That Face! The Uncanny Art Of Studio Photography's Heyday

That Face! The Uncanny Art Of Studio Photography’s Heyday

by Jacob Mikanowski

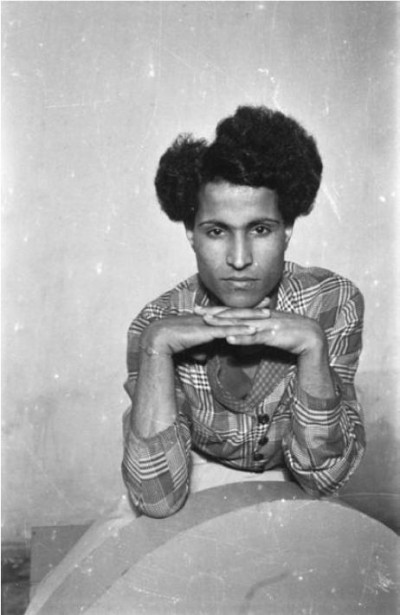

Ahmad el Abed, a tailor. Saida, Lebanon, 1948–53. by Hashem el Madani.

Collection: AIF/ Hashem el Madani. Copyright © Arab Image Foundation.

No product of human industry is infinite, but photography comes close. In 1976, John Szarkowski, the longtime curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, announced, somewhat gnomically, that “the world now contains more photographs than bricks.” As a metaphor of plenitude, Szarkowski’s phrase is wonderfully material, suggesting that photographs are just another object in the world, at once essential and interchangeable. As an estimate of quantity though, it now seems impossibly low. If digital photographs count (as by now they must), then the real figure must be several orders of magnitude larger, closer to the number of stars in the galaxy or neurons in the brain. And if I had to guess, I would expect that the majority of these photographs are of faces.

For a long time, photo portraits were restricted to a few places: in wallets, on ID cards and passports, in police files and high school yearbooks, on walls and desktops, on tombstones and wanted posters. Now they’re everywhere: on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr dashboards, they follow us around in a constantly updating cloud. Photography has become a means of autobiography and a broadcast art. It’s a way of keeping track what we wore last year and telling the world what we did last night. But as portraiture has become ubiquitous, it hasn’t gained in power. The ability to pierce or possess the viewer is still given to only a few images out of the billions.

Before Facebook, there was the photo studio: a room, a camera, and a photographer. Once upon a time, studio portraiture was an essential part of the visual vernacular. Like most vernaculars, studio photography was at once ubiquitous and invisible. Along with mug shots, crime scene photographs, aerial surveys and family snapshots, it belonged to the teeming undergrowth of photography, the network of practices and forms that sometimes predate and often anticipate its emergence as a recognized art form. In the hands of its greatest practitioners, it’s without question an art in its own right. But great portraits can also be the result of bureaucratic procedure, automatic gesture, or blind luck.

Studio photography is always at risk of seeming banal, and indeed, most of the photographs produced in portraiture’s heyday seem today either rote or bland. But a few of these photographers made work that remains indelible, and one of these was Hashem El Madani. For fifty years, beginning in 1949, Madani worked as a photographer in Sidon, a city in southern Lebanon. He began as an apprentice for a Jewish photographer in Haifa. After the events of 1948, he moved to Lebanon. At first he took pictures of his friends and family members. A few years later, he opened his own studio, called the Studio Scheherazade, above a cinema of the same name. With time, he became Sidon’s leading photographer. By his own estimate he photographed ninety percent of the people in town, amassing an archive of some five hundred thousand images.

Madani was a craftsman, providing a vital service for the people of his adopted city, taking photographs for ID cards, passports, weddings and christenings. But he was also an artist of rare power. His portraits preserve their subjects’ individuality. Unlike the work of artists like Richard Avedon or Diane Arbus, these photos don’t attempt to unmask or expose their subjects. Madani’s work is intimate without being intrusive. His photographs are often masterful, but they can also be rote or workmanlike, and their full impact only becomes clear when they are viewed in aggregate.

