What Was the Suzuki Violin Method?

Teaching tiny people to play music.

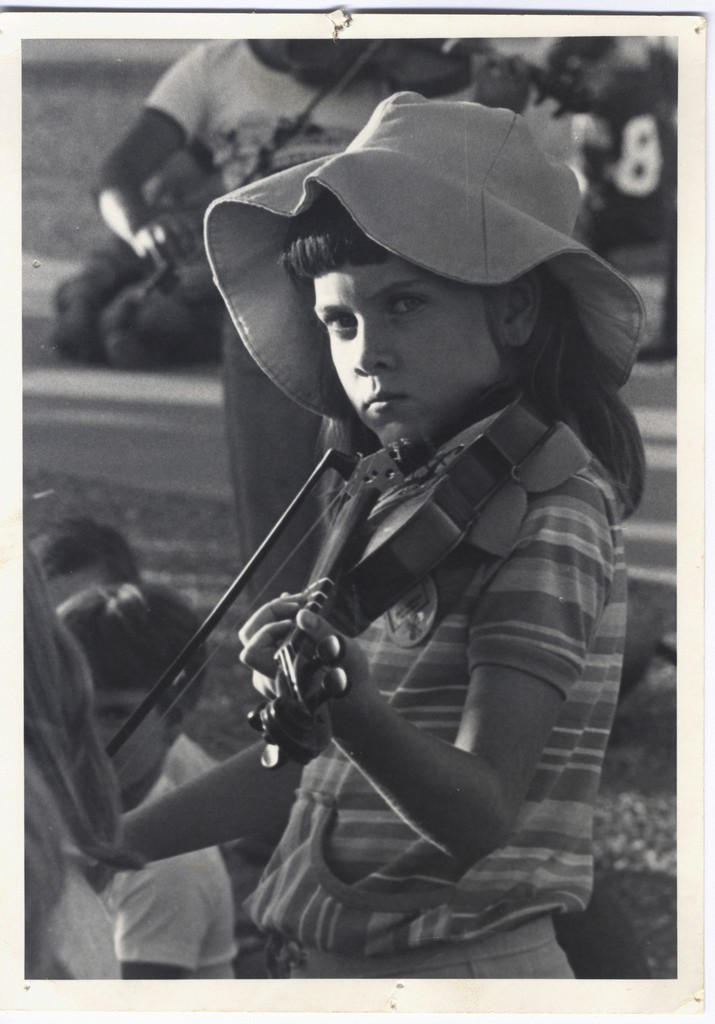

In a house at the edge of a long and narrow river, I am crying. I am three years old, anxious to play the first notes on the tiniest of violins available, as a woman in a long dress instructs me to lift the instrument from the space beneath my elbow, hold it tightly between my neck and chin, and gently cross the strings with my bow. I know the violin; long before I am ever allowed to hold the instrument, I watch as men in tuxedos shimmer under lights at the symphony, as women in the lobby kneel with the smallest of passersby, allowing young children to closely inspect their instruments as they describe the make and function of each body’s parts. More than anything, I want to stand before an audience, to strike each sound with its own careful resonance and put forth the sum total of a cumulative tradition of presence. Through pursed lips, I steady my wrist, ease the reeded shape through my shaky grip as the teacher pauses, carefully adjusting my frozen posture as I try through both sweaty palms and stilted frustration and to begin.

In the years to come, I — like the half-million pupils each year that start with the Suzuki method — would grow into a small and adept violinist, a competitive student in a system that has churned out more accomplished players than perhaps any single method in history. Renowned musicians like Hilary Hahn, Rachel Barton, Jessica Guideri, Jennifer Koh, and David Perry each began with the program (“Among Pros, More Go Suzuki,” the New York Times suggested in 1982), and the method has grown to dominate the global conversation on musical pedagogy and youth education. Taking on students as young as three and four years old and squashing what once required years of study into a strict, incremental approach in ten books of sheet music, the Suzuki Method has largely subsumed all others as a sort of default method of violin instruction, one that now extends to numerous other instruments like viola, cello, piano, flute, organ, and even voice in renowned institutions across the world. Conferences like the Suzuki Association of the Americas meet annually with lectures and presentations and the system has its own strange and sprawling digital presence in forums and blogs, Facebook groups, Instagram tags, and YouTube channels, a surprising number of which are dedicated to video evidence of students completing the entire program by the age of six.

