The Long, Twisted History Of Marvel Comics: A Talk With Sean Howe

The Long, Twisted History Of Marvel Comics: A Talk With Sean Howe

Marvel: The Untold Story is a meticulous reconstruction of the history of the other Marvel Universe. It’s the tale of the men and women who were creating all the characters and plotlines of the Marvel empire that currently dominates Hollywood. I’ve been as big a fan of the medium as anyone, for decades now, so I was glad for the opportunity to talk by phone to the author of this obsessive work, the very pleasant Sean Howe, who spent three years of his life writing this history. The book makes a great gift, as I hear Secret Santa season is upon us. And his Tumblr, it should be mentioned, is an invaluable companion to the book, with untold stories and the ultimate fates of some of the creators of the most popular characters of American culture.

Brent Cox: I never dreamt that anyone would get around to writing a book like this. So I have to ask: What were you thinking?

Sean Howe: I was waiting for someone to cover this story for a long time. I noted that every time that I was reading fanzine interviews with these comic book creators that they were telling this story that was a lot different than the official version.

What’s your own personal history with comic books?

I learned how to read from comic books when I was four. I was first sounding out words from comic books, and when I was eight was probably the first time that my dad brought me into a comic book store.

What store was it?

Dream Days, in Syracuse, New York. I’m 38; how old are you?

43. And same story with me, but my first store was Eide’s Comics, in Pittsburgh.

The thing is, this was before (as you well know) the Internet, and there was something about the comic book world, you felt like you were part of something bigger. I remember this feeling of, like, oh my God! I live in this small town and I’m isolated from so much, and I’m not into rock ‘n roll yet, and this is my first pop culture connection to the outside world.

In choosing to writing the book, you’re contemplating that more people than just comic book fans (like us) are going to read it. What do you think the appeal of the “inside baseball” story is?

I think that the story of Marvel Comics is a really clear way of telling the story of pop culture, and I think that the collisions between art and commerce are things that have application to pretty much any other creative industry. The thing about Marvel’s history that really highlights those battles and those contradictions, is that it’s this huge overarching narrative. If you think of the story of the Marvel Universe, the ur-story —

Yes, the continuity.

It’s almost like this giant river that’s rushing by and all these people throw their ideas into the river, and the river just keeps going without them. These creators for the most part have no financial ownership, and also no creative ownership. Eventually their creative contributions can be overruled as well. Television I guess is a little bit like this, but in television people are well paid.

Are people traditionally well paid in comic books? You do cite dollar amounts a couple times, but I imagine that you were trying to be circumspect.

There have been times where comic books paid well.

You mentioned writer Scott Lobdell making $85,000 a month?

Yes, in the late 90s, writing the X-Men titles. But the thing is, that’s not unusual for someone who would be a top TV writer. It’s only unusual in the world of comic books. And that was only at the height of comics’ success, on a title like X-Men.

One thing that really comes out in the book is how distribution is really the engine that drives the entire industry, from the late 30s when the entire thing was run by a handful of guys in midtown Manhattan who were basically magazine publishing companies fighting over newsstand rack space, and in more recent history, with comic book publishers winnowing the distribution market by acquiring distributors. Do you think that’s something specific to comic books?

I think that distribution is definitely a huge part of the story, and in fact I think that it’s probably the main explanation for why comic books are in the situation they’re in now. When the comic book specialty store market imploded, it’s not like comics still have that newsstand access.

You can’t still go to 7–11 and find them on the racks.

Exactly. And I don’t think that that fact is necessarily the fault of the comics industry. They were having trouble with newsstand sales in 1978. It’s just that they were able to put it off being a huge problem by finding the direct market. They never abandoned newsstands, rather, the newsstands abandoned them.

Another thing that struck me as I was reading is the ways in which the industry acted as a meat grinder. You don’t meet a lot of people that have been in it a long time that are happy. There’s an episode from the 70s with Stan Lee advising someone not to get into the business, and Frank Miller’s 1994 industry seminar keynote following Jack Kirby’s death is a real downer:

Marvel Comics is trying to sell you all on the notion that characters are the only important component of its comics. As if nobody had to create these characters, as if the audience is so brain-dead they can’t tell a good job from a bad one. You can almost forgive them this, since their characters aren’t leaving in droves like the talent is.

And yet it’s a field full of young hopefuls, eager to sign up. Why is that?

