Yakkin' About Tinfoil

In my other life, I’m a weird historian.

Before I ever learned history, I learned that there were histories that were rumored to exist behind them.

I grew up during the Reagan Administration, and that was a very special time for not ever being trustful of what was actually going on. This was true even without searching out the zines and pamphlets and tiny press publications, as I did later in life. When Ronald Reagan ran for president against Jimmy Carter, at issue was the Iran hostage crisis, in which the Shah of Iran was overthrown and the overthrowers seized the American Embassy in Tehran and held Americans hostage. The lack of resolution of this crisis (and failed rescue mission) was held to the account of the then-president, Mr. Carter, who lost. On Inauguration Day, when Mr. Reagan was sworn in, the hostages were released. I was a child, and that timing seemed seriously messed up to me, like Iran had picked a side in the election and was helping.

This later morphed into the Iran-Contra Scandal — a demotion from crisis, apparently — which provided the rest of the decade with a quiet backdrop of hearings and non-denial denials and eventual pardons. Coupled with the faith in institutions that we were schooled in was the sense that the institutions were deeper under the water line than they appeared, and that the mechanisms by which they operated were immoral if not unknowable, and for our own good, for better or for worse. I suppose it was a comfort to some, but to me it was, again, seriously messed up.

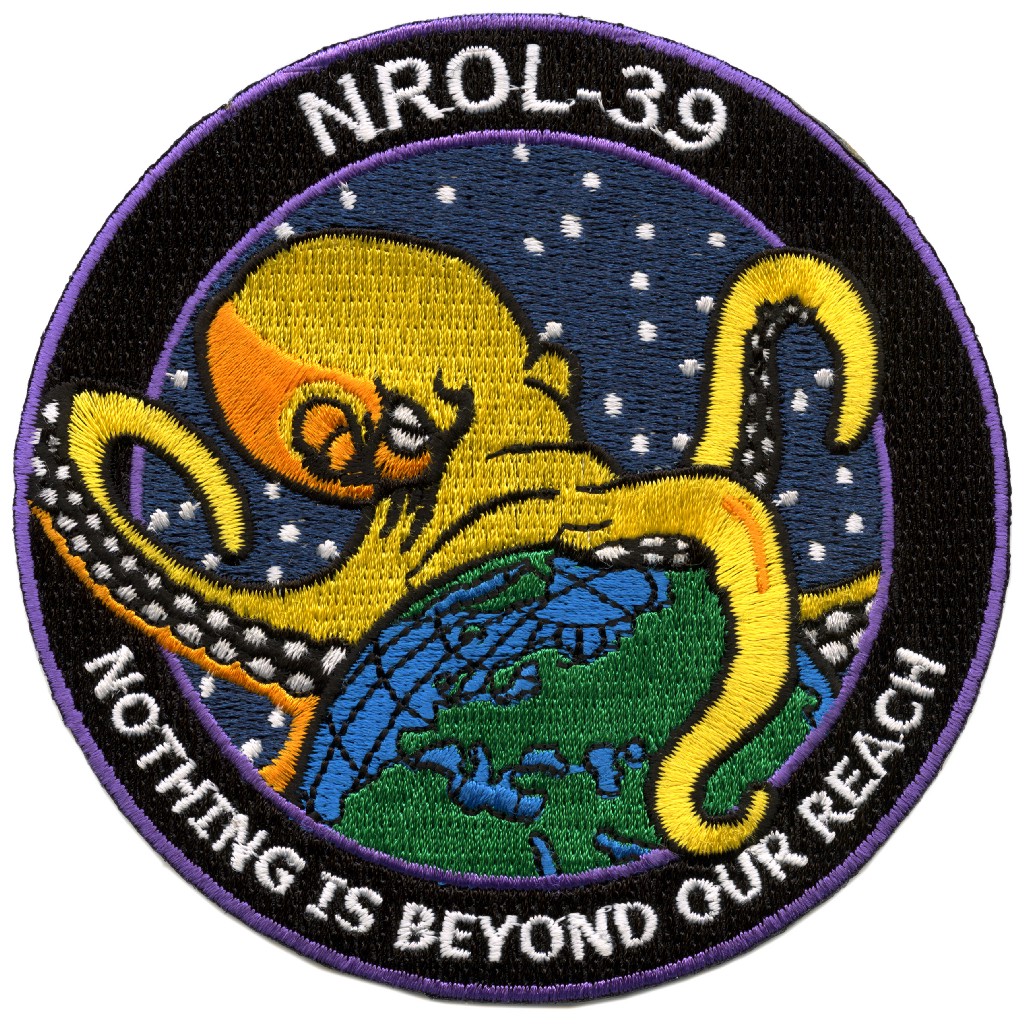

Then came The Octopus. It’s a bit fuzzy where I first read of it — I think the Village Voice? — but the nut of it is that a sometime-journalist named Danny Casolaro was found dead in a hotel room in Martinsburg, West Virginia in August of 1991. His body was found on top of a razor blade in a tub, and his wrists were cut. He was on assignment, he told his confederates, working a story in which he’d uncovered and exposed a group of intelligence officers — active and retired, domestic and foreign — who were attempting to exert hidden influence on the events of the world. He dubbed this “The Octopus,” and warned friends and family that The Octopus was onto him; if anything happened to him, it would not be an accident. After which something promptly happened to him that looked like an accident.

The details of The Octopus canon were terribly complex but for once set out in plain text and not hinted at, stretching back to the J.F.K. assassination and skidding through Watergate and the Iran-Contra Affair, a cast of characters that matched up well with conspiracy theories that preceded it. What set it apart is that it purported to be the Unified Field Theory of how the government actually worked, a glimpse at a precursor to what now is respectfully called the Deep State. (If you’re interested, and of course you are, wade into this.)

