Trump Tower, Manhattan

You don’t deserve attention. You can stay a stranger.

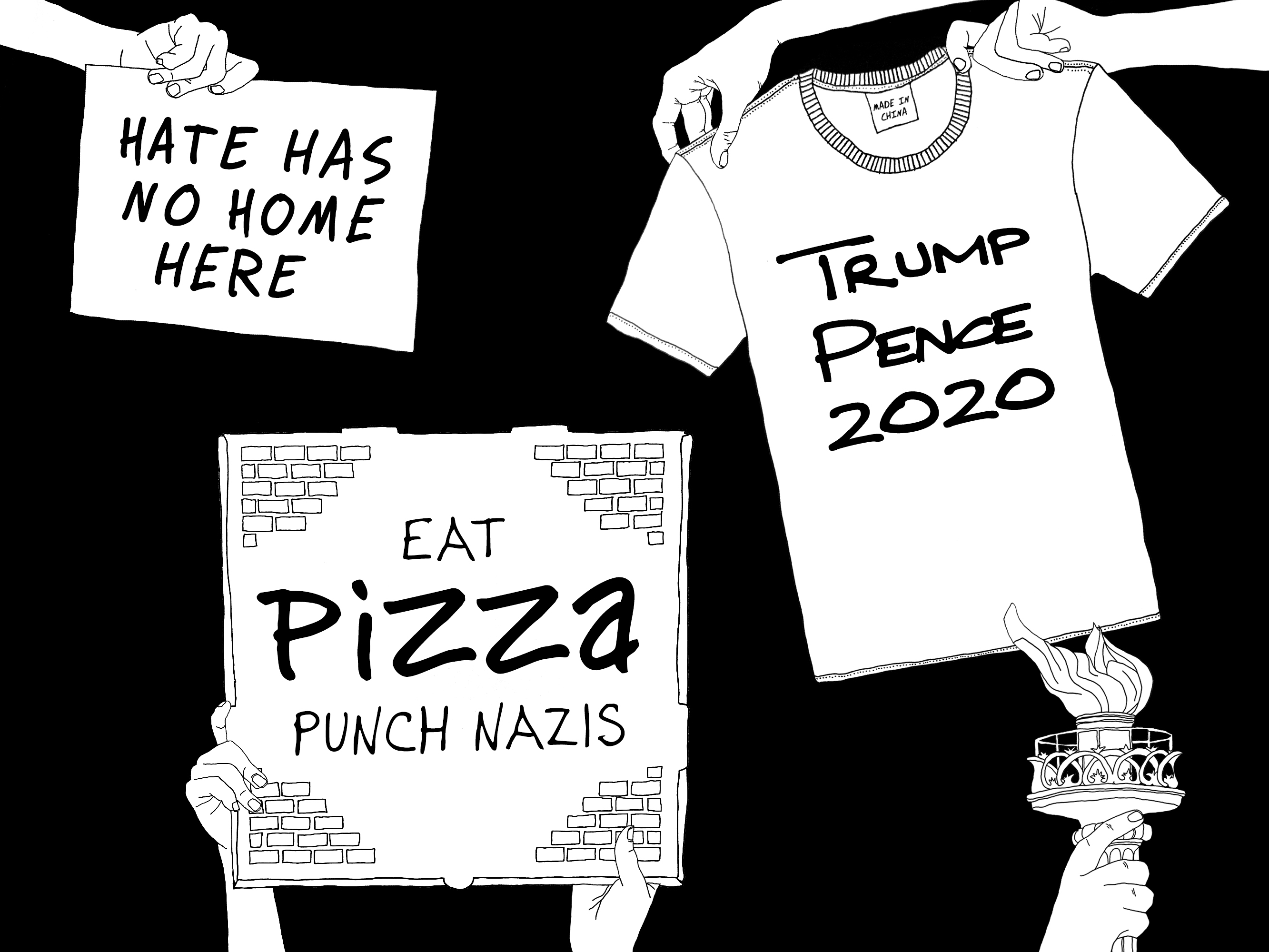

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

The tower is surrounded by garbage trucks. This is a fact. The metaphors, in being so cheap and egregiousness, are effectively dead at this point. Because for all the unconscionable things we could—and do—hate that man in his fucking gold-plated tower for, this lesser crime is among them: that, in being awful beyond compare, he’s essentially killed off metaphor and simile. Garbage, for example, is an epithet too good for him. You can make compost out of garbage, you can pick through it and recycle things. I can’t see anything redeemable here.

