25 Days To Read "Cloud Atlas" Before Tom Hanks Ruins It Forever

I love David Mitchell and I love the essay he had in the Times magazine this past weekend about the experience of having his novel, Cloud Atlas, made into a movie. He writes about the way seeing a movie of a book changes the way we see the imagery of the book. And it made me very, very glad for my decision to have read Cloud Atlas this past month, before I see the movie that The Matrix-makers Andy and Lana Wachowski (and Tom Tykwer!) created out of it.

“Perhaps where text slides toward ambiguity,” Mitchell writes, “film inclines to specificity. A novel contains as many versions of itself as it has readers, whereas a film’s final cut vaporizes every other way it might have been made. Funny thing is, not even the author is immune to this colonization by the moving image. When I try to recall how I imagined my vanity-publisher character, Timothy Cavendish, before the movie, all I see now is Jim Broadbent’s face smiling back, devilishly. Which, as it happens, is fine by me.”

I’m glad that he’s happy with the way it came out. From what little I’ve read about him personally, he seems like a charming, down-to-earth guy. Everybody raved about the book when it was published six years ago, including two friends of mine whose taste in books I appreciate, and my wife, whose taste in books I also appreciate, and who knows my taste in books as well as anybody. But my wife (who reads five times as fast as I do, and so basically screens everything that comes out before I get to it) recommended that I not read it. She guessed that I would not like the way it jumps around in time and voice, taking on the styles of various literary genres (Azimovian sci-fi, Patrick O’Brien-style historical fiction, Elmore Leonard crime stories) or its overall theme, which is slightly spiritual and fantastical. She used words like “experimental” and “conceptual,” which are often red flags for me. (Because I’m such a close-minded, conservative jerk of a book reader, I guess.) So I gave it a miss, and felt okay about feeling left out whenever she and my other two huge-Cloud-Atlas-fan friends would get together and gush about it.

Then, a couple years later, she read another David Mitchell book, Black Swan Green, and immediately upon finishing the last page, said, “You have to read this. You will love it.”

I was almost finished with the book I was reading (Cormac McCarthy’s No Country For Old Men, which I thought was totally excellent — and in fact, since we’re on the subject of the nexus of books and movies, read more like a movie to me than any other book I’ve ever read. Probably relatedly, the movie the Coen Brothers made out of it is the most faithful film adaptation of a book I’ve ever seen.) So I picked up Black Swan Green and read it over the next couple of days. (It’s short and reads quickly.) And, yes, sure enough, loved it very much. Part of that love spurred from the fact that I am about the same age as David Mitchell, and so was about the same age as the main character in Black Swan Green, who was “coming of age” in the book, set in 1983. The book is apparently semi-autobiographical, and so that means that David Mitchell grew up in a place similar to where I grew up, the suburbs, at the same time I was growing up there, and thought about things in much the same way that I thought about things. (Probably in much the same way that lots of 13-year-old suburban boys think about things.) Because reading that book was one of those times that made me feel like someone had been spying on my memory without my ever knowing it, and then transcribed the thoughts with uncanny accuracy. This happens with the best books, right? The “Oh, man, that’s exactly the way I feel! Why didn’t I write that?” thing. It happens more with books than movies, I think, something that has to do with a novel containing as many versions of itself as it has readers, as Mitchell said. The slide toward ambiguity makes it easier for us to graft our specific experience of the world atop the writer’s version. (Or vice versa.) But it can happen with movies. Watching Donnie Darko for the first time was like that for me, too.

Anyway, I loved Black Swan Green so much, and was so impressed with my wife’s prognosticative ability, that I figured she must be right in predicting that I would not like Cloud Atlas. So I still didn’t read it.

A few years after that, Mitchell published his next book, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet, and my wife read it and was absolutely doing back flips about it. I think she might say this is her favorite book written this century or something like that. I would imagine it’s on her Top 10 list, all time. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet is a love story set at a Dutch East India Trading post in late-18th-century Japan. This sounds about as far from any book I would ever pick up as any description of any book I’ve ever heard described. But, man, did she love it! She started talking about how David Mitchell might be her very favorite author and all that. So, since, I loved Black Swan Green so much, and since my wife, whose taste I appreciate so much, apparently loves everything David Mitchell writes, and I’d always heard all these other people talk about how Cloud Atlas was such a masterpiece and all, I got to thinking maybe I should take a crack at it.

But I never did. There are always too many other books to read.

A couple months ago, I learned about the movie that they were making about it. And besides thinking, how will they make a movie out of this experimental, conceptual book that I know weaves several different stories across several different centuries?, I also thought that I better read it right then. Because if I saw the movie, I would certainly never read it after that. I don’t think I’ve read a book after having seen a movie version of the story. It seems sort of like an impossible thing. Both for reasons of needing the suspense of not knowing the plot to pull me along, and also because of what Mitchell talked about in his essay: I like to imagine a book’s scenes in my head, the way the words make me imagine them, not how someone else interprets them.

