What Made "The O.C." Great, Bitch

What Made “The O.C.” Great, Bitch

by Jia Tolentino and Mallory Ortberg

“Welcome to the O.C., bitch.”

— Luke, “The O.C.,” Season 1, Episode 1

Sometimes disorder introduces itself into long-standing order. Such is the plot of almost everything compelling: “Downton Abbey,” the evolution of the norovirus, “The Nanny,” bedbugs, “Jurassic Park,” civil rights, the lineup changes of Foreigner, infidelity. So goes, also, the story of Ryan Atwood, who storms Newport’s gated communities with little more than a hoodie, a wrist cuff, a pack of Marlboros and his trademark Chino flair in the pilot episode of “The O.C.”

This essay is part of a series about our favorite TV shows past.

Previously: The Joys And Derangement Of “F Troop”

We, perhaps you, and millions of other people of a certain emotional archetype were devoted to “The O.C.” We huddled in front of the TV on Tuesday nights with bottles of Boone’s Farm and a near-religious fervor. We gasped when Ryan carried Marissa’s prone body through the streets of Tijuana (“Tee-hauna,” Seth would clarify). We have the orange-and-blue DVD box sets and we will never throw them away no matter how impractical DVDs become. We have described our relationship with the show’s first season as both “incredibly, unhealthily obsessive” and also “the best I’ve ever had.”

“It’s personal in the deepest possible way,” said Ira Glass of his weekly ritual surrounding “The O.C.” “I’m 47 years old. I’m a grown-ass man, you know? We’re a married couple. Sober. We are sober, singing the theme to a FOX show. And I have got to say, every single week it makes me love my wife, and love TV, and love everything in the world all at once. And last week, when ‘The O.C.’ went off TV, I cried. And I’m not ashamed to admit it.”

The show’s fanbase watched so attentively that, years later, IMDB still lists continuity errors like “When Haley is seen at the club dancing, her hair is curled. When she’s leaving the club her hair is straightened” (Season 1, Episode 22, “The L.A.”). At UC Berkeley, Peter Gallagher’s role on the show has been immortalized by the Sandy Cohen Public Defender Fellowship, which supports law students working in the Orange County public defender’s office. This is something that exists in real life.

A decade after its first season originally aired, “The O.C.” seems both prescient and profoundly of its era. In some ways it’s a time capsule of American culture in 2003 — Paris Hilton appears as a not-exactly-ironic-but-decidedly-self-referential UCLA-attending version of herself who begs Seth: “Don’t tell anyone I’m a grad student, okay?” — but in other ways, the show was groundbreaking. It was the first show to capitalize on the growing popular appetite for indie music, an early champion of nerd culture as default, the first teen soap to be explicitly self-aware. It had a parody of itself (the TV show “The Valley”) nested within its universe. The show prompted a resurgence of a golden, West Coast exceptionalist fantasy whose pop-culture descendants have been both regrettable (“The Real Housewives,” “The Hills”) and terrific (SNL’s “The Californians,” The Lonely Island’s “The Bu”).

***

For those who have never seen “The O.C.”: a word.

The ostensible protagonist was Ryan Atwood, a brooding Russell Crowe-lookalike who, when the series begins, is in jail, sitting down with a giant-eyebrowed public defender named Sandy Cohen. Sandy was married to workaholic ice queen Kirsten, whose father Caleb is a real estate mogul who “owns half of Newport.” The Cohens’ teenage son Seth — picture a young, male, Jewish Liz Lemon, who acts as an audience stand-in and is the real star of the show — becomes Ryan’s best friend and confidante when the Cohens decide to install Ryan in their pool house, giving him a shot at a better life.

What this better life looks like for Ryan: a beautiful blonde named Marissa Cooper, the girl next door with sad deer-eyes and prominent collarbones. Marissa’s best friend Summer, a travel-sized brunette, has for years been the object of Seth’s lifelong unrequited love. Marissa is a secret populist and budding substance abuser whose father is about to commit Madoff-style fraud. Marissa’s mother wears Juicy tracksuits and acts as a fierce guardian of her own class anxiety and across-the-tracks background. Marissa’s boyfriend Luke is an evil lacrosse stick dipped in grain alcohol (the grain alcohol is also evil).

These ten characters, spanning three generations, meet in six different romantic combinations within the first season. The pilot episode of the show alone covers grand theft auto, cocaine, juvie, white-collar fraud, a seven-figure wealth gap, a threesome in the bathroom of a high school party, brawling, infidelity, alcoholism. Yet the great trick of the show is that it doesn’t feel like all that. It feels private, like a diary. It took melodrama and removed the self-importance. It used its carefully engineered exterior of beauty, wealth and scandal to sneak in an interior that was all depth and familiarity and heart.