It’s their childhood dream and they’ve been pursuing it. I think that at this point, there’s a greater likelihood of people being happy. Not because the comic book industry is any kinder, but because people are going into it a little more clear-eyed than 30 years ago.

They’re forewarned.

Yeah. That’s one thing that’s been kind of amazing is to get a lot of feedback on this book, and there’s so many comic book readers that are just shocked by the facts that are in the book. They can’t believe that so many people were so screwed over and so many people were so unhappy at different times.

I had no idea that Jerry Siegel [the co-creator of the most iconic superhero ever ever, Superman] ended up working as a proof-reader at Marvel in the 60s.

That was a crazy moment. I had heard that, but then Chris Claremont was telling me that when he was like, 22, seeing this old guy, Jerry Siegel, and thinking to himself, “I’m never going to end up like that.” And now flash forward 40 years, and Chris Claremont is saying, “Now Marvel won’t let me write any comics. Characters that I created have their own books, and Marvel won’t hire me to do them.”

Ms. Marvel, which Chris Claremont described as Marvel’s attempt to “appeal to a female audience, trying to make her a hip, happening, 1970s woman striking out on her own.”

How many creators did you talk to?

Somewhere between 100 and 150.

And generally speaking, how many of them are happy?

Well, that’s hard to say. A lot of them are no longer in the industry.

By choice, or…

You know, they’ve retired or — it’s hard to generalize. Gerry Conway [co-creator of The Punisher] ended up being an executive producer of “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” so some people found some really nice outs. And then if they still are in the industry, very few people that are still in are going to tell me they are not happy.

Well, to think of these professionals as a group with a shared peculiar experience, like professional baseball players from the 60s, say, is there still a “joy of the game” in them?

Yeah. There is. There are instances where people pretty much have given up on thinking good thoughts about comics, but I think those are rare. The more common arc for these people is that they had some of the best times of their lives working on comics, whether they were in the office or they were a freelancer. And then something with the business turned, and as you know from the book, this happens cyclically, so it doesn’t even matter when they were working. Either they working in 1980 and something happened and everyone became unhappy, or it was 1996 and everyone got laid off. And then they go through a period of bitterness, and then they put it into perspective and they move on with their lives. Maybe they don’t work in the comics industry, maybe they work in advertising, or they have a start-up company, and they have still have their fond memories of the good days, and almost to the person have a great memory of when they met Stan Lee and he was super nice, and now they may or may not read comic books themselves, but they’re not completely at odds with the idea of Marvel Comics necessarily.

It’s one of the things I remember [Howard the Duck creator] Steve Gerber’s collaborator and one-time girlfriend Mary Skrenes was talking about how he never wanted to do anything more than write superheroes, and that became a big problem for him, just because all he wanted to do is to write these superheroes, and you only had Marvel Comics and DC Comics, and they weren’t treating him well, but he just didn’t know what to do with his life.

Steve Gerber in the 70s. Courtesy of Howe’s Tumblr.

Like he was someone that was born just to do that one thing.

Yeah.

Speaking of Claremont and Conway and Gerber, how many of your own personal heroes did you get to talk to for this thing?

Hm.

Let’s geek it out a little bit.

I don’t know that I — maybe it’s that I’ve been through the process, but I don’t remember being that star-struck. Certainly, the ten year old in me was excited to be talking to Frank Miller about Daredevil, and what was going on in his life when he was doing that, that was pretty thrilling. And talking to Stan Lee is like talking to an uncle you haven’t seen in 30 years, and there’s just something about the timbre of his voice that can send you back to childhood.

He’s been living the gimmick for more than 50 years.

Right. You’ve heard his voice in the Saturday morning cartoons since you were a little kid. It’s a very comfortable voice. And just that alone is kind of a thrill.

Did you get a lot of resistance from people when you were trying to research this?

No, not really. I mean, people were sometimes were tight-lipped. I would say that the biggest obstacle would simply be that people who work in the comics industry are afraid of burning bridges, professionally. Not in the sense of talking behind anyone’s back, or anything like that, but people are afraid that if they say something critical, it’ll be bad for their career prospects.

Another thing you covered well was the legal issues that run through the industry, the IP and the struggle between Marvel and the creators.

They’ve always had lawyers, but I think Marvel really started nailing down the rights in the mid- to late-60s. You know in the upper-left hand corners of the books from the 70s and the 80s, with the heads of the characters of the book?

Yes.

