DJ Johnny Dynell And The Glories Of New York's 80s Club Scene

DJ Johnny Dynell And The Glories Of New York’s 80s Club Scene

by Sean Manning

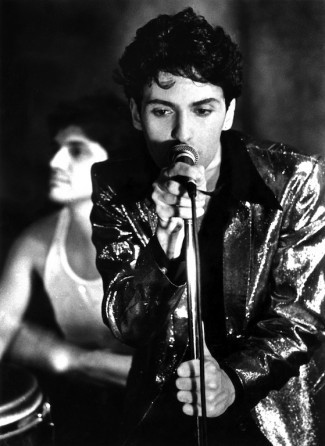

Last weekend Mark Kamins died of a heart attack at age 57. The legendary DJ and producer — who worked with David Byrne, the Beastie Boys and Sinéad O’Connor — was best known for producing Madonna’s first single, 1982’s “Everybody,” and helping sign her to Seymour Stein’s Sire Records. Around that same time, Kamins produced another popular single, the dance-rap track “Jam Hot” by Johnny Dynell. (The song was featured in the iconic 1983 graffiti documentary Style Wars, and its lyrics — “Tank Fly Boss Walk Jam Nitty Gritty/You’re listening to the boy from the big bad city” — were sampled in the #1 U.K. single “Dub Be Good To Me” by Beats International, the 1990s electronic group led by Norman Cook, a.k.a. Fatboy Slim.)

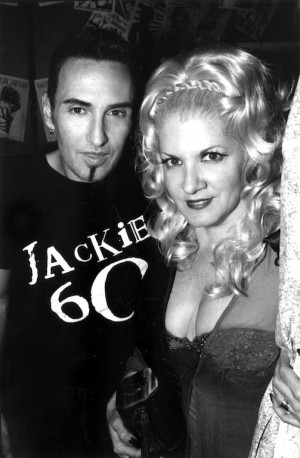

Dynell’s recording career was quickly eclipsed by his work as a DJ. For the last three decades, he’s manned the decks at every New York City club of note — Mudd Club, Danceteria, Limelight, Area, Tunnel, Palladium, Roxy, Crobar, Greenhouse, XL, Le Bain. With wife Chi Chi Valenti, he also operated the iconic clubs Jackie 60 and Mother, helping transform the Meatpacking District into a nightlife mecca. These days Dynell is as busy as ever: DJing four nights a week; providing the soundtrack to such gala events as the AMFAR Cinema Against AIDS party at the Cannes Film Festival; and organizing with Valenti for this year’s Stevie Nicks fan fest “Night of A Thousand Stevies.” We spoke over dinner at Café Orlin on St. Marks Place.

Sean Manning: Is it inappropriate to ask how old you are?

Johnny Dynell: Yes. Don’t ever tell anyone your age because they’ll treat you that way.

Where are you from?

I am from a very small town way, way up on the border of Canada. It’s upstate New York, but when people say “upstate” they usually mean Yonkers. Go to Yonkers and then keep going for like six hours. That’s Fulton, New York. It looks like Wasilla, Alaska, but not as big or as glamorous. Nothing but snow — you get, like, 13-foot snowfalls.

That’s where my parents are from but when they got married, instead of settling down they got into the car and started traveling across the country. They were party animals. I was born in Illinois while they were on the road. We would stay in one town for two weeks, then we’d go to another town. My first couple of years were spent in motels. My father did odd jobs. At one point he was photographing people’s farms out west and selling them the pictures. He would take a picture of their farms from up in the air and my mother would hand-color them. Now that I think of it, my father didn’t have a pilot license. I don’t know how he was doing that.

Did you listen to a lot of music growing up?

Yeah, my family always had music blasting. My parents listened to R&B; and blues. Etta James, James Brown — very funky kind of stuff. Especially my mother. The first records that I bought were the Jackson 5’s ABC and Sly and the Family Stone’s Stand! It’s funny, though — the first records that I bought were actually cassette tapes.

How old were you when you came to New York?

I got out of Fulton as soon as I could. I was 18. I always wanted to be in New York. I don’t know why. It was just always calling me. It’s the big city. When I was a little kid, I’d see pictures of it on TV and I just had to be there.

I came here to go to the School of Visual Arts. I didn’t have any money at all. I actually hitchhiked here. I used to do that a lot. I never had to throw myself out of a car or anything but you meet a lot of interesting people hitchhiking.

I didn’t know anybody when I got to the city and had no place to stay. Luckily, I met this girl at a bulletin board. She was just out of a mental institution and putting up a sign looking for a roommate. I moved in with her. We lived on the corner of Bleecker and MacDougal. Eventually she had a nervous breakdown and went back to Bellevue. She was very sweet, very nice, just really crazy. I felt sorry for her. People used to come in and steal her thorazine.

