Our Dreamer in Chief

Barack Obama and the stories he told.

If you’d written it up that a man, descended from slaves, the product of a single parent home and an heir of Chicago’s South Side, would not only graduate from that country’s preeminent institution of law, but become the first black editor of its preeminent publication; only to later harness the reigns of a senatorial seat, and ascend to its country’s highest elected position for dual terms, then that notion, your plot, would be deemed unlikely at best. An editor might point to your protagonist, thumbing at his glasses, frowning, mouthing the syllables in their entirety — Barack?

From Paul Beatty’s Gunnar Kaufman, to James Baldwin’s John Grimes, to Junot Diaz’s Oscar Wao, America had no shortage of narratives of “childhood, the conflict of generations, provinciality, the larger society, self-education, alienation…and a working philosophy,” (Jerome Hamilton Buckley, Season of Youth.) Obama’s public legacy is a genre in itself. In cultivating his very American narrative, he rebranded the country’s approach to its own journey, and the public’s faith in that relationship. He believed that we believed.

Obama’s faith in story, and his faith in his constituency’s faith in story, allowed him to approach our country with possibility. He (still) holds his hopes in our hope in ourselves. In a conversation with Michiko Kakutani, he described the revelation of connecting narrative with public service:

I was hermetic — it really is true. I had one plate, one towel, and I’d buy clothes from thrift shops. And I was very intense, and sort of humorless. But it reintroduced me to the power of words as a way to figure out who you are and what you think, and what you believe, and what’s important, and to sort through and interpret this swirl of events that is happening around you every minute… The great thing was that it was useful in my organizing work. Because when I got there, the guy who had hired me said that the thing that brings people together to have the courage to take action on behalf of their lives is not just that they care about the same issue, it’s that they have shared stories. And he told me that if you learn how to listen to people’s stories and can find what’s sacred in other people’s stories, then you’ll be able to forge a relationship that lasts.

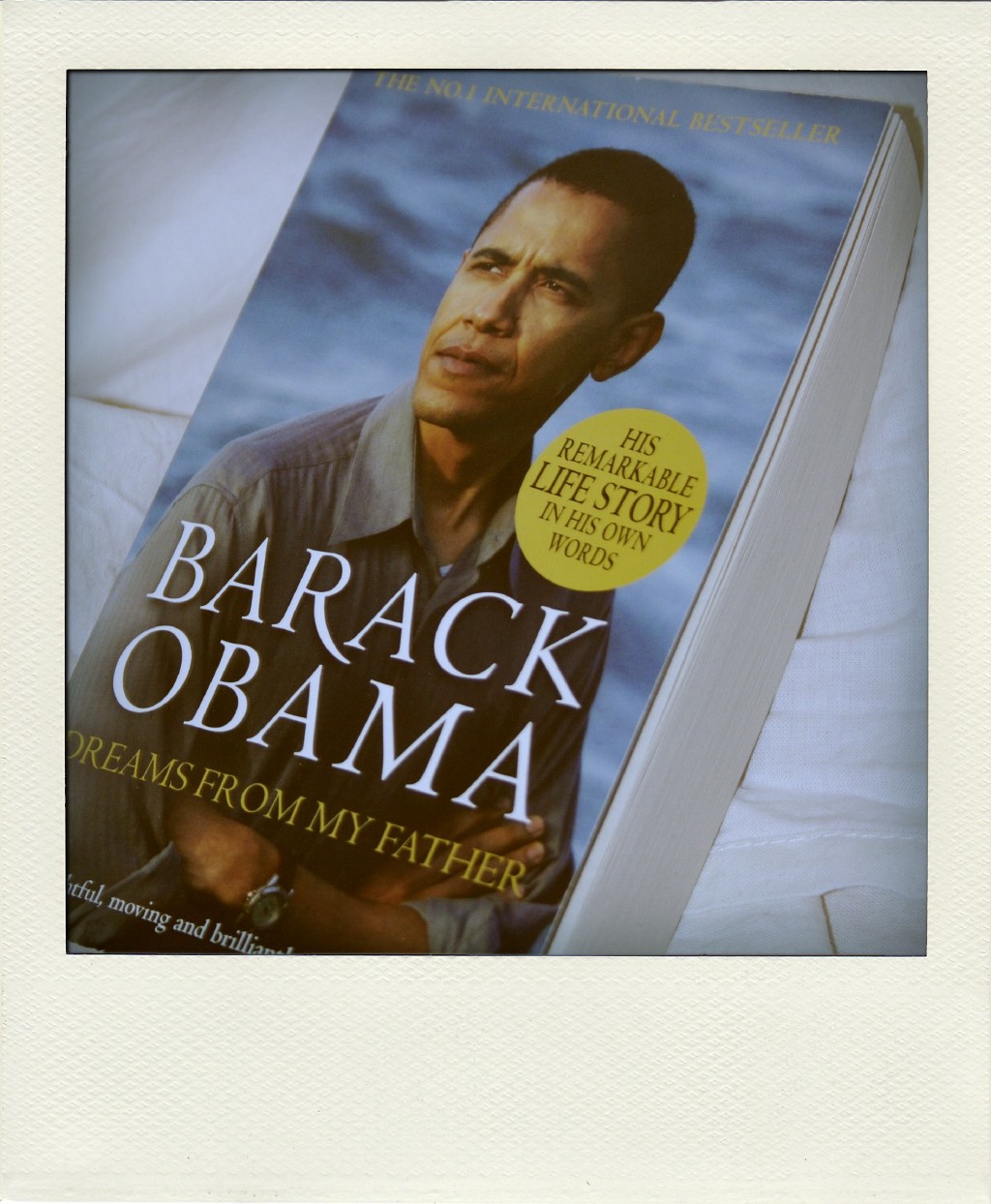

Years later, he’d defer to our collective stories in 1995’s Dreams From My Father:

Our sense of wholeness would have to arise from something more fine than the bloodlines we’d inherited. It would have to find root in Mrs. Crenshaw’s story and Mr. Marshall’s story, in Ruby’s story and Rafiq’s; in all the messy contradictory details of our experience.

