Thick As A Rain of Blows

Klaus Theweleit and the psychology of fascism.

A year or so ago there was a spate of explainer articles asking: “is Donald Trump a fascist”? The answers ranged from scholarly equivocations to frenzied rants on the impending Trumpian Third Reich. Even with the work of countless writers, theorists and academics who have studied fascism in minute historical detail, the answers to why these political movements (or specters of them) arise remain unsatisfying. A detailed study of historical documents and key figures will not reveal the reasoning of the individuals involved. “Reason,” in this case, will betray the historian, because fascism itself is a mockery of reason.

One relatively obscure scholar of fascism, in his own extremely unorthodox way, offers a compelling thesis on the persistent question of “why” fascism happens. The German writer and academic Klaus Theweleit, writing in the 1970s, suggests that fascism can be best understood through the fascists own words. He presents his argument as a kind of collage, both in form and content. His text includes hundreds of images, from vulgar Robert Crumb comic strips, to postcards and propaganda posters, to paintings, engravings and murals of nude women from all eras of art history.

The core of his text is rooted in the journals, autobiographies and novels of freikorps members, but he also borrows widely from the culture of the time, expertly using snippets of famous poems and novels from German literature, as well as the work of psychoanalysts like Freud and Wilhelm Reich, to piece together a terrifying picture of the fascist subconscious. What these texts reveal, according to Theweleit, are a kind of bizarre psychosexual politics, rooted in psychological repression, violence and, most importantly, fear of the feminine.

![]()

The experience of reading Male Fantasies, Theweleit’s two-volume text on the German, proto-fascist, freikorps militia movement between WWI and WWII, is less like hearing a professor lecture in an auditorium and more like an intimate, drunken night with a friend shouting their disappointments in your ear. First published as a 1000-page thesis at the University of Freiburg in the 1970s and translated into English about a decade later, it is a sprawling exploration of the fascist subconscious.

The central argument is this: fascist men fear women and women’s bodies and wish to destroy them. “Women’s bodies” are metaphorically represented as a kind of enormous, all-encompassing, liquid, sexual power. Femininity is a swamp, a flood, a morass, ready to envelope and drown the hard-bodied exterior shell of the “soldier-male.” This “feminine flood” is translated then to other enemies: communism, Jewishness, the chaos of the outside world and the chaos of our own psychology.

Henri Rousseau’s La guerre, 1894.

The first volume of Male Fantasies sets out to categorize women into two groups as they relate to the freikorps soldier-males.

The first group includes the “Flintenweib,” the rifle-wielding, castrating woman, whose gun-slinging (and all the Freudian phallic associations that come with said gun-slinging) poses a physical and psychic threat to the soldier-males. Also in this category are “red nurses,” women whose proximity to the battlefield, proletarian class background, unmarried status and willingness to work alongside men, represents a kind of errant feminine power.

In the second category, were “good women” or “white nurses.” These women are the “pure mother figures” and “sisters” who, because of their upper-class background, commitment to home and country, sexlessness and vulnerability, are uniquely “above any suspicion of whoring.”

This flattening and bifurcation of femininity into “good” and “evil,” “threatening” and “nonthreatening,” “red” and “white,” can also be seen in the case of the most prominent Flintenweib of our time, Hillary Clinton. Though she attempts to present herself as a “white nurse,” and indeed, wore all-white outfits during her most high profile political moments over the past election year (while accepting the democratic nomination, on the third and final presidential debate, and later, during Trump’s inauguration ceremony) she was unable to sway public reaction in her favor.

Her detractors remained repulsed by her “masculine” qualities and her “feminine” failures: her ability to achieve power and wealth, and her inability to keep her husband happy. Clinton’s sexual inadequacies are frequently referenced in the t-shirts and bumper stickers seen at Trump rallies, with slogans like “Even Bill Doesn’t Want Hillary” and “Hillary Sucks. But Not Like Monica.” In April of 2015 Trump retweeted an anti-Hillary slogan that read: “If Hillary can’t satisfy her husband what makes her think she can satisfy America?”

