in florid poetry that asked, “When next we meet,/ Will not all sadness then retreat,/ And yield unconquered time to bliss,/ And seal the triumph with a kiss?/ Say, Consuelo.” The poem brought Edwin back to an incident the previous year, when Jamieson had happened to be on tour in Cincinnati at the same time as the Forrests. Edwin had returned from an appointment to find “Mrs. Forrest standing between the knees of Mr. Jamieson, who was sitting on the sofa, with his hands upon her person.” Jamieson had just attended a lecture on phrenology with the Forrests and, when Edwin questioned him, he claimed to have “been pointing out [Catherine’s] phrenological developments.”

By the end of April, Catherine had moved out. They were unsure of their next move: should they get back together? Finalize the separation and make it official? Such questions would have to wait until the fallout from another, far deadlier, incident involving Edwin had settled.

Back in 1836, during the same European tour that introduced him to Catherine, Edwin’s performances attracted the disdain of theatre critic John Forster, a friend of William Charles Macready. Edwin thought Macready, the premier English actor of his time, was behind Forster’s criticism, which eventually led to him hissing at Macready’s interpretation of Hamlet in Edinburgh in 1845. That set off a running feud between the two actors’ supporters, which intensified when Macready came to the United States in 1848 and 1849.

According to Macready’s diary, audiences threw a “copper cent” and “rotten egg” at him in Boston and “the half of the raw carcase of a sheep” that someone managed to smuggle into a theatre in Cincinnati and launch onto the stage. By the time he reached New York, which was crawling with Forrest’s diehard partisans, Macready was in very real danger. He had to dodge a hail of objects onstage at the Astor Place Opera House on May 7: more copper cents and eggs, apples, lemons, “a peck of potatoes,” and even some of the venue’s chairs. By the next night, his assailants had been forced out of the opera house, but they gathered outside and sent volleys of rocks through the theatre’s windows. The city government called out the militia, who fired into the crowd and killed nearly two dozen people, an event that came to be known as the Astor Place Riot.

The riot also marked a turning point in Edwin’s career. Many in New York’s upper classes considered him at least partially responsible for the bloodshed. Edwin had never been able to escape the perception that he represented some of the worst impulses of Jacksonian America: not only did his brawny acting style compare unfavorably with Macready’s refinement, but his sometimes violent supporters raised the specter of mobs who might direct their rage against non-whites, foreigners, or out-of-touch urban elites.

As the fallout from the riot died down, Edwin and Catherine made halting attempts at reconciliation in the fall of 1849. But they came to nothing, and both sides hired lawyers. The two parties claimed to want to keep things civil, but when Edwin’s lawyers then accused Catherine of “criminal acts inconsistent with the dignity and purity of the marriage state.” Charles O’Conor, Catherine’s high-powered, politically connected lawyer, cried foul.

The rise of the penny papers meant that it was an especially bad time to be a celebrity couple going through a divorce. With Edwin’s reputation damaged by the Astor Place Riot and Catherine’s under suspicion because of her husband’s allegations against her, both Forrests soon found out how bad things could get when the popular press got a whiff of scandal. Bennett’s Herald got its hands on the Forrests’ personal correspondence and, in early April of 1850, the “Consuelo” letter appeared in newspapers nationwide, along with lots of other embarrassing material. The circle of Catherine’s alleged lovers widened to include Willis, Jamieson, and six other increasingly implausible suspects. Willis responded in the pages of the Herald, as well as in his own magazine, the Home Journal, casting doubt on Edwin’s character. Edwin had never much liked Willis anyways: the Journal focused on domestic, middle-class subjects such as fashion and women authors, hardly the sort of thing that a red-blooded American male should be wasting his time on.

Edwin’s assault upon a refined gentleman like Willis made him look uncouth and thuggish, and the press eagerly set about advancing this image. Catherine made an unsuccessful request to have him arrested because his unhinged behavior was beginning to make her fear for her personal safety. The night before Edwin assaulted Willis with a horsewhip, he’d encountered yet another of Catherine’s alleged lovers, Samuel Marsden Raymond, outside her residence. According to later court testimony, Edwin threatened Raymond, bellowing, “I have a terrible reckoning with you and some others; I have marked the damn scoundrels, and will have vengeance on every one of them. Damn you, you have been there to-night, (here a present participle was used) Mrs. Forrest.” Catherine’s lawyers introduced an affidavit stating that there was a very real danger that he might kidnap her in order to forcibly bring her to Pennsylvania, where he’d initially filed for divorce.

Catherine’s lawyers then filed for divorce in New York, alleging infidelity on Edwin’s part. Edwin upgraded his legal team, drawing on the services of John Van Buren, son of former president Martin Van Buren and, until recently, Attorney General for the state of New York. When the case finally reached court in December of 1851, the jury was asked to consider the question of whether either of the Forrests had committed adultery, which led to a series of embarrassing public testimonies, which papers like the Herald eagerly reported (and later collected together and sold in pamphlet form). However, the best that Van Buren and his team could establish was that Catherine had a number of male friends who liked to stay up late and drink a lot. Catherine’s lawyers also called Edwin’s sexual promiscuity into question, alleging that he frequented brothels and had been sleeping with the late actress Josephine Clifton even after his marriage.

Finally, on January 26, 1852, the jury announced a verdict: Edwin was guilty of adultery. His and Catherine’s supporters, now noticeably divided along class lines, either cheered or lamented the verdict accordingly. When Edwin played the Broadway Theatre on February 9, his fans roared their approval of him, unfurling a banner that read, “THIS IS THE PEOPLE’S VERDICT.” Catherine’s supporters were quieter, but in the long run their feelings may have counted for more: Edwin’s career never recovered, and he spent years dealing with the legal fallout. Ordered to give Catherine $3,000 in alimony, he ended up paying even more when he refused and lost his subsequent appeal. He died on December 12, 1872, still famous but with his finances and reputation considerably reduced. In the meantime, Edwin Booth, older brother of the infamous John Wilkes Booth, had usurped his place as the most popular actor in the country, in part because he had a more refined style of acting.

Short on funds because of Edwin’s stubbornness, Catherine turned to acting soon after the divorce. The attention that she’d received from the media during the split from her ex might have been unwelcome, but at least it lingered long enough to help get her acting career off to a successful start. She went on to act in and manage theatres in California, tour Australia and London, and retire just before the Civil War. She lived until 1891. Despite her accomplishments and her interesting personal life, she’s never received a fraction of the attention that Edwin has garnered from historians.

As for the penny press, its role in the Forrests’ divorce presaged bigger things to come. Even as Catherine and Edwin fought in the courts, savvy promoters like P.T. Barnum were using papers like the Herald to promote their touring acts, while the market for celebrity gossip kept growing. When Hollywood began minting movie stars in the twentieth century, there was already a thriving media complex, ready to serve up their triumphs and scandals for the public’s eager consumption.