What Madani’s archive amounts to is an entire city, in faces. History moves through these photographs like a breeze through an open window. Fashions slowly change. The Ba’ath Party sets up shop on the floor above, and politicians come in for their campaign portraits. Palestinian militants stop by. Some look like soldiers, and others look like anxious kids. American oil executives come nodding in for a brief appearance, before ducking back out. When the civil war starts, two agents from Syrian Intelligence find time to stand for a hand-colored portrait. In it, they carry the same expression of contentment and self-assurance found in August Sander’s portraits of Weimar-era bankers and bakers.

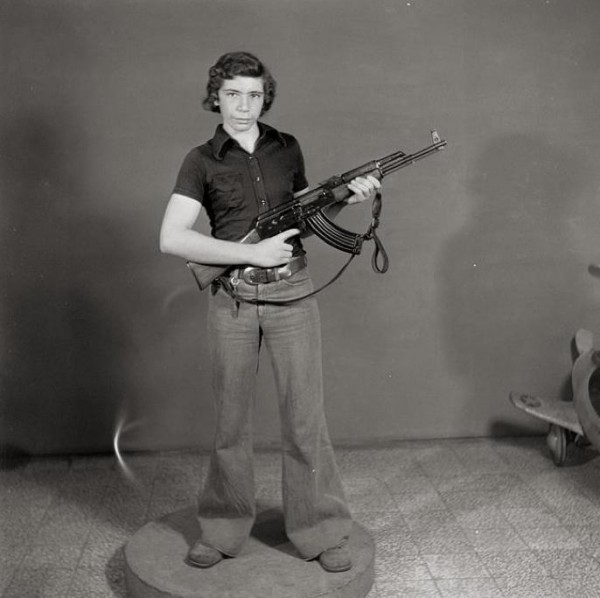

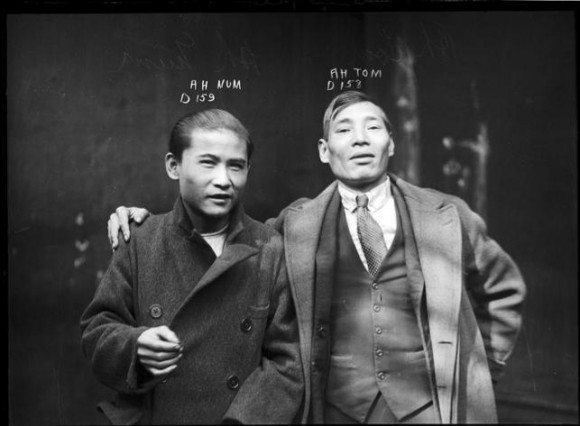

Ringo, a Palestinian resistant. Studio Shehrazade, Saida, Lebanon, 1948–53. by Hashem el Madani.

Collection: AIF/ Hashem el Madani. Copyright © Arab Image Foundation.