![]()

For Theweleit, the origins of this fear and disgust of women are also rooted in the natural world. Women’s overwhelmingly alluring destructive ability is represented in the form of bodies of water: “the enticing (or perilous) deep.” In the natural world, women are a disembodied and inhuman force, and the ocean is therefore, by extension, “the irreproachable, inexhaustible, anonymous superwhore, across whom we ourselves become anonymous and limitless, drifting along without egos.”

Alfred Böcklin’s Die Frieheit, 1891.

Similarly, history itself is presented as a flood, where masses of faceless crowds and shabby armies threaten the soldier-male with destruction. “Blood, blood, blood must flow/Thick as a rain of blows” goes one “favorite song of the fascists,” with the singer adding a phrase at the end of each verse to specify the enemy of the moment: “to hell with the freedom of the Soviet republic” or “to hell with the freedom of the Jewish republic.”

According to Theweleit, bodily excretions of all kinds, the “floods, morasses, mire, slime and pulp,” represent an unmatchable psychological power against the soldier-male, both pleasurable and unbearable. The feminine body, where the soldier male originated, is the ultimate site of horror.

Trump is a man obsessed with the horrors of women’s bodies. He has publicly called attention to the “blood” and “bleeding” of two prominent female journalists, Megyn Kelly and Mika Brzezinski. In response to Hillary Clinton arriving late to her podium during a commercial break, Trump suggested she had been using the washroom, stating: “I know where she went, it’s disgusting, I don’t want to talk about it.” What women’s bodies do is, to Trump, unspeakable. Their genitals are, like some distant landscape, located “wherever.”

The most salacious rumors surrounding Trump, involving the so-called “golden showers” videotape, seem plausible precisely because they fit into his obsession with feminine liquidity. The flip side of the fascist preoccupation with sexuality was their insistence on order, cleanliness and hygiene. In an oblique response to the “golden showers” allegations Trump proclaimed, in true fascistic form, that he was “very much a germophobe.”

![]()

Theweleit describes the military academy, an environment where the cadet learns to become hardened to external pain and is expected to exercise authority over his inferiors and accept wholly the dominance of his superiors. He argues that most men are stuck at a pre-Oedipal stage of development, still unable to reject “the mother” and fully individuate themselves. The periphery of the body remains unformed and undeveloped in these “not-yet-fully born” males, making them vulnerable to external stimulation and attack.

The soldier-male fears both its interior self –ego-less, without a sense of the “I,”– as well as its boundless exterior. On the battlefield, the soldier-male is allowed to experience the flow of desire that he so greatly fears. In this sense, Theweleit writes, “only in the act of killing or dying—penetration or explosion—can he burst his boundaries; this rule is never broken. There must be a rush of blood, either within him, or out of the other.”

Clinton herself can be seen as representing the uncontrollable, repulsive flood implied in the slogan “drain the swamp.” The fascistic impulse is to contain the flood, to “lock her up” in the steel cage of a prison cell. The most quotable highlights of the Trump camp, “grab ‘em by the pussy” included, offer perfect Theweltian summations of our current political times. The urge has remained the same, just under a century later, to contain, control, and humiliate women.

![]()

Male Fantasies leaves the reader with a warning. Our psychological needs have not changed even as historical events around us have. We still have the same desire to find freedom from ourselves, to escape from and destroy the things we fear, and to flock to those who promise us safety. In the final section of the text, Theweleit insists that “only in the most minimal sense can fascism be seen as a problem of economic development towards the end of the twenties.”

He notes: “The men they [the Nazis] addressed were the not-yet-fully-born, men who had always been left wanting; and where was the party that would offer them more? […] The word they repeatedly scream at the party congress is ‘whole’—heil, heil, heil, heil, heil—and this is precisely what the party makes them. They are no longer broken; and they will remain whole into infinity.”