The method takes students through a ten sequential books, beginning with a few variations on “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” and following through famously complex works from Mozart, Bach, Corelli, and others. The pieces largely come from the sort of standard Baroque repertoire that would be taught formally throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, updated with a mix of children’s folk songs from Germany, France, and Hungary. Though completing the program doesn’t necessarily mean mastery, students who have the commitment to make it through the grueling 89 pieces (granted, some are movements in larger concertos and sonatas) tend to go on to play with high school orchestras, audition with conservatory programs, and make their way into the meticulous circuit of metropolitan symphonies in cities around the globe. Though most students either fall out before finishing or matriculate into public school programs rather than continue with the ear-oriented formalism, the full Suzuki program itself tends to take about ten or so years to complete, though this can vary widely under certain circumstances.

In the late 1940s, Dr. Shinichi Suzuki developed the method while working in his father’s violin factory in Nagoya, Japan. Despite being raised by violin makers, neither he nor any of his siblings ever had any aspirations to become musicians until one day in 1915, when a seventeen-year-old Shinchi allegedly heard a recording of Schubert’s Ave Maria. Inspired to devise his own self-education process, Shinichi spent the next few years listening to the recording over and over, slowly working out the mechanics of the song and instrument. Six years later, Shinichi moved to Berlin to study under the mentorship of German professor Karl Klingler, married German concert soprano Waltraud Prange, and returned to Japan to begin teaching his experimental ear-training technique to young students throughout the Tokyo area.

Much of the program’s proto-viral success lies in its track record for dazzling parents and educators alike with incredible outcomes from students of all ages. In 1936, Shinichi’s first student, the three-year-old Koji Toyoda, quickly delighted Tokyo newspapers after only four years of study, going on to win numerous awards in competitions, and eventually serving as concertmaster of the Berlin Radio-Philharmonic Orchestra. Others like Kenji Kobayashi would perform with world-renowned orchestras, earn coveted academic positions, and go on to start their own studios with the program, helping to expand the mentor’s message beyond the small island country of Japan to radically alter the course of music education globally. In 1958, students at Oberlin College would present a short film in which hundreds of Suzuki students performed Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins, inspiring academics like John D. Kendall to bring the method to the States himself, where over 350,000 children and adults alike still continue their education in the style to this day.

Through exposure to tonal exercises and early ear-training, the core of the program is built on the idea that nurture, not nature, has the most prominent impact on a child’s potential success in the arts. In his proleptic autobiography, Nurtured by Love, Shinichi notes that the “wrong education and upbringing produces ugly personalities, whereas a fine upbringing and good education will bring forth superior sense and feeling…all children adapt the vital forces of their organism to their respective environments.” Developed in Tokyo the 1930s, a time when music education was largely split between upper-class finishing schools and a handful of competitive conservatories largely confined to the West, Suzuki’s radical assertion that all could be musical — something that wouldn’t become fashionable in musicology circles until John Blacking’s How Musical is Man nearly three decades later — struck a chord with the global public, selling a methodic meritocracy where talent was built, not bred. Unlike most educational forms of the early-mid twentieth century that proposed the rigorous study of counterpoint, sight reading, and harmonic theory alongside performance, the Suzuki Method instead required all songs to be performed from memory, noting that, like language, children “add [each song] to their vocabulary or repertoire, gradually using it in new and more sophisticated ways.”

The parallels with language run deep. Music, like language, can be broken and into phoneme-like minutiae, taught as an accumulation of mechanical gestures, and applied to more and more complex pieces as a child’s talent grows. Elsewhere in Nurtured by Love, Suzuki writes of a certain biological aptitude that, like language, children have for musical instruction. Like Noam Chomsky’s famous assertion that a certain “Language Acquisition Device” allows children to grasp the complex constraints of even the most difficult languages in ways no longer accessible later in life, Suzuki finds that young students have a natural proficiency for aural acquisition, an assertion that later boarders on a sort of pseudo-scientific TED Talk bio-essentialism not limited to the musical parallels between certain Japanese nightingales and Osaka dialect. At one point, Suzuki invokes a certain 1941 lab test between Denver and Yale universities on children allegedly raised by wolves, who, after being socialized by the animals from birth, began to grasp objects with their mouths instead of hands, took water and food not limited to raw meats and vegetable “in a dog-like manner” and even had “head, breasts, and shoulders thick with hair.”