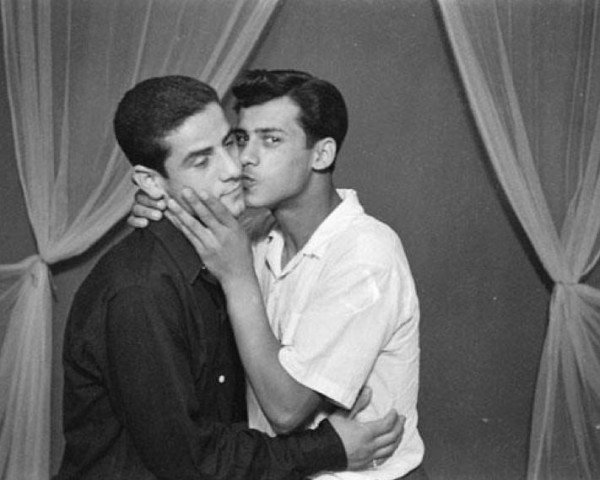

Madani preferred to pose his subjects in front of a light-colored sheet or gray wall. Sometimes, when he was working outside Sidon, he would use a backdrop of weathered wooden planks. In either case, the space of the photographs is constricted, private. Privacy was central to Madani’s business. The studio above the Cinema Scheherazade was a space apart, a place where people were freer than in the rest of their lives, if only incrementally. Madani photographed this freedom. The people in Madani’s pictures perform versions of themselves, exaggerated takes on their everyday selves. They pose with transistor radios and cardboard cut-outs of women from American advertisements. They dress up as cowboys and Bedouins, put on sunglasses and strip to show off their muscles. They wear keffiyehs, bell bottoms, and pork pie hats. Sometimes they bring guitars; much, much, more often, they bring guns. They flash the peace sign, play with bridal veils, and look sad that Nasser died. The militants do their best to look fierce; civilians play cops and robbers. Often, they kiss, but only members of the same gender: The women kiss women and the men kiss men.

Tarho and El Masri. Studio Shehrazade, Saida, Lebanon, 1955. by Hashem el Madani.

Collection: AIF/ Hashem el Madani. Copyright © Arab Image Foundation.

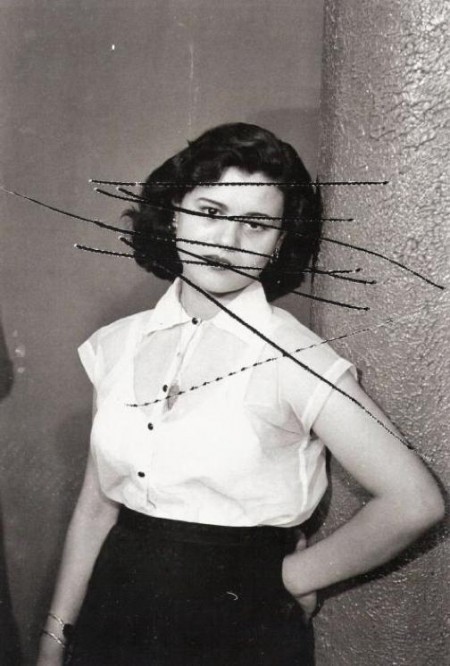

Sometimes, the freedom of the studio could be dangerous.Take the photograph below of Baqari’s wife (we do not know her name; he himself was a member of a prominent family in Madani’s part of Sidon). She must have snuck into Madani’s studio when her husband was away. According to Madani’s account, her husband, a jealous man, didn’t let her out of the house alone; he couldn’t stand for other people to look at her. She had two portraits taken. The first was a Bedouin fantasia: she wears a black abaya and a jeweled headdress and balances an amphora on her shoulder, which lets her show off the jewelry on her wrists. In the second one, she is a modern woman: her head is uncovered, and she wears a white blouse and black skirt. You can tell from the portraits that she wasn’t used to being looked at. She doesn’t confront the camera. Madani would tell his customers that he always focused his lens right into the eyes, right on the pupil. Did she shy away from this? She wasn’t sure where to put her hand. Madani must have told her to keep one arm akimbo, to show off her shoulders. Her expression is unreadable: it might be defiance, and it might be resignation.

Baqari’s wife. Studio Shehrazade, Saida, Lebanon, 1954. by Hashem el Madani.

Collection: AIF/ Hashem el Madani. Copyright © Arab Image Foundation.

When Baqari found out what his wife had done, he immediately went to the studio and demanded that Madani destroy the negatives. Madani refused, but he did agree to scratch across them with a pin instead. Years later, Baqari came back to the studio. By then, his wife had committed suicide, burning herself to death in order to escape him. He asked Madani to make prints from the scratched negatives; he wanted to know if there were any other negatives he didn’t know about. It didn’t matter if they were damaged. He just wanted to look at her again.

Hashem El Madani’s father, who came to Lebanon from Medina in Saudi Arabia, was once asked if photography was haram, or forbidden. He answered that it wasn’t; a photograph is just the same as a reflection of one’s face when one looks into a pond. Although the metaphor of the mirror has long been common to all kinds of photography, ever since Oliver Wendell Holmes described a camera as a “mirror with a memory,” it seems especially apt when applied to the work of portrait photographers. As an art, portrait photography is perhaps unique for the extent to which its practitioners have to subjugate their intentions to the desires of another. Studio portraitists provide a service. They perform to their clients’ expectations. Because of this, their work by nature tends to be modest; it whispers where others might shout. Its success depends to a great extent on the mood and inclination of its subjects. Beyond technical competency, a portraitist’s art surfaces in the ineffable quality of a style.

