Earth Is Just One Really Big Google Map

In my other life, I know where I’m going.

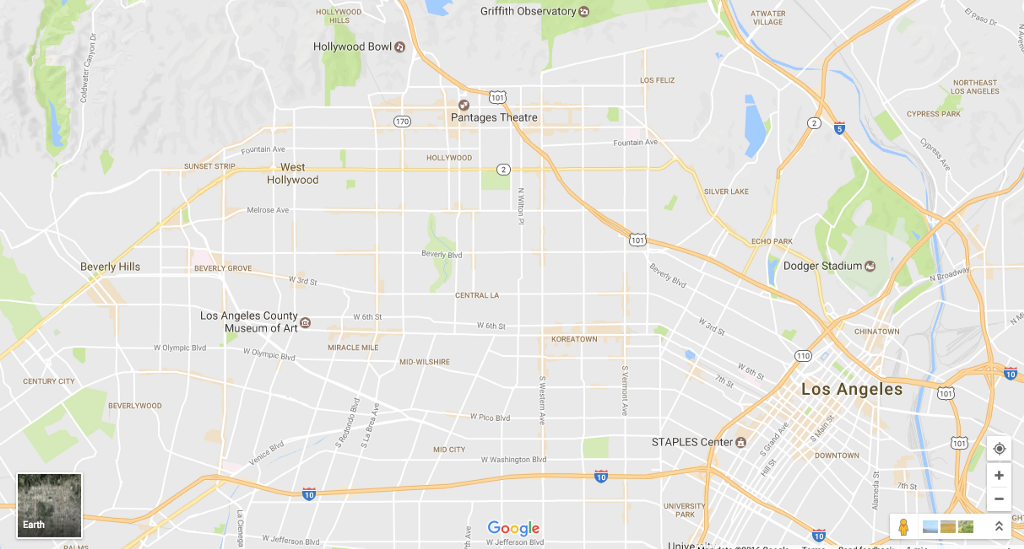

The traffic is so bad in Los Angeles that Google Maps tells us to stay off the highway. I guess this is obvious to anyone who lives there, but I don’t. On my way toward Culver City from Los Feliz — two neighborhoods I wouldn’t be able to locate without Google Maps — I follow the gentle voice of a GPS as she guides me through a zigzag of backstreets, due southwest. It isn’t a bad way to see a city I’m not familiar with. I pass the shops of Koreatown, the Victorian mansions of West Adams. Because LA is a grid, its scenic route is a series of alternating left and right turns.

Every trip I take — for business or leisure — is contextualized by Google Maps. But relying on the GPS means never really getting situated. Even after I leave a new city, I feel that my spatial awareness of it is about as good as it was when I arrived. Google Maps means I’m never lost, but I never really know where I am either.

I worked full-time at Google for six months as an editor. Google makes the majority of its revenue from advertising, yet employees were reluctant to ever refer to it as an advertising company. I was told repeatedly that it was a technology company, a hub of innovation. Most of people drank the Kool Aid, except it wasn’t Kool Aid so much as lightly flavored water available in bountiful refrigerators around the office.

One day, I received a meeting invite titled “Algorithmically Generated Content.” A stranger at the company was very excited to talk to me about using computers to write content rather than relying on human beings. Like a lot of the meeting invites I received from strangers, little context was given. It was an alarming email to receive as someone who writes and edits for a living. I’d like to think that my skills can’t be replicated by a computer. But then I think about just how many computers Google has.

I later heard that the content that was being generated was for Maps. Google had acquired Zagat in 2011 to integrate the restaurant guide with the company’s location data. Apparently the integration had not gone well. Most location and restaurant descriptions were sentence fragments, written by a small team of freelancers. That was decidedly “unscalable,” and now, Google was trying to phase out Zagat descriptions and replace them with computer-generated ones. I have no idea if the computer-generated location descriptions were ever implemented. The beautiful thing about meeting invites is that they only take a single click to decline.

An incredibly popular smartphone game was released over the summer — an augmented reality game that uses real-life maps and locations dressed with an added fictional layer. As you walk around, the phone buzzes to let you know there is a cute monster you can catch. The collectible creatures can be found by roaming your local environment, which often involves bumping into other players doing the same thing. The game was built on Google Maps by a mobile gaming company called Niantic, formerly owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet. It is, essentially, a game made by ex-Google leadership on top of a Google platform, masqueraded by the license of a very popular videogame franchise.

Like most mobile games, this one is free; it makes money from its own currency. Players can use real money to buy fictional money, which can be exchanged for items in the game. Niantic has confirmed it will begin selling sponsored locations to brands as another means of revenue. The idea is that businesses can lure players to their stores and restaurants by increasing the number of collectible creatures available in the surrounding area. Niantic created the fiction that lives on top of Google Maps; they can add whatever they want to it. Soon, advertisers will be able to use real money to buy preferred placement on a fictional map that will lure players to real locations. It’s not terribly different from the way advertising works on Google Maps now. As with Google search results, sponsored slots can be bought. Through the Google worldview, all real estate is for sale.

On our last night in LA, my girlfriend and I tell friends to meet us at a bar called 4100 Bar in Silver Lake. Google Maps describes the bar as a “dimly lit intimate lounge.” I would describe it as “too crowded, too dark, and too loud.” Friends show up anyway, even though everyone seemed to know already that it was an awful bar. The next morning, I punch our destination into Google Maps. The software doesn’t recognize that the entirety of Vermont Avenue had been closed to be repaved. But no matter. We drive around a corner and the GPS voice politely explains that she was recalculating our route. Again we are instructed to avoid the highways.

I think about the trust I’ve put in Google Maps. It’s earned it, I suppose, given how much I’ve depended on it in the past decade. Four years ago, when Apple replaced its default Maps app — one that relied on Google’s mapping data — with a version backed by Apple’s own. It was a move for one tech giant to pull its reliance on a competitor. But people were outraged. I was outraged. On countless occasions, Google Maps has gotten me to where I needed to go. It has also turned me into the kind of person who gets mad about an app.

As we navigate that back roads of LA, I think about how we’re “making good time.” When I’m driving, I am always overly concerned about making good time, even though I’m not sure why. I assume Google Maps is getting us to where we need to be as quickly as possible. But do I really know that it has my best interests in mind?

One company controls the way we see the world and directs how we move through it. You have to trust that the world it presents doesn’t have other incentives or motives. But of course it does, because the reality is that Google Maps is an elaborate work of fiction — a giant framework of coded human will forced over data, some of it wrong and some of it distorted — and yet we trust it to tell us our place in the world.

Kevin Nguyen is the digital deputy editor of GQ.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.