The Curious Case of Thomas Hogg

A tragically named Puritan who stood trial for allegedly siring demonic piglets.

How Margaret Lamberton came to accuse Thomas Hogg of defiling her pig begins with a scene fit for an early David Cronenberg film. One day, during the winter of 1645-1646, Lamberton, wife to a prominent sea captain in the nascent colony of New Haven, ventured out into her property to check on the health of a pregnant sow. To her horror, she soon discovered the animal had given birth to “two monsters.” One had “fair white skin.” The other had a “head like a child’s” and a protuberant right eye. Disturbed, Lamberton summoned the town doctor for council. Before long, the pair came to a startling but inescapable conclusion: the malformed piglets looked just like Lamberton’s pig tender, Hogg. After briefly discussing the matter with the doctor, Lamberton approached town authorities, who soon arrested her servant on “suspicion of bestiality.”

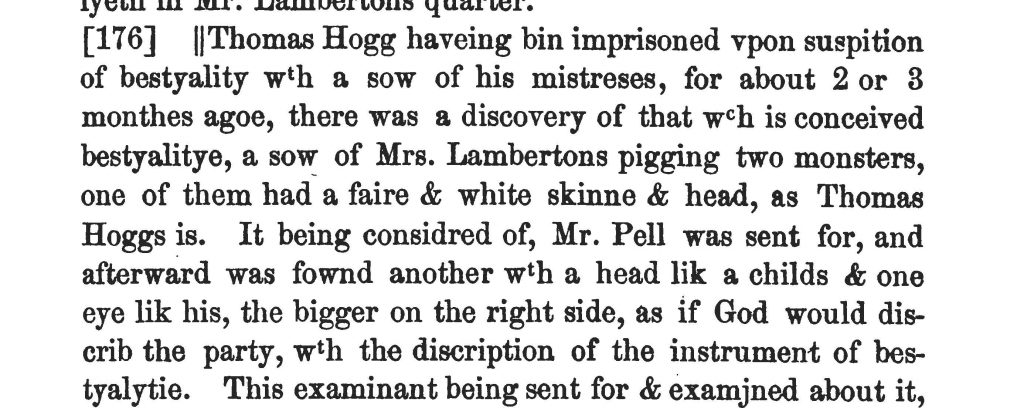

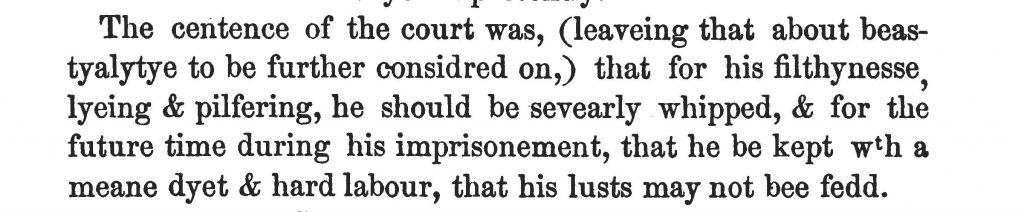

The first reference to Thomas Hogg’s arrest in a published 1857 edition of the Records of the Colony and Plantation of New Haven From 1638 to 1649.

The first reference to Thomas Hogg’s arrest in a published 1857 edition of the Records of the Colony and Plantation of New Haven From 1638 to 1649.

Marred by scientific malfeasance and biological ignorance, the ensuing investigation has for decades caused historians to titter behind collegiate lecterns. Indeed, the story has all the hallmarks of a jeer-worthy colonial yarn: bewildering superstition, mob-driven paranoia, and a painfully convoluted rationalization process, which forced town officials to reconcile rampant misbehavior in their supposedly enlightened communities.

Still, to treat the Hogg case solely as a source for derision is to sell it drastically short. Hogg, a noted town albatross, was the sort of uncouth or mildly threatening eccentric who today causes subway riders to discreetly switch cars or retreat defensively into their cellphone screens. His legal problems provide illuminating insight into how Puritans handled similarly awkward interactions with the most off-putting and bizarre of their neighbors.

