Shirley Chisholm Facts

The Awl’s newsletter.

Shirley Chisholm was born Shirley St. Hill in 1924, in Brooklyn, New York, to immigrant parents.

Her father worked at a factory that made burlap bags, and as a baker’s helper; her mother was a seamstress and domestic worker. They struggled to work and care for their three daughters and decided to send them to live with their grandmother for a few years in Barbados when Shirley turned five.

Shirley lived with her grandmother in Barbados for five years before returning to New York in 1934. She spoke with a recognizable West Indian accent for the rest of her life and credited the strict, one-room school she went to in Barbados for a strong foundation for her education.

Of her grandmother: “Granny gave me strength, dignity, and love. I learned from an early age that I was somebody. I didn’t need the black revolution to tell me that.”

![]()

In 1946, Shirley graduated from Brooklyn College—she was a debate star, winning many awards—and began teaching. She went on to get a master’s degree in elementary education from Columbia.

In 1949, she married Conrad O. Chisholm, a private investigator.

Shirley became interested in politics while running a day care center in lower Manhattan in the 1950’s. She started volunteering for the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League and the League of Women Voters.

She decided to run for the New York State Assembly in 1964. She served for four years and won some important legislative victories, including extending unemployment benefits to domestic workers and sponsoring a bill to help students from disadvantaged backgrounds succeed in college.

![]()

In 1968, Shirley ran for Congress to represent New York’s 12th congressional district, Bedford-Stuyvesant. She won, becoming the first black woman to be elected to Congress.

Party leadership initially placed her on the House Forestry Committee, and, in an unheard-of move, she demanded reassignment. She was ultimately put on Veterans’ Affairs. It still wasn’t one of her first choices, but as she put it, “There are a lot more veterans in my district than trees.”

In Congress, she helped create a program to provide food to impoverished women, infants, and children (the WIC program), introduced a bill to help domestic and daycare workers get unemployment insurance, and fought for a higher minimum wage.

She eventually served on the Education and Labor Committee, becoming its third-ranking member by the time she retired.![]()

All of the staffers she hired for her office were women. Half were black women.

“Our government, if [it] indeed is a democratic form of government, must be representative of the different segments of the American society,” she said. “I feel that the cabinet and the department head of this country must have women, must have blacks, must have Indians, must have younger people, and not be completely and totally controlled constantly by white males.”![]()

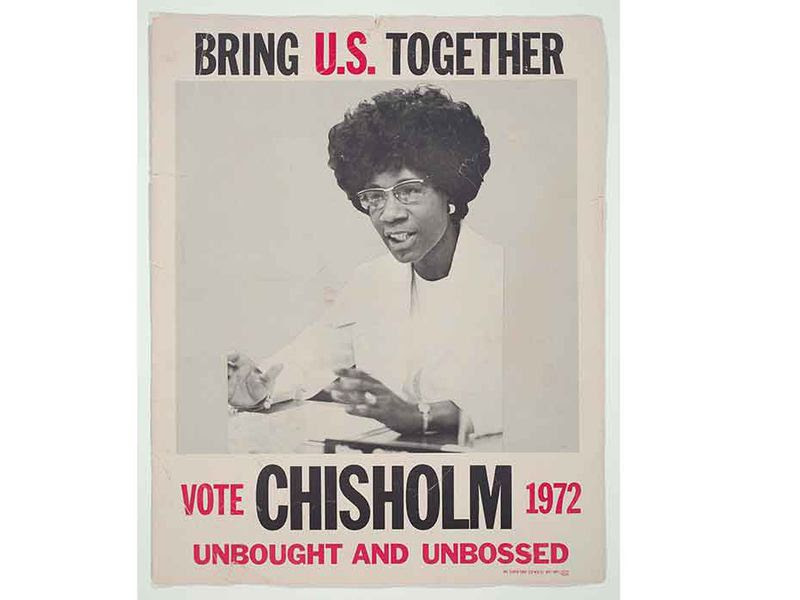

In 1972, she became the first African-American candidate to run for a major-party nomination for president and the first woman to run for the Democratic party’s nomination.

Her campaign struggled with funding (only spending $300,000 total) and with being taken seriously. There were also multiple threats made against her life. Her husband, who supported her campaign (“I have no hangups about a woman running for president”) was her bodyguard until she got Secret Service protection in May of 1972.

Her slogan was “unbought and unbossed.”![]() One of her presidential opponents, the segregationist governor George Wallace, was shot five times and paralyzed from the waist down in an assassination attempt in 1972. Chisholm surprised everyone and appalled some of her supporters by visiting him in the hospital.

One of her presidential opponents, the segregationist governor George Wallace, was shot five times and paralyzed from the waist down in an assassination attempt in 1972. Chisholm surprised everyone and appalled some of her supporters by visiting him in the hospital.

“He said, ‘What are your people going to say?’ I said, ‘I know what they are going to say. But I wouldn’t want what happened to you to happen to anyone.’ He cried and cried.”![]() Despite funding and logistical struggles, she got votes in 14 states, coming in fourth in California’s primary and third in North Carolina.

Despite funding and logistical struggles, she got votes in 14 states, coming in fourth in California’s primary and third in North Carolina.

All told she won 152 delegates, fourth place in the roll call tally and more successful than either Vice President Hubert Humphrey or Ed Muskie.

A volunteer for her campaign, Barbara Lee, is now a member of Congress.![]()

“I ran for the Presidency, despite hopeless odds, to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo,” she wrote. “The next time a woman runs, or a black, or a Jew or anyone from a group that the country is ‘not ready’ to elect to its highest office, I believe that he or she will be taken seriously from the start.”

After the presidential campaign, she returned to Congress. Over the next several years, she opposed the draft, supported increasing spending for education and health care, supported reductions in military spending, and fought for more opportunities for those in inner cities.![]()

She served seven terms, retiring in 1982 to teach politics and sociology at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. The faculty chair she held had been previously occupied by W.H. Auden and Bertrand Russell.

Shirley Chisholm died in 2005. She was 80 years old.

President Obama awarded her a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom Award in 2015. “There are people in our country’s history who don’t look left or right—they just look straight ahead. Shirley Chisholm was one of those people.”![]()

“When I die,” Shirley Chisholm said, “I want to be remembered as a woman who lived in the 20th century and who dared to be a catalyst of change. I don’t want to be remembered as the first black woman who went to Congress. And I don’t even want to be remembered as the first woman who happened to be black to make the bid for the presidency. I want to be remembered as a woman who fought for change in the 20th century. That’s what I want.”![]()

Everything Changes is an email list that changes in theme and format in every installment (usually twice a month). If you liked this email, please forward it to a friend.

Not subscribed yourself? Sign up here.