Subject Test

In my other life, I brought the right pencil.

To apply for a doctoral program in the United States, a person takes certain examinations. The big one is the GRE, which stands for Graduate Record Examination. It’s a standardized outfit that tests “verbal reasoning, quantitative reasoning, analytical writing, and critical thinking skills that have been acquired over a long period of learning and that are not entirely based on any specific field of study outside of the GRE itself.” I took it in London, sitting in front of a computer, like when you take the theory part of the driving test.

Beyond that, certain fields and certain schools require more testing. Law has its own kind of test, as does med school. Only one university that I applied to required the GRE Literature in English Subject Test, but I took it anyway. The Subject Test is not administered via a computer, like the main GRE. It is a multiple-choice test done on paper under the gaze of an invigilator. The candidate brings her own pencil.

By the time I booked my Subject Test, there was no space to take the test in the city I lived in. But there were a few spots left at an 8 a.m. test in Leeds. Situated somewhere between the shoulders of England, Leeds was a hundred and seventy-five miles from my home. So, there was no way to take the train on the same day of the test. It would have meant getting on the train in the middle of the night. I booked a room in an ibis hotel, and planned to travel up the night before the test. The corporate style is to write “ibis” in lowercase.

I got to the ibis from the train station at maybe 7 p.m. At the time, I was working on an essay about Beowulf, sinking deep into its gloomy and beautiful world. The essay was about the way time works in the poem, its sense of history. Here’s a footnote from my Beowulf paper, justifying a reading that Hrothgar reads runes carved into this one swordhilt supposedly manufactured by giants in the poem:

[1] ‘runstafas’ would seem to suggest a written inscription, and it is obviously logically anachronistic to suggest that a common language or script would be shared by the ‘enta’ and Hrothgar, but this does not preclude the poetic suggestion that he can. At any rate, ‘sceawode’ is ambiguous.

It’s a great moment in the poem. So, I sat and read Mircea Eliade’s Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism while eating a sandwich and drinking a beer in the ibis dining room, which was really more of a bar area, panelled in pale wood. Once I was done eating, I drank another beer and read a different book, about dragons. Where they came from, what they meant, and so on.

The next morning I woke a little before six to walk over to the exam. Years later my colleagues and I would return to that old stone building for conferences. Other test-takers crowded outside the building’s heavy wooden door. The sun was hardly up. Its light was weak and the cold old stone seemed to drink it up.

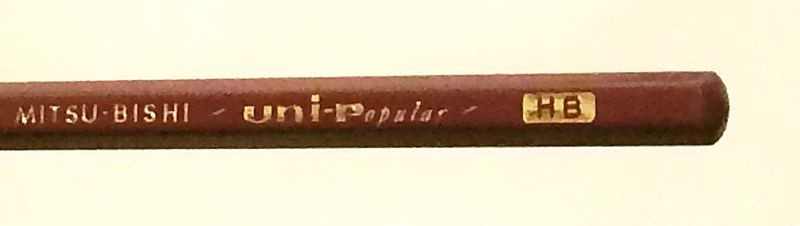

A candidate for the Subject Test must bring her own pencil, the rules dictate. That pencil must be a #2 pencil. However, in the U.K. we do not use this system of pencil classification. So, the crowd outside the test location was abuzz with discussion. Is an H.B. pencil the same as a #2 pencil? It must be, we reasoned, since that’s the ordinary type of pencil. But why would they specify the type of pencil unless the pencil was somehow unusual, not obvious? One girl had flown from Ireland to take this test. I hadn’t brought a pencil at all, having not read the instructions. I crossed the street to a nearby newsagent and bought a pencil without even thinking to ask what sort it was.

An online article tells me now that “The American #2 pencil usually lines up with the European HB grade,” although “there is no industry standard for the hardness of a lead grade and results vary from brand to brand. Japanese leads tend to be darker than their European equivalents, though they use the same system.”

The pencil conundrum didn’t matter in the end: the invigilator had spares. We filed in to sit at assigned desks. The test began. It was made of questions like this:

8. In lines 7–8, “to stand in thine own conceit” most nearly means

(A) to give yourself over to dissipations

(B) to keep yourself aloof from others

(C) to consider yourself superior to others

(D) to hold inflexibly to your own viewpoint

(E) to be duped by those who would prey upon your vanity

Each list of multiple-choice options was a glorious poem of nonsense. Every question was an anachronistic jumble, a large proportion of which was about American writers none of us had ever heard of. People in the room giggled. The testing room had a large window, paned in many rectangular pieces of glass. A leafless tree waved outside, tapping the glass occasionally like in Wuthering Heights as if to say that it saw how funny all of this was, how amusing that there is no international standard for grading how hard or soft a pencil is but that there is an alphabetized list of ways to define what John Lyly meant in the sixteenth century by “conceit.”

8 a.m. on a cold morning in 2009 feels like a long time ago, but it isn’t really. It would be interesting to calculate what fraction of the time since Beowulf’s composition has elapsed since then. Unfortunately, we don’t know when Beowulf was written, so we can’t. The time we test-takers spent laughing gently over the GRE Subject Test early on a cold northern morning seems now to have been carved out of time, pried out of history to show how there is no true scale for these things. (Like the dinner party in Tender Is The Night).

There can be no classification for meaning or pencils or the time between minds who have cared about poems. There is no real system behind the classification that turns you from a person into a doctor of philosophy or master of jurisprudence or a person who was rejected from grad school. These things are as arbitrary as the lowercase “I” in ibis. But how wonderful it is, sometimes, to stand in one’s own conceit.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic in New York.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.