What did you do for money?

That whole time I was in art school I worked at different restaurants. My favorite was called FOOD. It was one of the first restaurants in Soho. Everyone who worked there or ate there was pretty much an artist or played in a band. Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth worked there, too. It was a great job and quite a scene.

At one point I worked as a waiter at the Buffalo Roadhouse in the West Village. It’s not there anymore. I was making good money as a waiter but it was just too hard. You know, being in school, playing in punk rock bands. So I traded the waiter job for one as a dishwasher there. It was a big pay cut but much easier, and I could listen to music.

You were in punk bands?

I didn’t have a musical background or play any instruments but that was the thing back then, to pick up an instrument and start an art-rock band. I was playing at CBGBs, Max’s, and in art galleries.

When you’re young and move out on your own everything is just a roll of the dice. Where you live, where you work, who you end up with, etc. When someone moves to New York, they may end up on the Upper West Side or they may end up in Brooklyn. I ended up in the East Village, Soho and Tribeca.

In those days, downtown wasn’t just a geographic location. Downtown was a way of life. It was an attitude. It meant something edgy. Now if you live in Tribeca, it means that you’re probably an entertainment lawyer. You’re probably a millionaire. I lived at Franklin and Church next to a gay black afterhours club called Buttermilk Bottom. The neighborhood was mostly artists, dancers and musicians. I was in art school and got the traditional art school education but my real education was living downtown.

I remember Ronnie Cutrone took me to the Warhol Factory once and Andy took a black marker and drew these pussies on my chest. Little vaginas. The next day in school I was studying Andy Warhol. It was weird. He was a big hero of mine and I feel so lucky to have met him.

So how did you transition from punk bands to DJing?

The DJ thing just happened by accident.

Downtown was very arty and campy, especially the punk scene. In 1980, the Mudd Club opened as a campy, funny punk alternative to uptown and Studio 54-type discos. We were making fun of them. The Mudd was a punk-rock club but it had a doorman, ropes, a mirror ball and a DJ. All tongue in cheek.

But what happened was — and people didn’t see this coming — it really took off. Every night of the week hundreds of people would line up outside the ropes hoping to be picked to get in. The Mudd Club turned into the very thing that it was making fun of. It took the disco concept into a whole new era.

I got a job as one of the DJs but it could just as easily have been as a busboy. The first night I got a bottle thrown at me. I was playing the Jacksons’ “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground).” Some punk threw a bottle at me and yelled, “Take this fucking nigger music off.” Things were in transition.

In the beginning, DJs played a lot of rock at Mudd. But punk was going out and new wave, reggae, early hip-hop was coming in. On the second floor, DJs played everything from Frank Sinatra to Chubby Checker. It was all really new and fun.

Personally I’ve always loved disco. Even when I was playing in punk bands I was also going to the Paradise Garage and the Loft.

Did DJing give you the same artistic fulfillment as the other stuff you’d been doing?

Not at first. I grew to really love DJing but in the beginning it was just a job. I was just hanging out. It wasn’t till later on that I actually learned how to DJ. But I played at all of the new wave clubs. When Nina Hagen sings, “AM/PM, Pyramid, Roxy, Mudd Club, Danceteria” in her song “New York/N.Y.”, that really was my work week! I played at them all.

When I was DJing at Danceteria, Madonna was working in the coat check. Mark Kamins, who was the main DJ there, produced and signed both of us. Her song was “Everybody” and my song was “Jam Hot.” Both songs went on the radio and were minor hits. I’ll always be grateful to Mark for that. I learned a lot from him.

What’s your all-time least favorite club?

I hated the Limelight. It gave me the creeps the minute I first walked in. It had nothing to do with [owner] Peter Gatien, who I really like. It was the place. I worked there when it first opened. I was working at Danceteria and Peter brought me over to the Limelight. He paid me, like, ten times as much money but after a week or so I just had to quit. The place just spooked me. One time Chi Chi and I went there to see a friend’s band play. Another friend, Ruth Polsky, was meeting us. A car crashed into a cab on Sixth Avenue and the cab jumped the sidewalk crushing Ruth as she was walking into the club. It was horrific. Then the whole Michael Alig mess really clinched it for me. The club had bad juju from the start.

Why did you choose the Meatpacking District as the site for Jackie 60?

We started Jackie 60 in 1990, basically so we would have a place to hang out. It wasn’t like today where a group of lawyers or investment bankers fulfill their boyhood dreams of bottles and models and open a club. It was an artist community.

Friends of ours were doing a party in the Meatpacking on Fridays called the Clit Club. It was a really cool lesbian party. There was another hot party there on Saturdays called Meat. We took Tuesdays and called her Jackie.