That’s not to help the reader identify the books. Those were put there for trademark purposes.

I did now know that’s why those were there! So they would trademark the little floating heads?

Yeah. Actually, let me look. Yeah, there’s a little trademark symbol next to them.

Actually, that’s something I’ve been wondering reading the books, and actually for years. I have experience in entertainment law. How do you copyright a character? Because you can’t, in my understanding, as copyright protects only the fixed expression of an idea. So you can trademark a character’s name, but…

They copyright the actual printed issues.

Oh, okay. But you hear creators talk, about how they want the copyright in the character they created…

If you look at the actual filings, there won’t be a lawsuit over the character of Captain America, but what they actually cite is “Captain America Comics” issue number one, and that’s the copyright that they’re going after.

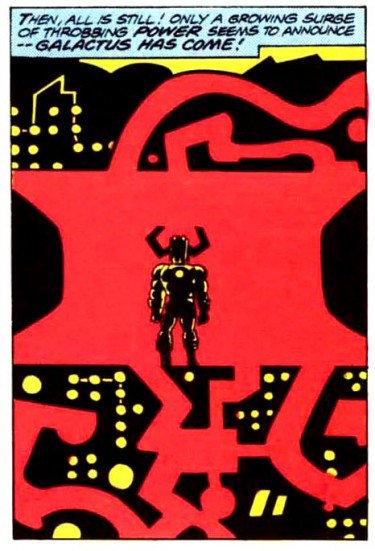

Galactus art by Jack Kirby. More here.

You do a very good job of constructing a straight-forward narrative. How do you stick to this narrative and not superimpose your opinions on some of the controversies that pop up?

Obviously, I have my opinions and my biases, and those are going to come through, whether explicitly or not. I felt like, especially within the world of people that write about comic books, there’s no shortage of polemics. There’s a lot of really strong opinions and a lot of rhetoric, and I thought it was really important to just lay out the facts of what happened, and to present, for example, this is what Jack Kirby said happened, and this is what Stan Lee said happened, and not try to contaminate those facts with arguments. I think that I’ve done it in such a way that people can draw pretty informed conclusions about the way things happened. But I don’t know who, Jack or Stan, did more in creating the idea of the Fantastic Four, say.

And nobody ever will.

And probably no one ever will. Who knows if there will be unearthed documents at some point? But it’s probably not going to be an eleventh-hour Stan Lee revelation.

There’s not going to be a security camera that recorded that.

Right. But what I did find was things like Stan Lee talking to someone in 1969 about how he was somewhat disillusioned with Marvel Comics and he wanted to bring Jack Kirby to Hollywood with him. And I’ve read before Stan saying that that’s what he wanted back then, but you never really know, when it’s 30 years ago, how true that was, or what the spin was, but when you hear a recording of someone talking about their current feelings, that’s really valuable.

This also comes up a lot in the book, professionals worrying at various points in history that the industry is not going to be there in five years. Do you think the industry is going to be here in five years?

Yeah, I think so. I think it may very well go through some really tumultuous times. For one thing, it’s Time Warner and Disney who control the biggest comic book companies. Maybe it’ll be that they just start putting out graphic novels on an irregular basis, but it’s not like they’re just going to walk away from money. I know that Marvel is profitable. I’m pretty sure that DC is profitable on the publishing end. I mean, on one hand, it’s kind of annoying that Marvel’s bottom line, the way that they’re set up, they insist that the publishing be self-sufficient, which means that they won’t use their movie money to subsidize experimental, loss-leading creative ideas in the comic book world.

I was looking at some current sales numbers this morning, and I was shocked. They’re low. You know, some titles are selling only 6,000 copies a month. It seems that the economics of it are confusing. But I guess if you have some books that are selling 175,000 copies…

And you’re charging three or four dollars, and, you know, they’re not paying anyone $85,000 a month anymore. Plus you’ve got a pretty lean staff of editors as well. There’s not a huge amount of overhead.

So are you going to write a book about DC now?

[Laughs.] I don’t have any plans to write a book about DC, but the news of [influential, long-time editor of DC’s Vertigo line] Karen Berger departing did get me thinking. I’m really interested in the story of DC in the 1980s especially, but I spent a lot of my life thinking about Marvel Comics in particular.

Related: Adjusted For Inflation: How Much More Do Comic Books Cost Today? and Batman-ish: What Comic Book Movies Are Missing