Even more interesting, Hogg’s casefile demonstrates the limitations of puritanical fervor. Adherent to an unrepentantly harsh Old Testament legal system, officials in New England set low evidentiary standards for cases involving capital crimes. To justify the ugliness of this reality, and to protect their belief in the infallibility of scripture, magistrates aspired toward consistency in their application of biblical justice. Few cases better represent this phenomenon than that of Hogg, a peculiar and arguably disturbed man who had, long before Mrs. Lamberton’s accusations, tested the patience of his largely intolerant neighbors.

![]()

The official court records of the colony of New Haven are kind to few, but particularly harsh on poor Thomas Hogg. Because the accusations made against him hinged on his resemblance to piglets, court records provide a uniquely detailed account of his physical appearance. The picture they paint is less than flattering.

Resting in the middle of Hogg’s pale white head, his right eye bulged from its socket, possibly a symptom of what doctors now call Grave’s Disease. Worse, he suffered from an inguinal hernia; or, as he described it, “my belly was broake.” Born centuries before the development of corrective surgery, he wore a “steele trusse” to keep his organs from sliding through a hole in his abdominal lining. Today, we might consider Hogg a victim of a cruel chromosomal crapshoot. His contemporaries were not equipped for such sympathy. To many of his neighbors, Hogg was the living embodiment of a corporeal ugliness left over from the days of Sodom and Gomorrah—a Levitical freak capable of impregnating a pig.

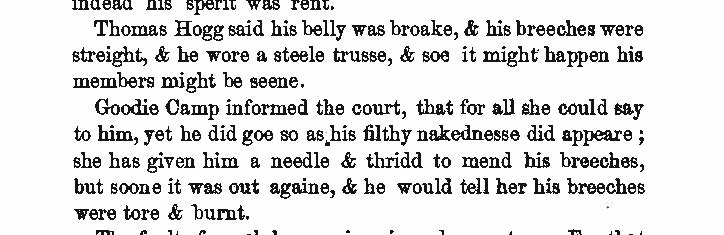

A reference to Hogg’s sartorial malfunctions. Records of the Colony and Plantation of New Haven.

Hogg was neither the first nor the last to face such charges in New England. In the 1640s, the region went through what historian John Murrin has described as “something close to a bestiality panic.” During this period, the colonies of Plymouth, New Haven, Massachusetts Bay, and Connecticut all hung at least one man for the crime. Concern about its frequency proved prominent enough in these colonies to earn multiple mentions in William Bradford’s seminal Of Plymouth Plantation. Indeed, the same journal that details the impressive array of creatures served at the “First Thanksgiving” also contains a similar but far more nefarious list: the victims of Thomas Granger, a Plymouth teenager hung in 1642 for ‘buggering’ at least “[one] mare, a cow, two goats, five sheep, two calves and a turkey.”

How colonial officials rationalized such deviancy in their protestant utopia speaks to what put Hogg in their crosshairs in the first place. According to Bradford, depraved sexual acts were not disproportionately common in New England, but rather “they are here more discovered and seen, and made publick by due serch, inquisition, and due punishment; for [the] churches look narrowly to their members…more strictly then in other places.”

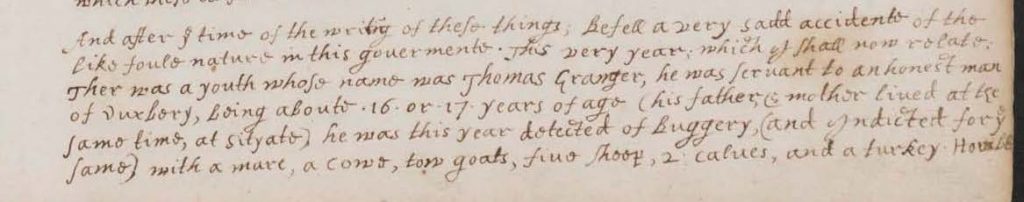

Here William Bradford, Mayflower passenger and long-time governor of Plymouth, refers to the bestiality case of Thomas Granger. Excerpt taken from a digitized copy of the original document (1630-1650), which is held by the State Library of Massachusetts.