Around the same time the Gulf War is shockin’ and awein’, so no reason that Casolaro’s mysterious demise should be remembered as anything as fodder for a basic cable anthology show. But it was covered at the time, not only in the Village Voice, but also in Vanity Fair and Spy (and the NYT). The MacGuffin for the coverage at the time was a piece of software called PROMIS, intended to be used as a catchall surveillance tool crawling all the US law enforcement databases, which was developed and then (allegedly!) stolen and then (allegedly!) sold, etc. It was very cinematic, and it had the ring of enough truth to drive home the concept that the events of history —as read in a book or in the newspaper — are quite possibly incomplete events, and maybe history is weirder than it’s comfortable to admit.

And what’s the point of having all this weird history if we’re just going to forget it? This is why in my other life I am a Weird Historian.

Conspiracy was an enormously dumb catch-all phrase long before Alex Jones spittled it into oblivion. To speak of the unknowables of the world as conspiracy reveals a naïve certainty that not only everything happens for a reason, but also that the reason is that people chose to make it so. This is fine when talking about who shot J.F.K., as it is hard to make the argument that no one shot J.F.K. Even bona fide conspiracy theorists (i.e., people whose interests prevent them from being a polite dinner party guest) avoid the label at all costs. Conspiracy theorists sometimes mistake the trees in the forest as fingerprints, and conspiracy theorists need a good, dimly-lit secret hideout in which to really uncover the hidden truths. Conspiracy theorists are still working on a more respectable word that is as succinct and meaningful as sheeple, but will keep using sheeple in the meantime.

A Weird Historian, in comparison, is not solely a conspiracy enthusiast, but a buff of the stories that didn’t make it into the books. Earlier this month, the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor living in infamy was observed. But it was also, as dubbed by Alexander Cockburn, a day of “one of the great unsayables of 20th-Century American history,” as there are indications that the F.D.R. Administration had foreknowledge of the attack, allowing it to happen to sway isolationist sentiment in the U.S. to support declarations of war. This is hotly contested, of course, as it implies that 2,400 servicemen and -women were sacrificed for the sake of strategy.

