The Lost Art Of Opium Smoking: An Interview With Author Steven Martin

by Abe Sauer

Of all it has embraced, the booming artisanal movement has so far passed over one largely extinct 19th-century practice: opium smoking in the old manner.

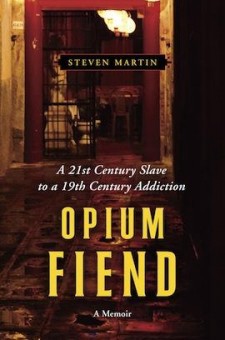

But in a book out last year, one collector of antique opium-smoking paraphernalia documents how his fascination with a lost era’s artifacts led to an attempt to recreate and live in a lost era of chandu, resulting in an opium addiction of “the traditional manner” that reached a peak of thirty pipes a day. I spoke with author Steven Martin about his book, Opium Fiend: A 21st Century Slave to a 19th Century Addiction, his Opium Museum project, and the cultural legacy of a practice that went from one of the world’s most popular to practically nonexistent in a matter of a few decades.

Abe Sauer: In the book you state that you “wanted an exotic life.” While such quests for “an exotic life amongst the noble savagery of Southeast Asia” drives the backpacker circuit, you careened off the normal Koh Samui Moon Party opium-dabbler path. Why?

Steven Martin: The old “opium-dabbler path” was found up in the mountains, among the tribal peoples of northern Thailand and Laos. I seriously doubt anyone was doing opium at the Koh Phangan “Full Moon Parties”, but Western backpackers into partying no doubt made it a point to check out both venues. I myself wasn’t in Southeast Asia on the backpacker circuit. I’d been living there full-time since completing a four-year stint in the U.S. Navy in the 1980s. As I explain in Opium Fiend, I noticed the backpacker interest in opium smoking while working on updating guidebooks to Laos.

Opium smoking in the traditional Chinese manner had almost gone the way of the dinosaur in Southeast Asia — Laos was the last country in the region where a handful of rustic opium dens survived. But then the backpackers discovered them and made it profitable for poverty-stricken local addicts to open dens for the visitors — and these makeshift operations mushroomed along Laos’ backpacker trail. I passed word of the situation along to a journalist friend who was working for the Asian edition of Time, and he flew out from Hong Kong to do a story, hiring me as a translator and a fixer for the research phase. We spent some time in Vientiane, the capital of Laos, and it was there that I had what I like to call a “collector’s epiphany” and got the idea to start collecting antique opium-smoking paraphernalia. That’s how my big opium adventure began.

Abe: Your desire for the “exotic life” appears to not only have included geography but also the romantic aesthetics of the practice. For example, you tell of having a linen suit replica of the one worn by Tony Leung in The Lover.

Steven: The tropical linen suit was a direct offshoot of my opium smoking — I wanted to experience the vice exactly as it had been practiced in the old days. At first I put all my attention to gathering the correct paraphernalia. Once I’d accomplished that, I began to work on my surroundings and apparel. Me and an opium-smoking friend put thousands of dollars into recreating a 19th-century opium den, and whenever we smoked there we’d dress in period clothing to get the right atmosphere. Years later, when I found myself addicted to the drug, I began smoking alone and on a daily basis. But I never lost track of the fact that what I was doing was extraordinarily rare, and I used to get dressed up every Saturday — wearing my linen suit while reclining on the opium mat — as a way to remind myself to treat the old ritual with deference and formality.

Abe: Films that romanticize the opium smoking period feature in your story in a number of instances. But another you mention, a less than romantic film, is Apocalypse Now. Alex Garland’s 1997 book The Beach was also fascinated not only with this film, but the whole post-war, 1980s Hollywood Vietnam catalogue. You cite Now as a film that got you interested in Asia travel, just like the Beach protagonist. What gives?

Steven: I’ve never read The Beach, and I don’t know anything about it except that it’s a novel and was made into a movie that was filmed in Thailand. My first viewing of Apocalypse Now in 1980 was partly what inspired me to make my first trip to Southeast Asia — more specifically to the Philippines, where Apocalypse Now was filmed. I made that trip in 1981, a few months short of my nineteenth birthday. While I was in Manila I did a day trip to Laguna province where you could hire a canoe up the Pagsanjan River, where Marlon Brando’s commander-gone-mad scenes were filmed just a few years before. The jungle scenery was spectacular but by that time most of the film’s sets had already been destroyed or taken apart by scavengers.