Most studio portraitists are forgotten — or remain anonymous. The few who are remembered were usually discovered towards the end of their lives or long after their deaths. The list of these masters is short. Besides Madani, it would have to include Mike Disfarmer of Heber Springs, Arkansas, E.J. Bellocq from the Storyville district of New Orleans, and Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé from Bamako, in Mali. All of them created bodies of work so vital a place, and an epoch, breathes through them. There may be many more such artists, but we don’t know their names.

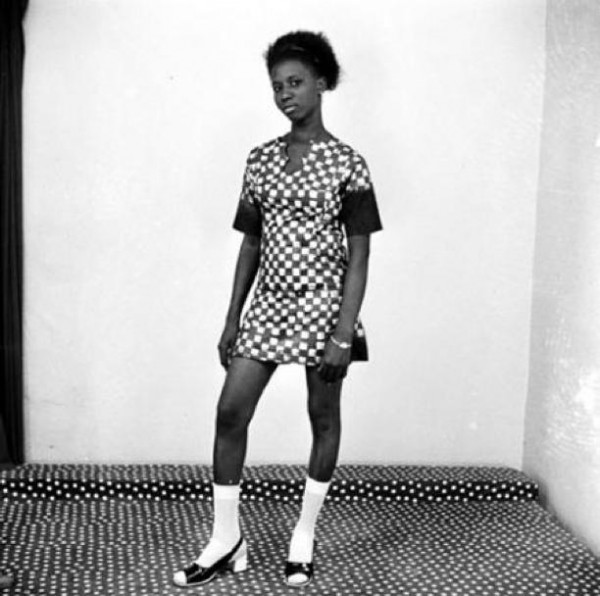

A portrait by Seydou Keïta.

A portrait by Malick Sidibé.

As individuals, these portraitists had little in common. Madani was a consummate professional, modest but hardworking, prominent in Sidon but unknown outside of it. Keïta and Sidibé, though, had somewhat similar backgrounds. Both came to photography from other professions, Keïta from carpentry and Sidibé from jewelry design, and both found success in Mali’s cosmopolitan capital, recording images of its confident, upwardly-mobile middle classes and the adventures of its youth. Their work has a grandeur that Madani’s lacks. Keïta especially knew how to imbue his subjects with a magnificent, nearly regal authority (this may have contributed to his appointment, in 1962, to the post of official photographer for the Malian government). Sidibé, who started out taking photographs of dancing club-goers in Bamako’s new nightclubs and street parties, remained more committed to sartorial flair and the idiosyncrasies of personal style.

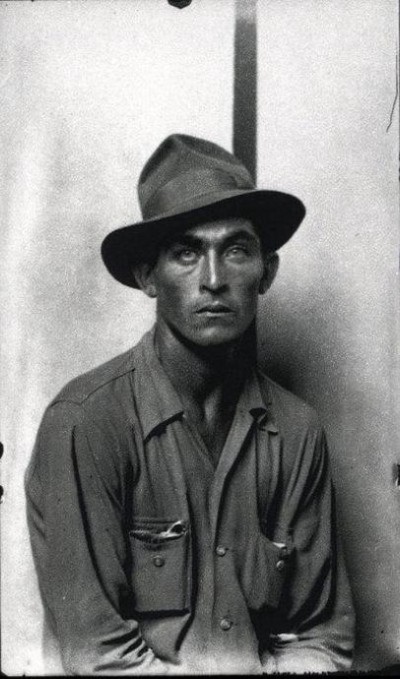

As for Disfarmer, his photographic style may have been plainspoken, in the vein of Madani, but he was nonetheless a true eccentric. Born Mike Meyer in 1884, he changed his name in middle age to register his contempt for the profession of farming (‘Meyer’ means dairy farmer in German) and to signal his critical distance from the citizens of the Arkansas mountain town where he worked. He kept himself aloof, dressing like a dandy and acting like a cipher. He claimed to have been deposited at his parents’ doorstep by a tornado. He built his first studio in the 1930s, after a real tornado destroyed his home and devoted the rest of his life to perfecting the portrait. One of his assistants said that no one could understand the workings of his mind, not even if they had a million years to think it over.