Those who would convince you of the merit of the claims would show you testimony and interviews detailing how U.S. cryptoanalysists and Bletchley Park in England had cracked Japan’s cipher used to communicate with its diplomats, and how U.S Naval intelligence was monitoring the Japanese fleet in the South Pacific as it zeroed in on Hawaii. Arguing whether this did or did not happen has traditionally been aimed at tarnishing or protecting the reputation of F.D.R., but in my own personal work it’s just another bright shiny thing that I have polished and stashed away; another reminder that causation is impossibly complex and that the truth exists as a prize to be won.

And remember the Bonus Army? When F.D.R. was inaugurated for the first time, a fascist military coup was plotted and prevented, when the spiritual leader of the Bonus Army, Gen. (Ret.) Smedley Butler, then the most decorated Marine ever, tapped by the cabal of conservative businessmen to be the figurehead and rouse the troops, blew the whistle. Reaction at the time was dismissive, and the (first!) House Committee on Un-American Activities took testimony of Butler and one principal but pressed no charges. Is that not a bit of pertinent and interesting historical information? Newt Gingrich, a prominent advisor to the incoming presidential administration has admitted to a goal of rolling back F.D.R.’s New Deal — is it not relevant that at the time of the inception of the New Deal disgruntled financiers tried to deprive F.D.R. of office before he got the chance?

This bit of historical ephemera is by no means secret. But this is to me so much more interesting than the maybe-alien craft that crashed in Roswell, NM, and even more interesting than the giant U.F.O. that was photographed and fired upon over Los Angeles during World War II, which is very interesting in the sense that barely anyone remembers it. It was in January of 1942, the West Coast was on blackout (i.e., no exterior lights after dark that would serve as targets for enemy bombing runs) as we were at war with Japan, and an enormous craft floated over Santa Monica, and took two thousand rounds of anti-aircraft shells. (Here’s a page with repros of the reporting at the time.) Maybe that thing was an alien craft or an interdimensional blimp or a floating space elephant. We don’t know. But it didn’t start a war and it didn’t nearly overthrow the president of the United States. Weird.

This is not to say that weird history does not involve groups of people authoring events in a secretive fashion — more specifically, weird history is not contingent on groups of people authoring events in a secretive fashion. See, for example, The Octopus, though my personal Weird Historian opinion is to treat The Octopus how a Unitarian treats the Bible and not how a Southern Baptist does. If to a hammer everything looks like a nail, then in weird history every nail does not look like the Illuminati or the Trilateral Commission. Every nail looks like it leads to a whole lot of more interesting nails. Take, say, 9/11. Some think that actors other than Al Qaida were responsible for 9/11, to the extent that jet fuel melting steel is now a dad joke. Weird history would stipulate that 9/11 is a very interesting prism through which to view the events of the day.

History is repeated first as farce and then as tragedy. Weird history is farce and tragedy in the first place.

Something uncomfortable about this other life is when I run into anyone from outside the U.S. and Western Europe who shares these interests, they tend to laugh and laugh at me. Apparently, in the context of the rest of the planet, I am on the naïve end of the spectrum of foolishness, whispering about things that everyone else already knows. Why, my own very country, they remind me, was the single greatest secret author of events in the past two hundred years — a very impressive resume, including Iran in 1953 and pretty much the entirety of the Caribbean, Eastern Europe and Latin America. Hell, even Gen. Butler came to wide renown post-retirement by claiming he had been a Gangster For Capitalism, commanding forces that made non-U.S. parts of the world safe for U.S. companies. What am I, my foreign friends ask, some kind of asshole?

I see their point.

I foolishly presumed all citizens of every nation were taught that they are inviolable, that they are imbued with talent and grace exceeding that of citizens of all other countries and precincts, and that when the grace of God flows, it flows through the instruments of their nations only. Though when I think of it, was it implicit that the exceptionalism was supposed to be construed with a wink? You’re unique and special, just like everyone else? Or is that a conclusion I swiped from someone on Twitter citing Howard Zimmerman?

This other life — the one that I’ve decided I’ve been living for so very long — is very timely, what with the recent turn of events. Another life working for a think tank with the word PROSPERITY or GROWTH on the letterhead might have been more beneficial, but I don’t think they let you pick that particular other life so capriciously. As long as history keeps being weird, I’m not going to run out of things to do.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.