Hubert Lanzinger’s Der Bannerträger (The Standard Bearer). Oil on wood, ca. 1934–36.

Male Fantasies reminds us that war has “bodily significance” that transcends the everyday political-economic system. The promise of fascism is no less than the promise of world-historical greatness, of brutal ecstasy, domination over your enemies, and the gory catharsis of the “bloody mass.” Theweleit pushes us to realize that these are desires that could lie just below the surface of any society.

Today, we remain obsessed with bodies, our own and those of others. There exist several multi-billion dollar industries dedicated to the monitoring and control of women’s bodies (the celebrity gossip industry, the weight loss industry, the cosmetic surgery industry etc.). Meanwhile, we ignore the inevitable decay of our own bodies: their clumsiness, inelegance, their foul smells, and degrading spasms.

Fascism promises transcendence from our small ugly lives, and envisions a brighter future. It promises freedom from the wretchedness of living in the world and in a body.

This is why Theweleit urges us to take seriously what may at first appear ridiculous to us. The strange language of fascism is a “language of expression” brought on by extremely common psychic wounds. He writes, “No man is forced to turn political fascist for reasons of economic devaluation or degradation. His fascism develops much earlier, from his feelings; he is a fascist from the inside.”

In other words, political issues are first and foremost rooted in psychological motivations. There is no “rational” world to escape to when the call of battle tempts frustrated men. There is no escaping ourselves.

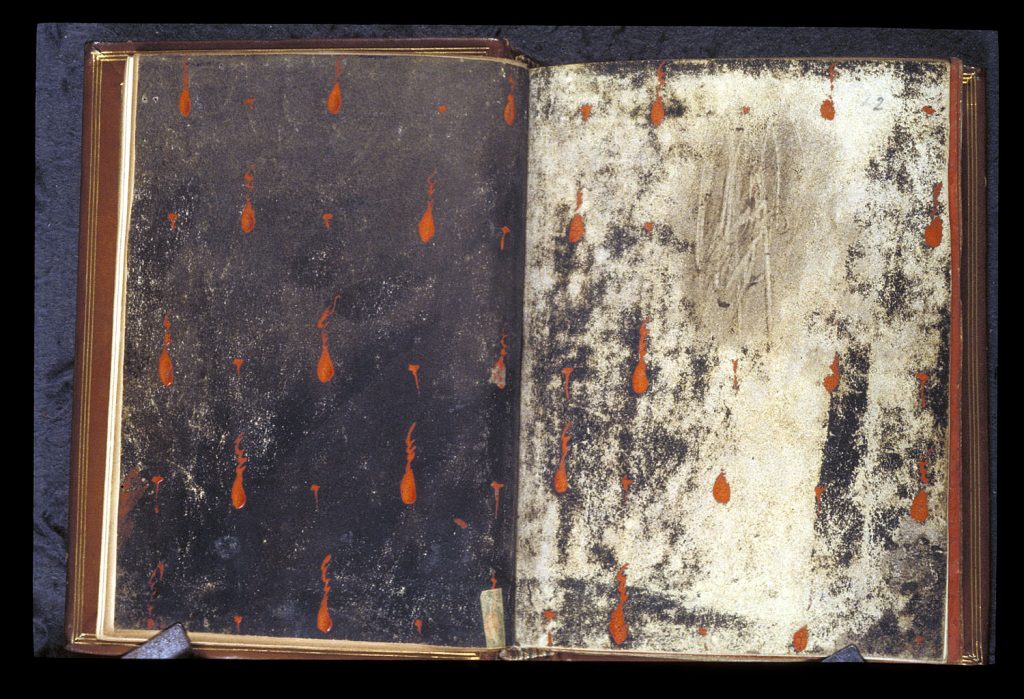

Drops of blood from BL Eg 1821, ff. 1v-2. The British Library. Public Domain.