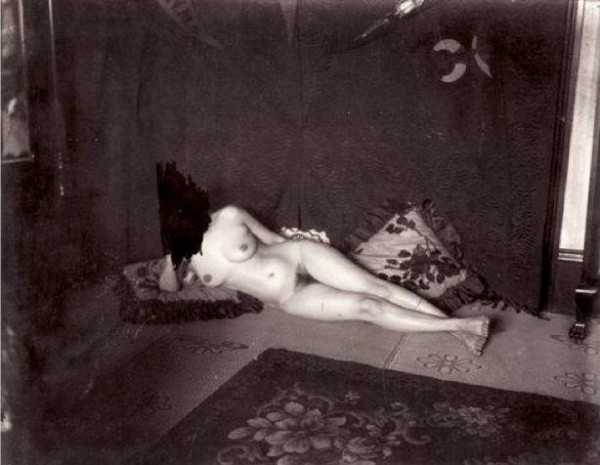

Bellocq may have been even stranger. He was another dandy, though the widespread rumors that he was hydrocephalic, or a dwarf, are probably untrue. Having grown up in a wealthy New Orleans Creole family, Bellocq came to photography as an obsessed amateur. With time, it turned into a career — he supported himself for a time as a commercial photographer for local shipping companies — but even his commercial work never lost that sense of having been made with the urgency of a private quest. Outside his job, Bellocq used his camera as a passport to the hidden regions of New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century. He took portraits of prostitutes from Storyville, the city’s legalized red-light district, and of opium dens in its Chinatown. All the photographs from this second series are lost, but 89 of the Storyville portraits survive. His relationship to the sitters he photographed is unknown — whether he was a voyeur, a lover, an interloper, or a friend is unrecorded. But the pictures seem to have been made for personal consumption. Some have argued that their aesthetic force comes not from art, but from the accident of circumstance; the photos were preserved as negatives (discovered and developed by photographer Lee Friedlander in 1970) and therefore had not yet been cropped into late-Victorian banality. This criticism seems to be missing something, though: in photography, mystery is a happy byproduct of ignorance, and beauty can be the result of chance.

New Orleans, Lebanon, Mali, Arkansas: the list of places these photographers worked are scattered pins around the globe (and what a shame that the lines between them can’t be filled in infinitely — think how great it would be if we had equivalent archives for Port-au-Prince, Cuernavaca, Muscat, Libreville, Palermo, and so on, ad infinitum).1 One of the great transformations wrought by the introduction of photography was that it democratized the portrait form, making it something that almost anyone could aspire to having. At the same time, however, Madani, Disfarmer, Keïta, et al. worked in a period when photography had not yet become routine. A single photograph could still fix a person for life, and for posterity, instead of acting, as they do now, as one more index of transformation over time. But this alone cannot account for the singularity of these portraitists’ images.

All of these studio photographers are notable for the degree of autonomy they grant their clients. They maintain a degree of restraint; the camera hovers in the middle distance between not too far and not too close. They fix a likeness without trying to wedge it to fit in a formal pattern. They do not elevate their subjects, as ceremonial photographs do, nor do they flatten them into components of a system of knowledge, as documentary photography tends to. Their work shares an openness, too; look through their archives and the mind has room to drift, to make connections between images across time and space.