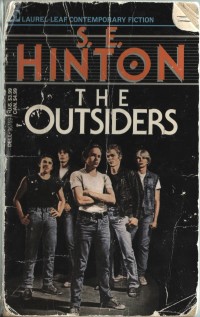

I just had a conversation with a couple of kids about this last weekend. They’re eleven and thirteen, and I’m friends with their dad Mark, and I asked them what their favorite books and movies were, and they both mentioned The Outsiders, both S.E. Hinton’s book, and the movie that Francis Ford Coppola made out of it with Ralph Macchio and Matt Dillon. That book was a favorite of mine when I was a kid, too. Seeing the movie of it was one of the great moments of cultural betrayal of my young life. In the book, the character Dallas, or “Dally,” was described as having “small, sharp animal teeth,” and hair “so blonde it was almost white” and eyes that were “blue, blazing ice, cold with a hatred of the world.” I imagined him as nearly albino. And thin and lanky and wounded-looking. And this look, his shocking, sort of ghostly appearance, with its hints of inbreeding, became a big part of my understanding of his character. His psychic wounds came in part from looking so different from everyone else, so unhealthy, this was part of his outsiderness. But then in the movie, they cast Matt Dillon as Dally. Brown-haired, brown-eyed, super-handsome Matt Dillon! And they didn’t even bleach his hair blonde! If kids had said “WTF?!” back in 1983, I definitely would have said that. (I wonder if David Mitchell would have, too. I bet he would’ve.) I was furious. This didn’t make any sense, and it really robbed something from me that I’d found in the book. I explained this to Mark’s kids, and they agreed, but they were not as upset by it as I was, and, apparently, sort of still am. They’re pretty well-balanced-seeming, Mark’s kids. I think they might have even seen the movie before reading the book, somehow. I don’t know how. But they were like, “Oh, yeah, Dally did have blonde hair in the book, didn’t he? Huh.”

The case with Cloud Atlas is even worse, or at least, more fraught. Because, thinking back, despite how wrong his hair looked, Matt Dillon was actually really good in The Outsiders. He defined a different Dally than the one that I had known, but it was not a worse Dally, I don’t think. (It may have been a more sympathetic one, and so therefore less complex, so maybe that’s not so great. But I don’t know. It was a long time ago.) Indeed, Matt Dillon’s version of pouty emotional woundedness came to represent the essence of all of S.E. Hinton’s work on film, didn’t it? And I don’t think that is so bad, is it? Matt Dillon has gone on to become a real favorite actor of mine. (He was so great in Wild Things!) But Cloud Atlas happens to be starring Tom Hanks. Tom Hanks. Tom Hanks! Now, of course I loved Tom Hanks in “Bosom Buddies” and “Family Ties” and Bachelor Party and Nothing in Common with Jackie Gleason (especially Nothing in Common with Jackie Gleason) and Splash and all that. But then he became so Tom-Hanks-America’s-Favorite-Nice-Guy-Superstar around the time of A League of Their Own and Sleepless In Seattle. And Philadelphia, which, I admit to thinking he was very good in, but still. And then Forrest Gump happened, and everybody started talking in that horribly annoying mentally-disabled way he did in that movie, and I saw the movie, and I’m so sorry I did, because it makes you want to puke in your shoes and wash your eyes out with lye, but it won’t work. You can never unsee something like that. And then I remember seeing a full-spread two-page ad in the Times one day which showed him in that dumb white suit, and they’d made a huge American flag out of all the stars that different reviewers at different newspapers and magazines had given the movie. And it said something to the effect of, “AMERICA AGREES: FORREST GUMP IS THE MOVIE OF THE SUMMER! GO SEE IT AGAIN BECAUSE EVERYONE ELSE IS GOING TO SEE IT OVER AND OVER AND AGAIN.”

I remember seeing the ad and feeling more like I was living in a fascist, totalitarian state than I’d ever felt before. Fair to the man himself or not, I swore that day that I would never watch another Tom Hanks movie, ever.

(I have since broken that vow, I’m ashamed to say. I saw Apollo 13, and Saving Private Ryan, and Cast Away, which was good until Tom Hanks started talking, and — this really messed with my mind — I even really strongly very much liked a Tom Hanks performance, in The Road to Perdition. Nothing’s as simple as you want it to be, not even disdain.)

But still. Reliably vacillating between over-earnestness and simpering. Remember when he broke the fourth wall and gave the camera a gleaming little half-wink at the end of the trailer for Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close that was, in its context, so disgusting and shameless in its manipulation and exploitation of 9/11? That’s the second thing that, even though it probably wasn’t his fault, I’ll never forgive Tom Hanks for. (Well, maybe the third. I’ve never The Green Mile. But those trailers were traumatic, too.)