While so much of this pop psychology feels certainly dated in hindsight, the success of the program can’t be disputed. Freeing music pedagogy from the glut of developmental theory — which, beneath all else, showed even more impressive results with Suzuki — felt like an important victory for alternative education, and the number of independent teachers committed to the method would balloon into the tens of thousand throughout the 70s and 80s. Where most methods preached of righteous self-discipline, Suzuki’s focus on empathy and socialization through childhood development was one that made classical music — long out of fashion with North American students, especially in the late 90s when I began — approachable in a way that no other method would quite realize, at least not under the same constraints. Its encouragements of playful experimentation and agency gave the violin new life, so much so that the Times once, in reference Max Weber’s Rational and Sociological Foundations of Music, suggested it to soon displace the piano as the “consummation” of a new “bourgeois music culture,” a new, inexpensive default for youth musical education across the world.

The method isn’t without detractors; the program has long been the source of ire from competing methods, none as effective at ‘hacking’ the old institutional systems and streamlining youth education into the sort of blunt metrics and visible milestones that the American public education system loves, quite like Suzuki. Most recently, composer, author, and teacher Mark O’Connor turned heads when, in 2014, he boldly accused Shinichi of fictionalizing entire sections of his biography in promotion of the method. Where Nurtured by Love boasts of Suzuki’s achievements under the mentorship of German professor Karl Klingler, O’Connor revealed in a series of blog posts that Suzuki in fact had only auditioned to study under the professor, and was never accepted to study at the Berlin Hochshule where Klingler taught. O’Connor goes on to out Suzuki as never earning a PhD, never being endorsed by renowned cellist Pablo Casals, and never “mentored and watched after” by Albert Einstein, as are purported by his writing. Academics like John D. Kendall would go on to repeat these same inconsistencies, printed and reprinted by the press until firmly detached from realities, woven into a spotless narrative that bolstered both men’s reputations. “Of course Kendall had a huge stake in the potential Suzuki empire — he ran the SAA (Suzuki Association of the Americas) as its president for 30 years beginning in 1971,” O’Connor writes. “Was it all just about money, selling an exotic product from Japan to unsuspecting American violin kids?”

Counter-allegations, namely from the SAA themselves, would suggest that the stunt was done in promotion of the O’Connor Method, his own school with emphasis on the folk traditions of North America, but with a such staggering amount of archival research substantiating his findings, much of O’Connor’s outrage feels warranted. Whether or not a PhD is necessary to develop experiential education methods, much of Suzuki’s success in America was still bolstered by evidence of his institutional acceptance under a former Berlin Philharmonic concertmaster and without that, it’s both bizarre and, well, kind of impressive that the system ever got off the ground to begin with, almost purely on the electric success of the method’s world-of-mouth travel.

And so almost three years after this discovery, what, if anything, has changed? The Suzuki method is still overwhelmingly the dominant school across North America, and no other method has come to close delivering results with the same Earth-shattering impression glamor that the program once held, and perhaps never will. Even with a dubious background and an autobiographical manifesto bolstered by strange pseudoscience, what Suzuki brought to youth education has made the violin now more approachable than even the most seasoned competitors, allowing children, especially in low-income communities, to start on a path toward success in the arts. For all its faults, the fact that one particularly charismatic man from Japan — one who never attended college, barely studied at the professional level, and, especially in videos, seems barely able to perform some of the pieces himself — could radically alter the course of youth education feels like a wild and historically unprecedented development in a vastly conservative field of study. With his death in 1998, Shinichi Suzuki left a warm, humanistic impact on a procedural pursuit almost never associated with such, and even as his methods have been largely debunked as having more to do with rigorous practice than he’d ever admit publicly, the Suzuki legacy lives on in testament to his vision.