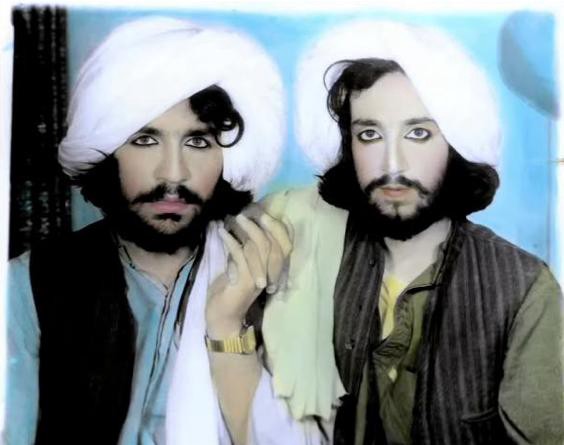

Madani’s portraits make me think of Tangier, where I once lived. They remind me of the dozens of photography studios I would pass each day on my way to work, all equally unremarkable, all featuring in their windows similar pictures of girls at their engagement, weighed down with titanic strings of amber beads in imitation of Touareg brides. Madani’s pictures of teenage militants send me to Olivier Assayas’ movie Carlos and the seductive ruthlessness of its protagonist. In front of Madani’s hand-colored prints, I think of the portraits members of the Taliban had taken of themselves in clandestine photo-booths.

The hand-tinting used here gives the mujahedeen and the Syrian intelligence agents alike a strangely sensuous air (look at the way their fingers interlock!), without robbing them their ferocity. They’re modern militants, killers maybe, but they also call to mind depictions of the Hindu saints.

In another direction, the scratches on the pictures of Baqari’s wife call to mind Bellocq’s nudes, the one where the faces have been erased, blotted them out until they appear as black voids.

These erasures are like bolts punched through the plane of the picture. No one knows why Bellocq did this, whether it was out of anger, jealousy, or shame. Some have suggested that it was done out of delicacy, to preserve the reputations of the women he had known, while others suspect the hand of his brother, a Jesuit priest.

Look at this girl photographed by Madani in Sidon in 1948 in the courtyard of a school. If I didn’t know she was Lebanese, I would assume she was from the Ukraine. Or maybe she could be the daughter of one of these women, both of whom are from Disfarmer’s Arkansas.

These two women are both posing with transistor radios; the woman on the left was photographed by Keïta, the one on the right by Madani. One might be tuning to a station in Beirut, the other, where — Dakar? Abidjan? Accra?

The props repeat and rhyme between the photographers. Keïta and Sidibé were both fond of posing people on motorbikes. This photograph is by Sidibé.

I love the contrast between the two men, one in traditional dress and one in bellbottoms and a cardigan, and I love the way they are seated: why does one face us while his friend smiles dreamily into the distance? Did Sidibé ask them to pose this way, or did he catch it as it happened?

Too often, we still treat photographs as if they were transparent communications, simply vessels of information, whether of the past, or of politics, or of an artist’s agenda. A great deal of contemporary art photography suits this attitude perfectly, employing the plain-style of vernacular portraiture for its own documentary ends. In these cases ( the work of Taryn Simon is a perfect example) the image always coexists with text. But this type of predetermined narrative limits what images can do; in support of a story or an agenda they gets emptied of their mystery, they fade out and go blank. By contrast, the most interesting photographs attack from the side. They make it difficult to tell where the line between the photographer’s objectives and the subject’s impulses is drawn. What was meant, and what was chance. Even so, we always think we know more than we do. We see dread or danger when it isn’t there, and miss it when it is. Look at these men.

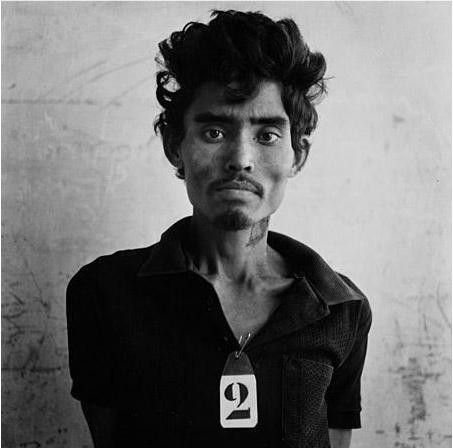

They are happy, because they are about to go free. Now look at this man — he is about to die.