Soon, many of us, like David Mitchell himself, will be never be able to envision a host of the characters from Cloud Atlas as looking any other than like Tom Hanks, because, as we know from the movie trailer, he’s playing more than one of them. It’s not too late, though! The movie itself doesn’t come out until the 26th. Here’s the trailer. Don’t watch it if you have not yet read the book.

My wife, it turns out, was wrong. (Something that happens less often in our house than would be optimal.) I enjoyed Cloud Atlas very much! I didn’t find it pretentious or experimental or anything like that. Well, one part tells a story through an interview, but it’s not at all off-putting. And another part employs a heavy pidgin English that seems a bit strong, a bit too much like Uncle Remus at first, but once you get your bearings, it’s not so bad. If anything, actually, I would think its one of the more accesible books I’ve read in a while. It’s basically six different stories that take place at six different times, in six different places in the world, told in six different voices. But all of them are told relatively straightforwardly, and in unusually beautiful prose. The “Russian-doll” structure that people talk about a lot is novel (hey!): five of the stories are broken in half, and arranged leading forward in time up to the middle, and last story, and then backwards in time til the end of the book. But just the order of the stories, not internally within each. It’s not like Memento, or 21 Grams or that episode of “Seinfeld” when they go to India for the wedding.

The way the stories come together and reflect off each other, loosely, subtly, abstractly. More thematically, I guess, than anything else. (Unless I missed something, which is always possible.) It’s great, I’m telling you. (I’m probably not the first person to have done so. It’s a very popular book.) In fact, it’s a book that I have a hard time imagining anybody not liking. It’s action-packed and suspenseful. It’s got a little something for fans of all different types of books to like, and not a lot not to like. (I know one person that disliked it, who read halfway through and put it down. I have not yet talked to her enough about why. I think she got turned off at the start of the pidgin English part, and gave up too early.) It actually reads a lot like a movie, in the way that No Country For Old Men did. Well, it reads like six movies — which would seem to be the challenge of bringing it to the screen in under twelve hours. That’s one of the reasons I’m interested in seeing it. To see how they cut it down and put the pieces together. (Even when I know I’m bound to be disappointed. Curiosity vaporized the cat’s literary experience.)

I’m left perplexed by why my wife guessed I wouldn’t like it. You think other people know you. But they don’t. Not even your wife. No one knows anybody, really. Not that well. We’re born alone and we die alone, and we read books alone. You can watch movies with other people. And laugh or cry along together, or sneer and jeer and groan together. (In whisper voices, one would hope, if you’re in a theater. Just because there’s no God doesn’t mean we should be impolite.) I guess that’s one benefit of having the pure, mind’s-eye experience of reading colonized by the moving image. Laughing aloud with a bunch of other people in a crowded theater, many of them strangers, is one of the great pleasures of modern life, one of those times when we’re reminded of the ways in which we’re not totally alone, one of the bridges that connects us to other people and lets us know how much they’re like us. It wouldn’t be possible without the colonization. As text’s slide towards ambiguity allows for a more personal, intimate experience, film’s inclination to specificity opens it up for shared, universal experience.

Real-time communal experiences are not the only things that open up such bridges, though. The same miracle (or, as you may choose to think about, pleasant delusion), can happen through solitary endeavors, too. That feeling that I got that David Mitchell was spying on my thoughts — that serves as that same kind of bridge, too. And in so, reading ceases to be a solitary experience. And one that achieves a sort of loophole in the time/space continuum.

Or even just in talking to people, sharing ideas, about books and movies, say. Any time we feel like we honestly understand or sympathize with something someone else is saying (something that happens all too infrequently, considering how frequently its opposition carries the day, and how awful and lonely that feels.) Maybe that’s happened to you, at some point over the past six or seven hours it’s taken to read this blog post. Maybe you had that same feeling when you saw that Forrest Gump ad in the New York Times 18 years ago, and made the same promise to yourself, and then broke it. And are now feeling even the slightest bit warmed by the thought that I have been right there with you. In guilt and shame. It is my loftiest hope that this might be the case.

In the absence of faith in God, sharing ideas with other human beings in the only thing that pops the existential bubble wherein we spend most of our time. Even just for a moment, before they seal us up again in our essential solipsism.

(I guess when you take drugs you can get that feeling of communion with a dog or a tree or a patch of moss or the sky or the whole universe. That can be nice, too. But, again, it’s always fleeting.)

So hurry up and read Cloud Atlas, is what I’m really saying, before you see Tom Hanks stink it up, coming incredibly soon and surely quite loudly, in theaters nationwide.