In front of the garbage trucks and the tower the police are wide-stanced with guns, facing us. They look like bad actors. The whole thing is a bad movie. “Is he in there?” someone asks. Yes. We hope so. There’s a roar of good energy and heads lift up to follow and find the source: a man and a woman, inside on one of the lower floors of the tower, holding up pink signs to the glass that say, “Hate has no home here.” We’re barricaded in on 56th and 5th and one friend, as regal a person as I know, texts from an also-barricaded block away to confess she just screamed “you’re a cunt” at a Trump supporter. She couldn’t help herself, she adds, and I know. Another friend, whose silvery blonde hair is newly buzzcut, baring her head, holds up a pizza box on which she’s sharpied “Eat Pizza Punch Nazis”; I look up at this exhortation and then down to the nape of her neck, which bears the word “Love” tattooed in large and elegant black cursive.

There is screaming, a fray and I feel the energy as a shock of heat before I turn and this is when I see you, or rather barely see you, because you’re crouched, and mobbed by middle-aged women striking you and yelling as you scuttle away. But in the scuffle I get a glimpse of your T-shirt, “Trump Pence 2020”. I haven’t hit a person in my adult life. I hope I never do. But I envy those middle aged women for how good it must feel, the discharge of fury as their fists find your young and hate-filled body. Maybe they think they really are beating the crap out of you—the crap of misogyny and racism and the rest. I wonder if you’re relishing these blows for presenting you with a vindication of your own hate, whether you’re feeling a peevish triumph. It could be that people thirst to receive violence as much as they do inflict it.

Police begin to announce their intent to arrest, their voices flattened and affectless over loudspeakers. Out where the crowd thins there’s a white-haired woman in her seventies raging at a policeman in the middle of the street. “Germany nineteen thirty nine!” and then she takes a long breath ragged with sobs and screams it again, louder, “GERMANY NINETEEN THIRTY NINE!” We stand and watch her, reluctant to leave, unable to stay.

One block further and there you are again in your too-tight Trump t shirt. This time, you’re breathless and babbling into the microphone of reporter who stands a good few paces from you, his face vacated of sympathy, arm held out long with the mic, a grim conduit for your ignorance and mania. I slow a bit, enough to hear you whine, “all of these losers” and I stare at you like there might be something in your face that will help me understand.

Because aren’t I doing this thing, writing these things, with some kind of empathic intention—to honor strangers with their due humanity? An intention which may be naive or delusional, but also seems to be a newly urgent moral duty. This, though, is what I understand as I pass and hear you say “all of these losers”: that you’re beyond my understanding. That just as I chose not to punch you in the face, I can also chose not to struggle to invest you with tenderness, to try and understand and redeem you. That seems as fruitless and misguided as punching. There is no moral equivalence between Nazis and those who oppose them, say the signs and the tweets, reminding us of these obvious truths that now, somehow, need restating. There is no moral equivalence, either, between those who defend Nazis and those who oppose them. You don’t deserve attention. You can stay a stranger.

Just before the subway we pass two improbably beautiful young men in tiny shorts kissing, oblivious, placards at their feet and hands in each other’s hair, and I stop and stare. I feel like a bored tourist in a museum who just turned a corner and came upon a breathtaking painting: I’m dumbfounded by a sense of deliverance, ravished. I remember George Saunders at the Trump rallies, staggering out of a ugly fray and coming upon a wedding in a mini-mall. He falls into the conditional tense at the sight. “Up will walk the bridesmaids, each leading, surprisingly, a dog on a leash, and each dog is wearing a tutu, and one, a puppy too small to be trusted in a procession, is being carried, in its tutu, in the arms of its bridesmaid. And this will somehow come as an unbelievable relief.”