His picture was taken by the wardens of the Tuol Sleng Prison in Cambodia, at the time a killing ground run by the Khmer Rouge. But without the number on his shirt, would we know?

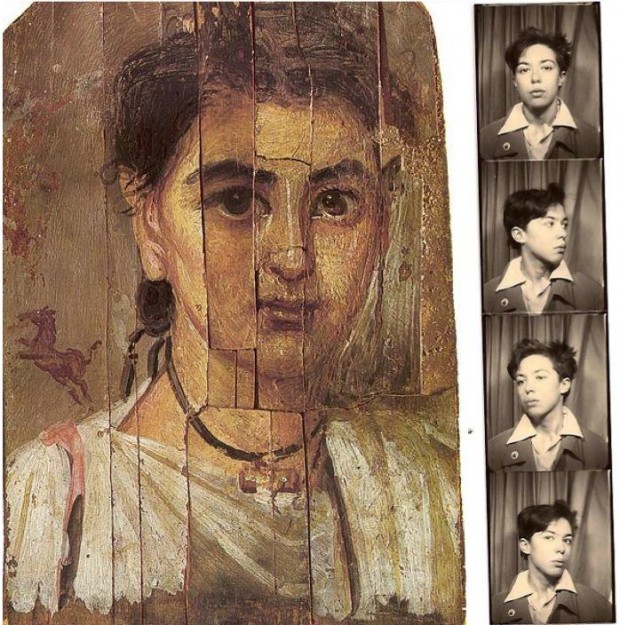

Since the publication of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, the equation of photography with death has become commonplace. Barthes argued that death is now ingrained in the texture of photography, and that it took up residence there after the decline of religion and the demise of ritual. In a similar vein, but from the opposite direction, Jean-Christophe Bailly, in a book on the Fayum mummy portraits, likens the photo booth to “a sort of provisional sarcophagus” where we go to know what it is like to be “ourselves, and nothing else but ourselves.” Is that what photo portraits are?

I like the idea of the provisional sarcophagus (though I’m not sure I understand it), but I like the analogy between the mummy paintings and portrait photography even more. The Fayum portraits are the earliest images of recognizable individuals that we have. Painted with colored beeswax on linen or thin planks of wood, they were made two thousand years ago for the residents of an Egyptian oasis town as likenesses of the faces of their beloved dead. Placed as a sort of mask on the head of the mummified body, the portraits served a dual purpose: as mementoes for the bereaved family (they were kept in the home, along with the mummy, for seventy days before burial) and as a means of identification for the dead on their journey to underworld. They were, in a genuine sense, passport photos to the afterlife. To us, they seem at once domestic and uncanny. The people in them seem uncannily present, as if just about to open their mouths. They face directly forward. Their gaze is insistent but nonjudgmental. In this, they share something of the neutral objectivity of modern ID pictures. John Berger registers the surprise of seeing them for the first time in one of his essays:

Imagine then what happens when somebody comes upon the silence of the Fayum faces and stops short. Images of men and women making no appeal whatsoever, asking for nothing, yet declaring themselves, and anybody who is looking at them, alive! They incarnate, frail as they are, a forgotten self-respect.

A declaration of life, and of a forgotten self-respect: this goes beyond Barthes’ notion of the portrait as a testimony and a figure of death. I think that this sense of self is what the great studio photographers were able to capture. Like the Fayum painters, they worked in obscurity. Their art was commercial and mundane. At the same time, it seems to participate in a great secret. Made to capture a transitory moment, these photographs nonetheless hold oceans of time. Like paintings on sarcophagi, they open onto eternity, and once seen, they can never be erased.

1 Of course, we do have something like it for Palermo, but of the dead: the newspaper photographs of Letizia Battaglia recording victims of the 1970s Mafia wars, collected in Letizia Battaglia: Passion Justice Freedom, Photographs of Sicily.

Related: NFL Films And The Magic Of Seeing Sports

Jacob Mikanowski writes about art, books and Europe east of Berlin. The Madani photos discussed here are in the collection of the Arab Image Foundation.