Is San Francisco The Brooklyn To Silicon Valley's Unbuilt Manhattan?

Like many people who moved to San Francisco in the early 1990s, I did it because San Francisco was cheap. It didn’t have the lowest rents — in the California of three recessions ago, a Silver Lake bungalow or blocks-from-the-beach Santa Monica apartment were even more affordable than the chilly city by the bay — but it was the only West Coast town you could survive in without a car. With a $35 Fast Pass, all the smelly buses and dinky Muni trains and even the cable cars were there for the riding to and from work, whether you were a bartender or a waiter or (like me) a very fast typist irregularly employed by temp agencies. It was fun, mostly, but it also felt like a town imprisoned by a past of already crumbling 70s architecture alongside the beloved Victorians, weary from 60s hippies and 80s punks, AIDS and fern bars. (Did you know that the fern bar was created in San Francisco back in 1970?) When I worked in the Financial District across from the Transamerica Pyramid, I would put on my trenchcoat and leave my Sam Spade flat at Bush and Leavenworth and walk up the hill through the fog and drizzle to hop the California Street car headed downtown, where the ruins of the Embarcadero Freeway were still being hauled away. It was the prettiest town around, and it was a bargain.

The first text-and-images Web browser, Mosaic, was released at this very moment in time, the spring of 1993. A year later, Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark launched Netscape Communications with Silicon Valley money. They based the new company in Mountain View, alongside the tech companies that spread over the Santa Clara Valley in the decades after Hewlett-Packard launched from a Palo Alto garage back in 1939. Wired, the magazine that would define the first decade of the Internet Era, didn’t launch in Silicon Valley. It set up shop in San Francisco.

In 2013, the bigger tech companies are still in Silicon Valley, but the people working there — from Mark Zuckerberg to the newest $100K hires straight out of college — want to be in San Francisco. Zuckerberg is a part-timer, with a fancy apartment in the Mission. The rest are part-timers in Silicon Valley, commuting to and from work on immense luxury buses run by Google, Apple, EA, Yahoo and the rest. This has caused problems, notably for San Francisco residents unlucky enough to survive on less than a hundred-grand starting salary. Talk of raising the city’s skyline is met with anger. People argue endlessly over the appropriate comparisons to New York. Is Oakland the Brooklyn to SF? What about Berkeley, or Marin, or the Outer Sunset? And what does that make Bayview or Burlingame?

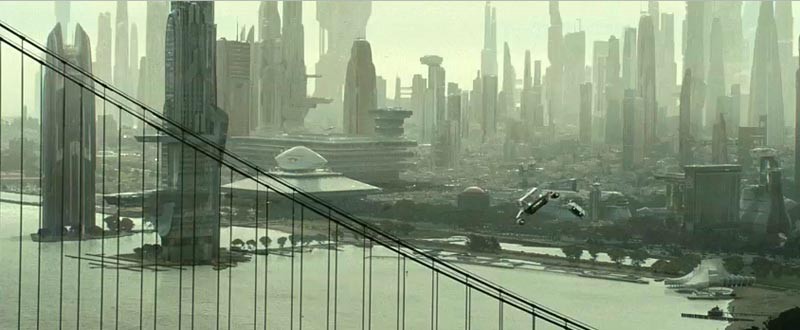

All of this assumes that urban San Francisco equals Manhattan. It does not. San Francisco, with its leafy parks and charming row houses and distinct villages and locavore restaurants and commuters fleeing every morning to work, is the Brooklyn to an as-yet-unbuilt Manhattan.

There are tech companies in San Francisco, with Twitter’s takeover of an unloved chunk of Market Street at the foot of Polk Gulch the most conspicuous new example. But there’s no room in the city for anything like Apple’s 176-acre spaceship headquarters being built in Cupertino, and there’s no reason for the whole of Silicon Valley to gaze up at the peninsula, and the whole problem in San Francisco today is there’s not enough housing for humans when they’re not at work.

As disappointed visitors and new employees discover, Silicon Valley is a dull and ugly landscape of low-rise stucco office parks and immense traffic-clogged boulevards. The fancy restaurants are in strip malls, like you’d find in Arizona or something. There is nothing to do, nowhere to go. Massive arcologies like the new Apple campus are where the tech giants are headed, but until there are living urban neighborhoods connecting these monstrosities, anyone with hopes for a life outside of work will pay a ridiculous premium to live in San Francisco and spend two hours of every day sitting on a bus.

Meanwhile, the areas around and in between the tech giants of Silicon Valley are mostly ready to be razed and rebuilt. There are miles and miles of half-empty retail space, hideous 1970s’ two-story apartment complexes, most of it lacking the basic human infrastructure of public transportation, playgrounds, bicycle and running and walking paths, outdoor cafes and blocks loaded with bars and late-night restaurants. This is where the new metropolis must be built, in this unloved but sunny valley.

And then the new supercity gets linked to San Francisco by an existing boulevard of run-down old malls and decrepit car lots that pours right into the Mission District and downtown SF, 40 miles north. The boulevard is El Camino Real, or California Route 82, the one-time king’s highway that could be a new corridor of high-rise apartments and HQs and restaurants and museums filling in the long gaps between downtown San Jose and Apple/Google/HP/Yahoo/Intel and Stanford University and San Francisco. With local light rail at street level and express trains overhead or underground, the whole route could be lined with native-landscaped sidewalks dotted with pocket parks and filled on both sides with ground-floor retail, farmers markets and nightlife districts around every station. Caltrain already runs just east of Route 82, and BART already reaches south to Millbrae now.

Open space is weirdly abundant and well protected here, with a 25-mile length of redwoods and hills including the state fish and game refuge, several state and local parks, and various preserves stretching down to Pescadero and all the way north to Pacifica.

El Camino Real is already the focus of various plans to connect Silicon Valley and San Francisco, from Caltrain’s own future scenarios to the Grand Boulevard Initiative, the dozens of cities and towns and jurisdictions on the peninsula are beginning to figure out the old way of just building cheaper crappy suburbs all the way to the Central Valley is not going to work any longer. Nobody wants to move to the Bay Area for work and then discover they actually have to live in a completely different climate an hour’s drive (without traffic) from the actual bay. The magical part of the Bay Area is really confined to the Bay Area, with its relatively green hills and foggy mornings and cool ocean air. And in the post-automobile era, where else would you look to expand your metropolitan area other than the underused sections in the middle of your metropolitan area?

Building costs money, but the whole planet’s technology business is centered in Santa Clara County, down the road from that other Gold Rush town, San Francisco. Just because Silicon Valley boomed during the ugliest age of mainstream American architecture doesn’t mean Silicon Valley has to keep all those horrible beige buildings on their seas of asphalt parking lots.

Or maybe it’s too late already. Last year, San Francisco had a 10% jump in tech employment. Silicon Valley had only a 3% increase in technology jobs. Twitter, Yelp, Quantcast and Pinterest are some of the bigger names that have made long-term bets on San Francisco as a Tech HQ town. There are tax breaks and incentives, but the main reason is because the people who run these companies would rather live in a beautiful urban center than some worn-out 1970s sprawl.

Ken Layne is about to move to San Francisco again, for the third time in as many decades.