You Won't Believe These Seven Amazing Papal Elections

by Josh Fruhlinger

The Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church are gathering, right now, to start the process of electing the next pope. Exciting stuff, eh? No, not really, to be honest! What will almost certainly happen is that this group of old ecclesiastics, all of whom were chosen by one of the last two popes, will be shut up in the mildly cramped but relatively posh digs of the Apostolic Palace, and will take a few days, tops, to come to a consensus on who the next pope will be. Maybe the winner will be a surprise, and maybe the conclave will end on the first vote for once, or will extend out for a week or two. But the era of fun papal elections — and by “fun” we mean elections that were violent, weird, chaotic, overtly corrupt, or that elected more than one pope — is sadly over. We present this list as a public service to memorialize the days when papal transitions were significantly less efficiently managed.

1. Fabianus, 250: The Bird Election

In the early days of Christianity, bishops were elected through a somewhat informal process involving the clergy and parishioners of the diocese. In the mid-third century, Christianity was still illegal in the Roman Empire, and while the Bishop of Rome was considered the most important see in the Western Church, the title “pope” wasn’t yet in use, and the election was still conducted by locals. In 250, a week after the death of Anterus, the local Christian community gathered to vote, and there were several papabili among them, but, according to Eusebius of Caesaria:

Fabianus, although present, was in the mind of none. But they relate that suddenly a dove flying down lighted on his head, resembling the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Saviour in the form of a dove. Thereupon all the people, as if moved by one Divine Spirit, with all eagerness and unanimity cried out that he was worthy, and without delay they took him and placed him upon the episcopal seat.

Fabianus, whose life before this point was almost entirely unrecorded, thus became the first (and so far last) pope selected by pigeon (we can all agree that doves are basically glorified pigeons, right?). The symbolism of the Holy Ghost would of course appeal to a pious writer like Eusebius, so it seems churlish to point out that Rome had a long and entirely pagan tradition of seeking divine knowledge from the behavior of birds.

2. Boniface I/Eulalius, 418: Let’s Just Brawl This Out

By the fifth century, the Roman Empire was officially Christian and the church was an important political player, and people weren’t going to rely on the whims of birds to pick the most important Western churchman. When Pope Zosimus died, there were two rival factions within the local clergy — the deacons on one side and the priests on the other. The deacons occupied the Lateran and elected their leader, Eulalius, pope; the priests set up camp in a church in the western part of the city and elected Boniface, supposedly against his will.

Eulalius insisted on busting into town and celebrating Easter mass anyway, which set off more riots and ended up getting him arrested.

Several days of street brawls between the two popes’ followers ensued, until Symmachus, the city of Rome’s administrator, who was in his first week on the job, decided that Eulalius was the rightful pope (he had been elected first, by a day), and ordered Boniface kicked out of the city. But Boniface’s people managed to appeal to the emperor Honorius, who agreed to mediate in the dispute and ordered both candidates to stay out of Rome until the whole thing was settled. Eulalius insisted on busting into town and celebrating Easter mass anyway, which set off more riots and ended up getting him arrested. Honorius canceled the church council that was going to rule on the question and just told Boniface he was pope now, because Eulalius had been such a jerk about everything. According to the moderately sketchy Liber Pontificalis, when Boniface died a few years later, the Roman clergy asked Eulalius if maybe he wanted to be pope for real this time, but he told them to stuff it.

3. Benedict X/Nicholas II, 1059: The War Of The Would-Be Popes

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the papacy went through some rough times, during which elections were controlled by regional nobles, who often arranged for their teenage relatives/bastard children to become pope. The low point came during a stretch of the 10th century charmingly referred to as the “pornocracy” because of the popes’ sexual relations with various powerful noblewomen.