Abe: Speaking of movies, a common complaint in the book is that so many films incorrectly portray opium smoking. During one smoking session, you fantasize about tutoring Johnny Depp “in the fine art of rolling” after seeing “his botched performance in the opening scenes in the film From Hell. Yet, you very recently had an experience with a film production studio that balked at spending a mere $600 to hire you and your collection to get it right. Why does it matter that audiences see this accurately portrayed?

Imagine somebody soaking a dried tobacco leaf in hot water and then drinking the result in hopes of replicating the experience of smoking a fine Cuban cigar.

Steven: I think an accurate portrayal adds credibility to a performance. Of course there aren’t too many people who will know whether or not an opium smoking scene is portrayed accurately, but myself and a handful of other collectors will.

The film you mentioned in your question will be based on a 1926 memoir by the pseudonymous Jack Black, a career criminal who operated in the western United States and Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Black was an opium smoker, and so the props master got in touch with me through my website and asked about hiring me to consult. The props guy and I went back and forth for weeks, and because apparently the film was on a very tight budget, I offered to consult for $600 — almost nothing — because I was interested in the film’s subject matter and helping them get it right. And you know what? They turned me down. Six hundred bucks was too much to get a key element of Jack Black’s character right. But this is how producers and directors think. They’re gambling, rightfully perhaps, that their audiences will be just as clueless about opium smoking and its paraphernalia as they are.

Abe: Meanwhile, “Boardwalk Empire” did enlist your services. Why?

Steven: Martin Scorsese was the executive producer of the episode that I consulted for, and I understand he’s a stickler for historical accuracy. The opium-smoking scene was part of a montage at the end of Episode 5 in the first season. I think it says a lot about the quality of “Boardwalk Empire” as a whole that they would fly me from Los Angeles to New York and put me up in a hotel in Manhattan — not to mention renting authentic paraphernalia and paying me for a day’s work — all in order to get right a scene that lasted no more than a couple of minutes. But then, anyone who has watched the series will agree that the writing and research are nearly flawless.

Abe: One of the common images of the opium smoker is one of smacked-out, paralytic, horizontal destitution. Yet many smoked for recreation only.

Steven: The reasons for that stereotype are manifold, and, as with all stereotypes, they’re partly based on fact and partly on misunderstanding. During the heyday of the opium trade, raw opium exported by the British from India to China was purchased by Chinese brokers who then repackaged the product for sale to opium smokers within China. These brokers processed the raw opium into smoking opium, or chandu, and during this process they added impurities — the most common being opium ash — in the same way that drug cartels add nonessential ingredients to pure cocaine or heroin in order to boost their profits. Opium ash has a high morphine content, and adding it to pure opium not only increased the quantity of the product, it also made the high more numbing. So people with limited means who smoked low-quality opium cut with opium ash were more likely to lie around in a daze. And these were exactly the kind of smokers most often witnessed by Westerners living or traveling in China.

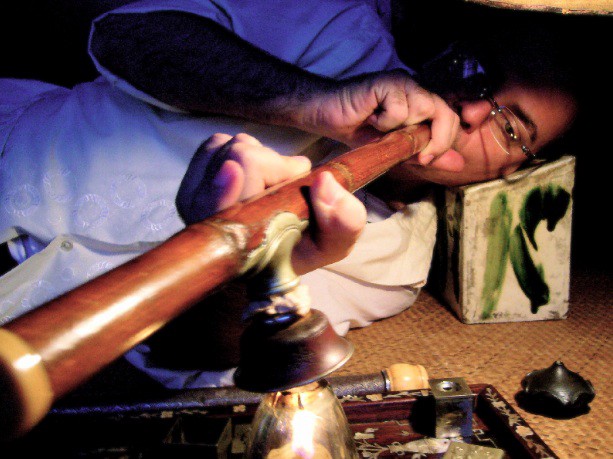

Another reason for the stereotype was the design of the Chinese opium pipe, which used an oil lamp as a heating source to vaporize the opium. The only comfortable way to hold the opium pipe over the lamp and monitor the drug as it vaporized was to lie down. However, pure, good quality chandu smoked in moderation was energizing, both physically and mentally. So the effects really depended a lot on the kind of opium being smoked.

Abe: And you argue that opium is no more harmful — and maybe less so — than alcohol.

The only comfortable way to hold the opium pipe over the lamp and monitor the drug as it vaporized was to lie down. However, pure, good quality chandu smoked in moderation was energizing, both physically and mentally.

Steven: No, not quite. Except for the very first chapter of Opium Fiend, my story is told chronologically and so my opinions and observations in each chapter reflect what I was thinking at the time. What I wrote was that during the time I was addicted to smoking high-quality opium, I felt that the habit was physically less harmful to the body than alcoholism. I also noted that my beliefs mirrored the opinions of H.H. Kane, a New York doctor who studied opium smoking in the dens of Manhattan in the 1870s and 1880s. But my views about the relative harmlessness of opium evolved as I got deeper into the habit and experienced how excruciatingly difficult it was to stop.