It was in this little place called Bar Room 432 on the corner of Washington and 14th. Where the Scoop store is now. It was just one little room with a mirror ball and clip on lights. It didn’t have anything. We put a door over two sawhorses and that was the DJ booth.

The Meatpacking District back then was edgy. It felt kind of dangerous. Meat was hanging on hooks with blood dripping down on the sidewalk. You’d literally have blood on the bottom of your shoes as you walked past the transvestite hookers into the club. Europeans loved it. Someone had a great quote. They said, “I saw more topless European royalty at Jackie 60 than I ever saw on a beach in Saint-Tropez.”

We lost money for the first nine months. We were paying performers and dancers. We were building sets, making costumes. We would do a different theme every week. I had to take on another night DJing just to pay for Jackie.

We charged five dollars to get in. At first the only people who came were artists. The public didn’t know about it. Pedro Almodóvar would bring like 20 people. Julian Schnabel, Pat Field, Alba Clemente — they would all bring people and they would all pay. That got us through the early days. Then Jackie 60 exploded. The first night that we got busy Debbie Harry jumped behind the bar and started bartending. People were stunned. They don’t know Debbie.

Jackie became very fashionable. Marc Jacobs, who was an original Jackie 60 member, was soon followed by supermodels and other famous designers. Once those people are there carrying on — Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, and Calvin Klein, crawling across the floor at 5 a.m. — you start getting Page Sixes and the masses. We needed a door policy.

The door policy was severe but very simple. It wasn’t about how much money you had or were going to spend. You just had to add to the party. When you walked up to the door, Kitty Boots would look at you and think, “What is this person going to add to the party?” For instance, if she lets in some rich old man, you know she’s going to let in some cute 17-year-old hustler knowing that they will work it out. We used to say, “For every cup there’s a saucer.” Jackie 60 was like Noah’s Ark, two of everything.

What do you think of DJs today — David Guetta, Deadmau5, etc.?

DJing has changed so much. When I first started, there were like a hundred DJs. You knew everybody. Now there are a hundred DJs in my building! Every kid over the age of 14 is a DJ. They put DJ in front of their name on Facebook, get Serato, and think that they’re a DJ. It used to take technical skill to mix records. Now there’s a “Synch Button” that you push and it blends the two songs together. I’m sorry, that’s not DJing.

Guys like David Guetta — they’re pop stars. They’re not really club DJs. They do 45-minute sets that are basically video and light shows. They do these cheesy DJ moves like pump their fist in the air and the kids go crazy. If you ever see a picture of these guys DJing, they always have one fist in the air and the other hand is on… On what? What is it doing? Hitting synch?

I do like Deadmau5. I think he’s a very smart guy. I’ve played with him a couple times. I know a lot of people think that the mouse-head thing is just a gimmick but I like what he does. To me, he’s creating this living Dadaesque avatar. I see him as a performance artist. Plus, he’s a bad-ass DJ and producer.

What do you think of New York’s current club scene?

There are some great new house music parties going on now. Parties like Spank, Wrecked, Bassment, ElevenEleven, and Westgay all have that old Jackie feeling. I love it. For a while it was just all about bottle bars. Thank God that’s over!

What’s the one song, no matter the crowd or venue, that never fails to get people on the dance floor?

Cheryl Lynn’s “To Be Real.” White people like it, black people like it. The Paradise Garage crowd would like it, the coolest Brooklyn hipster crowd would like it. It works right across the board.

Previously In New York Q&As;: A Q&A; With Editta Sherman, Celebrity Photographer, Age 100

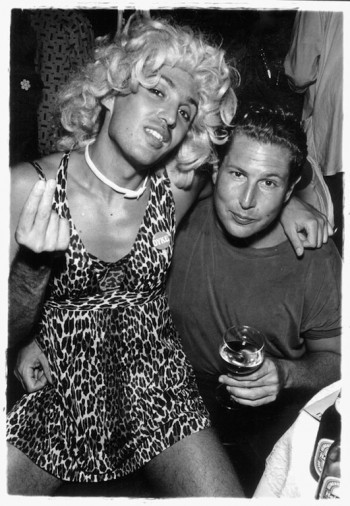

Sean Manning is the author of the memoir The Things That Need Doing and editor of several nonfiction anthologies, most recently Bound to Last: 30 Writers on Their Most Cherished Book. He also edits the blog Talking Covers. From top: 1986 photo of Dynell with Julian Schnabel at the Palladium by Wolfgang Wesener; 1983 photo of Dynell performing “Jam Hot” at Danceteria by Chris Savas; photo of Dynell with Chi Chi Valenti at Jackie 60 by Paul Brissman; bottom photo by Sean Manning.