***

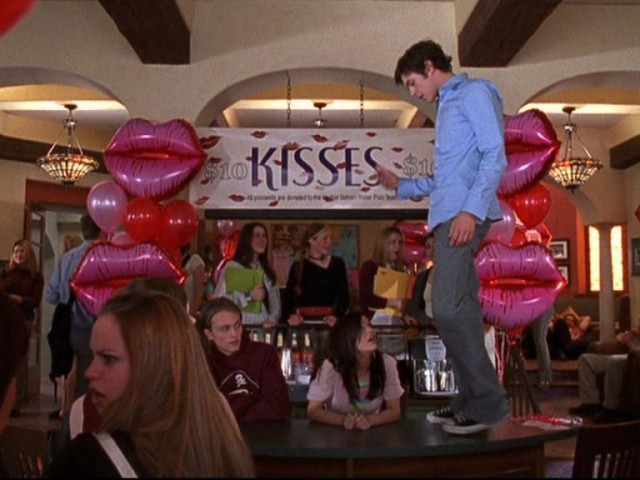

The appeal of “The O.C.” begins (and for some, ends) with the official soundtrack, a billion-footed indie beast that Josh Schwartz, the show’s creator, set out to make into a character in its own right. Episodes were often soundtracked before they were scripted. Up-and-coming artists premiered their new songs on “The O.C.” and often performed on the show’s concert venue The Bait Shop. The audience in turn paid close attention to who was on the roster; when one episode featured the U2 single “Sometimes You Can’t Make It On Your Own,” the reaction was fierce. “Selling out,” wrote an Entertainment Weekly columnist, presumably with a straight face. Musically, the show had pulled off a gambit that has since become commonplace; the soundtrack was nominally indie but undeniably popular — stylized and edgy enough for viewers to feel addressed as unique individuals, but approachable and mainstream enough to draw the crowds.

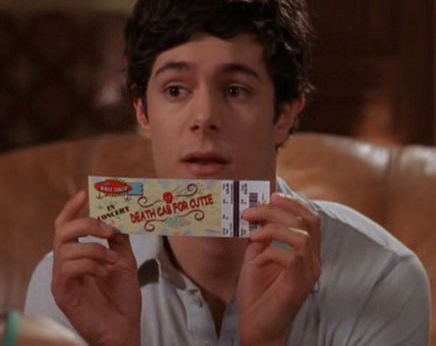

If you compare the music of “The O.C.” to other shows of its era, it starts to seem even more remarkable. “Dawson’s Creek” ended the same year that “The O.C.” began, but the two seem generations apart. Dawson’s was all plunky guitar and Alanis Morissette playing over soft-focus, flannel-ridden montages. The same year, “The O.C.” featured Röyksopp, LCD Soundsystem, The Pixies, and Tunng, as well as many artists that defined the wave of gloriously sincere early-2000s indie chart-toppers: Feist, Death Cab for Cutie, Wilco, Sufjan Stevens.

Indie-as-middlebrow is standard today, and the “The O.C.” doubtlessly played a part in this model’s genesis. Were it not for the show, Stephenie Meyer — the most visible force of lowest-common-denominator culture in recent memory — might not now be urging her blog readers to listen to Grizzly Bear and Animal Collective.

***

“The O.C.” drew heavily on one of the most important soap opera conventions: that of erasure, where consequences are few and often impermanent. In the first season of the show, Julie Cooper appears to be happily married, a picture-perfect trophy wife. But by the fifth episode, Julie has filed for divorce; by the tenth, she’s dating Kirsten’s father. Then, in episode 19, she begins an affair with Luke, her daughter’s ex-boyfriend. A few episodes later, Luke is gone and Julie’s back with Caleb; the season closes on their wedding and a “Hallelujah” cover.

Luke, who resembled nothing more than a poor man’s Casper Van Dien, spent the first season undergoing more character rewrites than anyone else in television history. In the pilot he is a featureless goon in a puka shell necklace, the empty swagger of Newport Beach writ large (“Welcome to the O.C., bitch” is quite rightly the most memorable line from the show, even though Luke is one of its least memorable characters). By the end of episode two, he has displayed a glimmer of self-reflection and at least attempted to save Ryan from a burning model home. By episode seven, he is an unfaithful sociopath, whose public infidelity is largely responsible for Marissa’s overdose. From there he confronts his own homophobia after learning his father is gay and in love with another man, sleeps with Marissa’s mother Julie, saves Marissa from the wily Oliver, repairs his friendship with the gang, and picks up a guitar and starts dispensing soulful advice. He closes his character arc with perfect equanimity, joking that he’ll fall in love with a Portland girl and have to fight her football-captain boyfriend, and will end up on the receiving end of a sucker punch and a “Welcome to Portland, bitch.” What other teen drama displayed such self-awareness?