Abe: Opium “pipes” are still largely misidentified on “collection” sites and eBay. But from time to time one shows up for sale. How much work would it be for a person to assemble a working, traditional smoking kit?

Steven: That depends on how complete a layout we’re talking about. But even at its most basic, finding components that are functional might take years — especially for an amateur. These are antiques a century or more old, and even in pristine condition, they would need repairs to make them functional. And despite what I’ve done in the past, I think it’s wrong for someone who doesn’t know what he’s doing to make modifications to a rare antique just to try to get a buzz. I’ve seen pipes that should have been in museums damaged beyond repair by amateur collectors hoping to have some amazing opium experience. The only thing that bothers me more is the damage that antiques dealers do to old opium pipes and lamps by embellishing them in hopes of reselling at a high price.

Abe: One of the more interesting points you make in the book is about the popular, but historically distorted narrative that imperial powers foisted opium on the unknowing Chinese. China in fact perfected the practice and imperial powers, like the British, only made it cheap and accessible. Why does this narrative persist?

Steven: One of my theories is that if it weren’t for the Chinese invention of the specialized pipe and lamp that made it possible for opium to be enjoyed recreationally, the British opium trade might not have happened at all. It certainly wouldn’t have been the moneymaker that it was. I’m no apologist for the British opium trade, but history is seldom black and white, and in my opinion history is much more interesting when it’s remembered and passed on with its contradictions intact. Why does this erroneous historical narrative persist? For the same reason they usually do: Painting itself as a pure and simple victim is strong political propaganda for one side (China), while the other side, the one that’s most to blame (Britain and other Western colonial powers), has no stomach for pointing out otherwise.

Abe: It was recently reported that opium cultivation is booming thanks to a spike in demand for heroin in China, where users have quadrupled in the last decade. (Meth use is also way up.) But the practice still seems almost nonexistent, though, recently, a Chinese official was charged with corruption and smoking opium “to keep up with late-night barbecue parties.” And while the word is still somewhat taboo in China, concern about the rebirth of the practice seems so tangential that state censors recently allowed a Chinese film (Wong Karwai’s The Grandmasters) to feature an opium smoking scene. Can opium smoking ever “come back?”

Steven: For a number of reasons, I seriously doubt opium smoking in the traditional Chinese manner will ever come back. For one thing, despite its having all but disappeared, regulations against opium smoking are still on the books just about everywhere. But another major reason is the difficulty involved in smoking opium — or, more correctly, vaporizing opium — in the traditional way. You need chandu, opium specially processed for vaporizing, and you need a set of this very specific and distinctive paraphernalia, and it has to be in working order. And once you have all that, you need somebody who can teach you how to use it.

I think anyone nowadays who happened to get hold of some raw opium would probably end up mixing it in their tea — but that’s just not the same thing. Not even close. Imagine somebody soaking a dried tobacco leaf in hot water and then drinking the result in hopes of replicating the experience of smoking a fine Cuban cigar. That’s what drinking opium tea is compared to vaporizing opium with the proper accoutrements.

And besides all that, people nowadays want instant gratification. Opium smoking is slow and old fashioned. I get the feeling that a lot of people are curious and would try it once if it were available to them, but how many would be obsessed enough to go to the extremes that I did in order to pick up an old-time opium habit? Very few, I reckon.

Abe: What advice would you have for somebody who read your book and, ironically, “wanted an exotic life” that included opium?

Steven: Good luck!

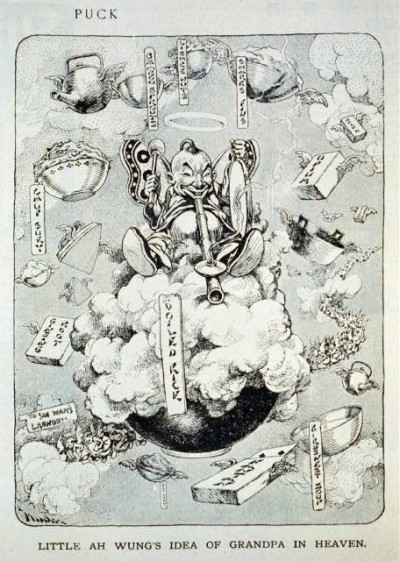

Abe Sauer is the author of How to be: NORTH DAKOTA. Photo of the author smoking opium; credit: Jack Barton. Illustration from the Library of Congress collection.