That Hogg drew his fair share of these “narrow looks” is not surprising. His truss often tore holes in the crotch of his pants. In his own words, this meant occasionally his “members might be seen.” Mary, a co-worker of Hogg’s, had “divers times herself saw it, & told him of it, but he would deny it.” Either out of compassion or disgust, another woman named Goodie Camp had once given him “a needle & thread to mend his breeches.” Still, his pants continued to tear after an initial fix, and he seemed either indifferent or oblivious to his exposed genitals.

Ultimately, it did not matter whether Hogg had willfully exposed himself or if a personality disorder had simply short circuited his ability to feel shame. Such distinctions were not made in colonial New Haven. Hogg had become a public nuisance. In his community, this was more than embarrassing—it was dangerous.

![]() When weighing puritanical behavior, it is often difficult to discern between premeditated tribalism and subconscious prejudice. This considered, Hogg’s unflattering looks and bizarre behavior clearly placed him in an unfortunate category, which transcended taboos associated with specific crimes. “Those on the fringes of society were most vulnerable to execution,” says Lawrence Goodheart, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Connecticut and author of The Solemn Sentence of Death. Town officials hung eleven witches in New Haven—nine women, and two of the accused’s husbands. All were “socially disreputable.” Additionally, of the six men executed for rape in the colony, “five were black, at a time when African Americans were less than three percent of the population.”

When weighing puritanical behavior, it is often difficult to discern between premeditated tribalism and subconscious prejudice. This considered, Hogg’s unflattering looks and bizarre behavior clearly placed him in an unfortunate category, which transcended taboos associated with specific crimes. “Those on the fringes of society were most vulnerable to execution,” says Lawrence Goodheart, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Connecticut and author of The Solemn Sentence of Death. Town officials hung eleven witches in New Haven—nine women, and two of the accused’s husbands. All were “socially disreputable.” Additionally, of the six men executed for rape in the colony, “five were black, at a time when African Americans were less than three percent of the population.”

Hogg, of course, need not have internalized a modern understanding of “otherness” to appreciate the seriousness of his predicament. His case stood in the shadow of a direct and alarming precedent. Four years earlier, New Haven officials had executed a man named George Spencer amid uncannily similar circumstances. Spencer too suffered from physical impairments. He wore a glass eye, and, like Hogg, had a bald and unnaturally white head. When an acquaintance’s sow produced a one-eyed piglet in early 1642, Spencer’s neighbors immediately linked him to the birth. Believing a confession might save his life, he pled guilty. Officials showed him no such mercy. On April 8, they forced Spencer to watch as they ran a sword through the offending sow. Moments later, they hung him.

Unlike Spencer, Hogg refused to confess. Claiming he had not been at Lamberton’s farm when “the sow took bore,” his denial set into motion an official investigation, which culminated in yet another bizarre scene involving his employer’s devil-spawning pig.

In cases of bestiality, rape, or murder, Puritan investigators often forced defendants to confront their victims, hoping that a reenactment of the crime might catalyze a confession. At some point during Hogg’s imprisonment, the governor of New Haven, Theophilus Eaton, dragged the pig keeper from his cell and led him back to Lamberton’s property. There, they made him touch the animal that had given birth to the so-called monsters. According to Eaton, “immedyatly there appeared a working of lust in the sow, insomuch that she powred seede before them.” In need of a post-facto control group for his experiment, the governor then forced Hogg to pet another pig “as he did the former.” This animal did not respond. Afterward, even Hogg admitted how bad this had looked. Still, he remained defiant, stating “he had never had to doe with [either sow].”

Whether earnest, strategic, or deceitful, Hogg’s stubbornness ultimately saved his life.

![]() While undeniably irrational, justice in puritanical communities did adhere to certain strictures, which provided at least nominal protection for defendants. Like most theocratic inventions, these protections emerged from an honest attempt to understand and apply biblical law and mostly served to confirm preconceived notions about the purity of their divine inspiration.

While undeniably irrational, justice in puritanical communities did adhere to certain strictures, which provided at least nominal protection for defendants. Like most theocratic inventions, these protections emerged from an honest attempt to understand and apply biblical law and mostly served to confirm preconceived notions about the purity of their divine inspiration.