Luke pulls off the ultimate teen dream of self-transformation: he remakes his identity easily and totally, whenever it suits his needs. In the early days of the series, Luke could not make it through a school day without hitting someone; by the time he decamps for Portland, friendly Gay Dad in tow, he practically presses his palms together and murmurs “namaste” at every goodbye. Everything in the world happens to Luke. Nothing does not happen to him. He contains multitudes.

***

The syllabus for Duke University’s course on “The O.C.”, titled “California Here We Come: The O.C. and the Self-Aware Culture of 21st-Century America,” begins with a quote from Schwartz: “Everybody is hyper self-aware. We live in a post-everything universe.”

This “hyper self-awareness” may be what “The O.C.” was best at, its desire to stay one ironic step ahead of everything communicated most clearly through one character, the (as described on the Duke syllabus) “nerdy, comic-book reading, plastic-horse-loving, half-Jewish sailor with a keen taste in music named Seth Ezekiel Cohen.” With his comic books and Michael Chabon novels in hand, Seth was the reliable, deflationary voice of reason. “You’re a Cohen now. Welcome to a life of insecurity and paralyzing self-doubt,” he says to Ryan early in the first season. Throughout the show, he does not become more like the other characters, but they become like him, even adopting his hyper-fast and ultra-quirky speech patterns.

Everything that could be criticized about “The O.C.” was addressed outright on the show. Benjamin McKenzie, the actor who played Ryan, was frequently called out for looking much older than a teenager; in one episode, Ryan sees the actor who plays his equivalent on a teen soap called “The Valley,” and asks, “How does that guy play a high schooler?” Seth sighs. “Hollywood,” he says.

As the show progressed, the characters continued voicing their own audience. “I wish I was from the Valley,” whines Summer in one episode. “Ugh, they’re playing Death Cab on ‘The Valley’?” says Marissa’s little sister, Kaitlin, in another. “I’m never listening to them again.”

The show even addressed its own impending decline in the first holiday episode. “What if it’s starting,” asks a worried Seth. “The Chrismukkah backlash. What if it’s getting too big and commercial. Dude, I knew this would happen, it’s like it starts out as this really cool cult holiday, you know, flying beneath the cultural radar, then suddenly it crosses over and there’s too much pressure.”

In the second season, Marissa embarked on a short-lived lesbian relationship with rebellious club manager Alex Kelly (played by popular fictional lesbian Olivia Wilde) during Sweeps Week. “Hey listen, Alex,” Seth tells her when he realizes the two of them are dating. “Thank you. Both of you. For everything. I mean, keep doing what you’re doing. I like it.”

***

No other show ascended as high or crashed as hard as “The O.C.” When it started airing, it had the highest ratings among 18- to 34-year-olds of any drama on television. The first season was incandescent; the second was wildly uneven (the arrival of Caleb’s secret daughter,Kirsten’s alcoholism, Marissa’s poolside meltdown). But the rest of the show was abysmal and heartless — quick shouts to Taylor Townsend and Trailer Park Julie Cooper, though — and by the time it went off the air in 2007, it had been abandoned by nearly all of its former fanatics.

So what happened? Maybe “The O.C.” exhausted the big formulas too quickly; in the classical models of comedy and tragedy, the first season ended with a wedding and the second with a death. Maybe, as with “Gossip Girl,” it became impossible for the writers to maintain depth for too long in a setting that was defined by its superficiality. Maybe, as with “Downton Abbey,” the initial plot — the outsider becoming the insider, winning hearts, establishing a new and better order — was the only one that carried real urgency.

But probably the real answer is that the show just lost its heart. It happens to most shows. It happens to most things. The relationship a certain kind of young person had with “The O.C.” while it lasted was exactly like most of our first relationships, full stop: obsessive, full-throated, and often unrequited. It didn’t matter whether your ardor was returned; that person that inspired spirals of conjecture, song lyrics mapped out painstakingly to every twist and turn of behavior. The person was everything, but once you parted ways, you never thought about him or her again.

Previously: The Joys And Derangement Of “F-Troop”

Jia Tolentino lives in Ann Arbor. Mallory Ortberg is a writer in the Bay Area. Her work has also appeared on The Hairpin, Slacktory and Ecosalon.