But by the 11th century, things seemed slightly improved. In 1059 Giovanni Mincius was elected pope, taking the name Benedict X. Sure, Giovanni was relative of the Count of Tusculum, the local big shot, but he was a considered a reformer! Unfortunately, the previous pope had made the Roman people swear an oath that they wouldn’t elect a new pope until Cardinal Hildebrand, the reformers’ ringleader, returned from a trip to Germany, an oath everyone was happy to forget when plied with Benedict’s family’s money. A good chunk of the cardinals left the city in a huff, met up with Hildebrand in Siena a few months later, and elected Gérard de Bourgogne, who took the name Nicholas II. Nicholas and his crew then proceeded to make actual war against Benedict’s supporters, which the former eventually won, and Benedict was thrown in jail and died there twenty years later.

In the aftermath of this unpleasantness, Nicholas promulgated the papal bull In nomine domini, which established that the cardinal-bishops are the ones who elect the pope. This theoretically cut the easily bribed lower clergy and Roman people out of the equation, and thus ensured that future elections would be based on sober consensus about what was best for the Church and its mission of spreading Christ’s good news. (Spoiler: This didn’t happen.)

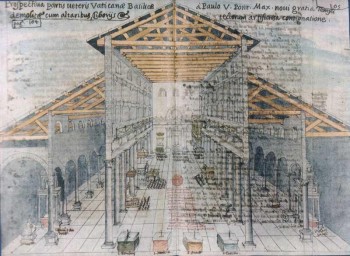

4. Gregory X, 1268–1271: The One Where They Removed The Roof

That’s not a typo: this election took three years to pick a pope. The cardinals were meeting in Viterbo, a hill town outside of Rome, and were divided into four factions — a group of Frenchmen and three mutually hostile groups of Italians — with nobody willing to give.

In late 1269, after several months during which the cardinals met only occasionally, the city magistrates rounded up them up and locked them in the papal residence there.

In late 1269, after several months during which the cardinals met only occasionally, the city magistrates rounded up them up and locked them in the papal residence there. In the summer of 1270, Cardinal John of Toledo, seeing one of his fellows praying for inspiration, quipped, “Let us uncover the room, else the Holy Ghost will never get at us”; getting wind of this, the city magistrates arranged for the roof of the meeting hall to be ripped off, exposing everybody to the elements. And yet: still no pope. The food sent into the palace was cut back to bread and water. Still no pope.

Finally, under pressure from the kings of France and Naples, the cardinals agreed to delegate decision-making power to six from among their own number — a mechanism not unlike the Congressional supercommittee that was supposed to stave of the current budget sequester. Shockingly, the dysfunctional papal conclave proved less dysfunctional than the U.S. Congress, and on November 1, 1271, the cardinals compromised and picked Teobaldo Visconti, a bishop who was off in the Holy Land with a crusading army. Visconti, who took the name Gregory X, finally reached Rome in March. Although the idea of locking the cardinals up had been a spur-of-the-moment expression of frustration on the part of the Viterban leaders, Gregory thought it was a great idea (it had, after all, resulted in his election). He promulgated the bull Ubi periculum that ordered all future elections to take place under similar circumstances, with the cardinals to be locked up cum clave, i.e. “with a key,” thus creating the institution of the papal conclave more or less as we have it today.

5. 1378, Urban VI/Clement VII: And Later, The Cardinals Went Into Hiding

There was a reason the popes spent a lot of time in little Italian towns like Viterbo: Rome, which was theoretically the capital of an Italian principality that the popes ruled, was a chaotic, ungovernable mess. In 1305, the cardinals had elected the Archbishop of Bordeaux as pope, and he decided to not bother going to Rome at all, but instead settled down in the southern French town of Avignon, because it was much more manageable and more convenient in terms of getting advice from his close personal friend the King of France. He summoned the church administrators to meet him there, and he and his successors stayed there for the next 70 years.

This grew increasingly appalling to Christendom at large and rulers who weren’t the King of France in particular; finally, in 1377, Pope Gregory XI was wooed back to Rome, in part by the stirring oratory of St. Catherine of Siena and in part to look after his political interests there. After a little more than a year, Gregory decided that, nope, the place was still a shithole, but he dropped dead before he could go back to France. In the midst of a violent thunderstorm and an equally violent mob that kept breaking into St. Peter’s and shouting, “Romano lo volemo, o al manco Italiano” (“We want a Roman, or at least an Italian,” and that actually scans sort of like “The people united will never be defeated,” so just imagine it sounded like that), the cardinals took just a day to pick Bartolomeo Prignano, who would take the name Urban VI. Prignano was not actually present, and the Roman mob thronged around the aged Cardinal Tebaldeschi, mistakenly thinking that he was the new pope, while the rest of the cardinals fled deeper into the papal palace and barricaded themselves in their quarters.