Town magistrates in colonial New England understood that their Iron-Age legal system often occasioned false accusations and mob-driven violence. This susceptibility directly contrasted not only their belief in the infallibility of scripture but also the precision of their own interpretation of it. This meant that in the rare occasion magistrates failed to collect enough evidence to clear the low bar they had set for execution, officials had no choice but to show leniency lest they cop to the many flaws and contradictions in their biblical sources. In doing so, they conflated consistency with justness.

In the eyes of town officials, the Bible was explicit on how to handle bestiality cases: Leviticus 20:13 demanded that “if a man has sexual relations with an animal, he shall be put to death.” The Old Testament also clearly defined the standards for execution. Numbers 35:30 stated that “no person shall be put to death on the testimony of one witness,” while Deuteronomy 19:15 further clarified that “only on the evidence of two or three witnesses shall a charge be sustained.”

Puritan courts solemnly followed these guidelines. During the bestiality trial of a teenager named John Ferris, for example, officials heard the testimony of a single witness, who claimed to have seen him “buggering” an unspecified animal (the details of this testimony were later deemed too graphic to publish in an 1858 edition of the New Haven colony records). Ferris admitted to having drawn out “his member to that purpose,” but had thought better of it and never actually committed the deed. Lacking a second witness to confirm the charges, the court sentenced him to two severe whippings and a substantial fine.

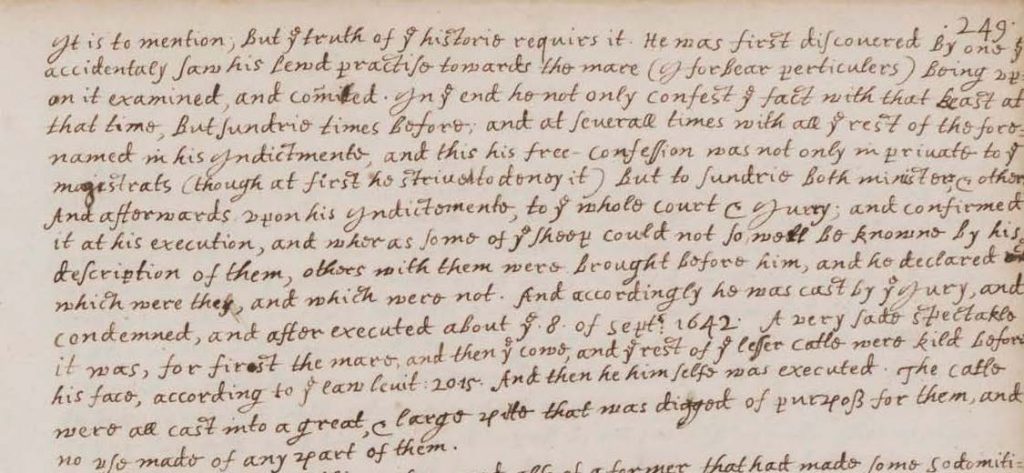

A reference to Hogg’s sentencing. Records of the Colony and Plantation of New Haven.

In Hogg’s case, no one had witnessed him with Mrs. Lamberton’s pig. Despite severe misgivings, officials had no choice but to drop the bestiality charge. They did, however, find him guilty of two separate crimes. First, citing multiple witnesses who had seen him steal food from his employer, the court convicted him of thievery. Then there was the matter of the steel truss. Enough of Hogg’s neighbors had witnessed his exposed genitals to warrant a conviction of “filthiness.” Court officials affirmed this indictment with the puritanical equivalent of a wicked burn: “He said his breeches were rent, when indeed his spirit was rent.”

Eaton sentenced Hogg to a severe whipping, a “meane dyet,” and hard labor. Though the court maintained that the bestiality charge was “to be further considered on,” it appears nothing came of this inquiry. He remained alive at least eleven years later, when officials exempted him from obligatory military training due to his “lame feete” and ever-problematic hernia.

Subsequent events would demonstrate just how fortunate Hogg was that cooler heads had prevailed. In Ferris’ trial, held a decade after his own, officials doled out one additional punishment to those listed above. As an “example of terror to others,” the court determined that “a halter be here put about his neck, which he is always to wear visibly, without hiding or putting it off.” Had the evidence raised against Hogg transcended the collective disdain of his neighbors, he may well have gone down in history as the Hester Prynne of bestiality.

Image: Kabsik Park via Flickr