And it was a notion he repeated in his final major speech as the first black president of the United States of America, quoting Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird:

You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.

But throughout his presidency, Obama’s hope in narrative was caricaturized and flattened. It was mystified, overhyped, ridiculed, and praised. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, her characters approached it as slightly unbelievable:

“He just makes me feel good!” Marcia said, laughing. “I love that, the idea of building a more hopeful America.”

“I think he stands a chance,” Benny said.

“Oh, he can’t win. They’d shoot his ass first,” Michael said.

“It’s so refreshing to see a politician who gets nuance,” Paula said.

While in Teju Cole’s Open City, the narrator’s relationship to an individual’s direction felt more tenuous:

Each person must, on some level, take himself as the calibration point for normalcy, must assume that the room of his own mind is not, cannot be, entirely opaque to him. Perhaps this is what we mean by sanity: that, whatever our self-admitted eccentricities might be, we are not the villains of our own stories. In fact, it is quite the contrary: we play, and only play, the hero, and in the swirl of other people’s stories, insofar as those stories concern us at all, we are never less than heroic.

In an essay for The New Yorker, Cole actually approached the pitfalls of that allegiance to narrative, and how Obama’s presidency may have cauterized it, turning him inside out of himself:

How on earth did this happen to the reader in chief? What became of literature’s vaunted power to inspire empathy? Why was the candidate Obama, in word and in deed, so radically different from the President he became?… I wonder if the Presidency is like that: a psychoactive landscape that can madden whomever walks into it, be he inarticulate and incurious, or literary and cosmopolitan.

The president’s relationship to story wasn’t limited to a particular political agenda. The notion was awe-inspiring, and no less alluring to any number of storytellers. The New York Times runs a series of author interviews entitled “By The Book”, and among the column’s questions was an exploratory one: if you could require the president to read one book, what would it be? Some interviewees towards the president’s advocacy (Louise Erdrich called Obama “an extraordinary advocate for Native Americans”, recommended Jaimy Gordon’s Lord of Misrule), while other acknowledged the president’s reputation as a bookworm (Jacqueline Woodson said that Obama and the First Lady had “probably read anything I’m just learning about”), while other authors dared to look forward, past the Obama presidency (Daniel Alarcon quipped that it “depends entirely on which president you’re speaking of. Obama? Whoever succeeds Obama? Their suggested reading lists might be so different as to exist in different wings of a very large library”).

And perhaps that last bit, as much as anything else, is what makes his successor’s prospects so damning: the absence of hope in his story. A rejection of hope in his narrative. After Obama, this is not simply striking, it feels absolutely unacceptable. Because, for many of us, an allegiance to narrative is what we came up on. We cannot imagine a world without it. A world without it is no world to live in. It’s a conclusion the protagonist of our country’s most famous bildungsroman reached:

That’s the whole trouble. You can’t ever find a place that’s nice and peaceful, because there isn’t any. You may think there is, but once you get there, when you’re not looking, somebody’ll sneak up and write “Fuck you” right under your nose.

Most working and middle class white Americans don’t feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race. Their experience is the immigrant experience — as far as they’re concerned, no one’s handed them anything, they’ve built it from scratch… So when they are told to bus their children to a school across town; when they hear that an African-American is getting an advantage in landing a good job or a spot in a good college because of an injustice that they themselves never committed; when they’re told that their fears about crime in urban neighborhoods are somehow prejudiced, resentment builds over time.

That was Obama speaking in the midst of the 2008 election. He hadn’t received the Democratic nomination yet, and Reverend Jeremiah Wright had just tanked his sail. But Obama praised him even so, just like he praised everyone else, and what felt like a ploy at the time proved to be an indelible part of his ethos. Instead of damning the rationales of racists and misogynists and homophobes, or exploiting their motives, or urging them to catch up with the globalized West, Obama diminished logic from the equation. He turned to nonjudgmental tropes. He told a story free of villains, or winners and losers. In the story Obama told, you weren’t garbage for disagreeing with him — your views were simply a product of your narrative. He strove to tell his in a way that had room for you, too.

It’s possible that we won’t live to see the rise of another black president. But when Obama told us, all of us — the canvassers and the DREAMers and the doubters and the seniors and the soldiers and the gays and the racists and the Christians and the Mormons and the Moroccans and the Mexicans and anyone else who was willing to hope — that he really, truly, believed in us, and in our stories, we couldn’t help but believe him, because he believed it so ardently himself:

Show up. Dive in. Stay at it. Sometimes, you’ll win. Sometimes you lose. Presuming a reservoir of goodness in other people, that could be a risk. And there will be times when the process will disappoint you. But for those of us fortunate enough to have been part of this work and to see up close, let me tell you — it can energize and inspire. And more often than not, your faith in America and in Americans will be confirmed. Mine sure has been.

That, I think, was the take-away. That we be here. That we be present in the moment. The narrative — our narrative — can get away from us if we let it, because every society’s inevitability is an illusion, and if we do not take hold of our individual storylines one day we’ll look up and they’ll be gone.