It was not hard to argue that this election had taken place under duress, and when Urban started preaching that cardinals needed to stop living in luxury and accepting salaries from various princes, most of them left town. Five months after electing Urban, they declared the papacy vacant and elected a French cardinal as a rival pope who promptly moved back to Avignon. There would be multiple mutually hostile popes for the next forty years. It was super awkward.

6. Pius VII, 1799–1800: France Spoils Things… Again

In the late 1700s, armies of the French Revolution conquered Northern Italy. By 1797 some of the revolution’s more radical anti-Catholic moves, like the attempt to turn Notre Dame Cathedral into a temple to the Cult of the Supreme Being, had flopped, but France and the church still weren’t exactly on good terms. In 1797, a general at the French ambassador’s residence in Rome tried to get a republican rally going and was shot by papal troops, which was all the excuse the French needed to invade Rome and declare it a republic, then arrest the pope and bring him back to France, where he died in custody in August of 1799.

The popes would end up using this tiara for decades because it was actually light enough to wear comfortably.

The city with the most resident cardinals outside of French control was Venice (itself under occupation by the pro-Catholic Austrians), so the fugitive church gathered there, in a monastery on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. In the face of the church’s greatest crisis in centuries, the cardinals naturally bickered for four months before finally settling on Barnaba Chiaramonti, who took the name Pius VII. With all the papal headgear having been plundered by the French army occupying Rome, Pius had to settle for a paper-mache tiara for his coronation, made in haste by the ladies of Venice and decorated with their jewels. The popes would end up using this tiara for decades because it was actually light enough to wear comfortably. Within a year, Pius had signed a treaty with Napoleon and was comfortably back in Rome and all was well that ended well, except for the part where his predecessor died in prison.

7. Pius X, 1903: “No, No, Take This Letter”

From the 1600s on, the heavy hitters of the Catholic world — the kings of France and Spain and the rulers of Austria — had occasionally exercised the right to veto candidates for pope, by telling cardinals from their realms which potential popes were unacceptable; this information would be announced to the other cardinals if it looked like the unfavored individual were about to be elected. But the practice had gradually fallen out of favor, and the last time it had been successfully used to block an election had been 1831. (The Austrians had attempted to veto the election of Pius IX in 1849, but the cardinal who had been assigned the task arrived at the conclave too late to prevent it.)

By the turn of the 20th century nobody in the College of Cardinals had given much thought to this presumably extinct institution. Nevertheless, Jan Puzyna de Kosielsko, a Polish cardinal from what was then part of Austria-Hungary, arrived at the 1904 conclave with a formal letter from Emperor Franz Joseph excluding the liberal Mariano Rampolla from consideration; after a day of voting in which Rampolla ended up in first place but short of the necessary two-thirds majority, Puzyna attempted to hand the note first to the dean of the College of Cardinals and then to the secretary of the conclave. Both of them refused to even touch it, so Puzyna ended up just reading it aloud. Everyone present reacted with horror and disgust and declared that the church could not possibly be bound by any sort of secular mandate, and yet Rampolla’s support rapidly melted away and the cardinals ended up electing a conservative a few days later. Despite the fact that the veto was responsible for his election, one of Pius X’s first acts as pope was declare that anyone who attempted to bring a veto into the conclave would be automatically excommunicated.

You might also enjoy: Roman Emperors, Up To AD 476 And Not Including Usurpers, In Order Of How Hardcore Their Deaths Were

Next week, Josh Fruhlinger wll be watching one of the no doubt many Vatican webcams, looking for white smoke. Follow him on Twitter or Tumblr. Photo of 1998 Cadillac “Popemobile” by the Hartford Guy.