Chicken With Ball Bearings: How To Cook Like A Futurist

Chicken With Ball Bearings: How To Cook Like A Futurist

by Willy Blackmore

After years of disavowing the unwanted, unloved phrase “molecular gastronomy,” the culinary avant-garde was gifted in 2010 with a new umbrella term under which to gather: Modernist cuisine. The name came from Nathan Myhrvold, whose five-volume doorstop of a cookbook of the same title offers both a history of culinary thought and detailed descriptions of the techniques and recipes pioneered by the likes of Ferran Adrià and Heston Blumenthal. (A shorter version is due out in October.)

Before diving into the proverbial immersion circulator, Myhrvold turns to art history to make the case for the title Modernist Cuisine. Writing on the artistic advancements of the Impressionists, Myhrvold expresses admiration for the group’s determination to do away with tradition in pursuit of an art that more accurately reflected modern life. But Myhrvold is less approving when it comes to the artists’ eating habits. He contends that the diets of the “cultural revolutionaries who launched these movements,” the Impressionists and the other Modernists that followed them, were unfitting of their artistic character, consisting only of “very conventional food.” After stating, incorrectly, that Modernism “never touched on cuisine,” Myhrvold goes on to claim that his cohort is doing what he believes the avant-garde of the 20th century failed to: Extend Modernism to the culinary realm.

The former Microsoft executive has clearly not devoted enough time to his art-history reading. It’s difficult to believe that he never bumped into the imposing figure of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of the Futurists, Italy’s aggressively right-wing art movement that worshipped technology as well as war.

The Futurists made paintings, sculpture, poetry and music — and they tackled the culinary world as well. In 1932, Marinetti published The Futurist Cookbook, an extended manifesto that railed against technologically antiquated kitchens, International-style cuisine and, above all else, pasta, a food Marinetti hoped to abolish from the Italian diet. In Futurist thinking, the empty calories of spaghetti were an impediment to a quick-moving modern life, the collective dead weight of so many plates of pasta sitting in the nation’s stomach holding Italy back from advancing into the brave new technological world. At Futurist-friendly restaurants, Marinetti suggested that the waiters would tell patrons that “we have come to this decision [to ban pasta] because pasta is made of long silent archeological worms which, like their brothers living in the dungeons of history, weigh down the stomach make it ill render it useless. You mustn’t introduce these white worms into the body unless you want to make it as closed dark and immobile as a museum.”

Marinetti proposed a complete rewriting of Italian food traditions, a new cuisine influenced by science and unencumbered by tradition — culinary Modernism, by another name, an approach to cooking that has Ezra Pound’s command to “make it new” at its mechanized heart. Marinetti wrote that the new cuisine, “tuned to high speeds like the motor of a hydroplane, will seem to some trembling traditionalists both mad and dangerous.”

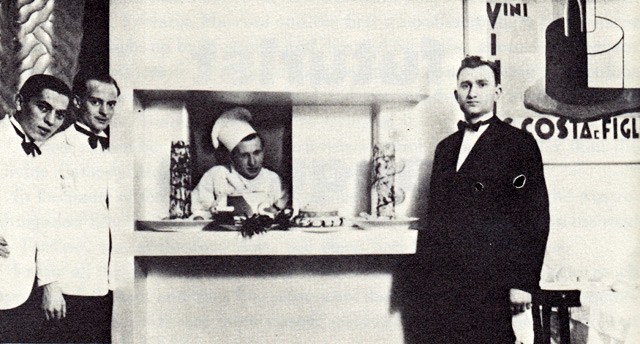

At the Holy Palate restaurant in Turin.

Out of the kitchen went quiet, hearthside domesticity. In came the Machines. The Futurist kitchen Marinetti envisioned was an extension of his proto-bro obsessions with cars and guns and airplanes. Countertops would be lined with ozonizers, ultra-violet ray lamps, electrolyzers and colloidal mills, the cutting board jockeying for space with centrifugal autoclaves and dialyzers. The electrolyzer would be employed “to decompose juices and extracts, etc. in such a way as to obtain from a known product a new product with new properties.” All of this decades before Pacojets and immersion circulators and iSi siphons would become fetish objects of the kitchen. Marinetti’s kitchen, more a vision than a reality, was really a list of possibilities rather than detailed uses. The technology could be employed to improve nourishment (Marinetti was obsessed with nutrition and, along with his anti-pasta vitriol, rails in the cookbook against processed grains, eating too much meat, and robbing vegetables of their healthfulness by overcooking) or to perfectly balance acidity and alkalinity, salt and heat. Less practical electric dreams include Marinetti’s desire to make foods taste and smell of ozone, or to run drugs through that colloidal mill.

Marinetti surely would have approved the technological approach to cooking promoted in Modernist Cuisine, but in terms of breaking with the status quo, of making it new, Myhrvold’s cookbook has little to offer. His rebellion has more to do with better-living-through-technology takes on familiar, traditional dishes such as burgers or pad Thai; deconstruction and nostalgia, those well-established tropes of postmodernism, play a significant role. Sit it next to the unhinged inventiveness on display in The Futurist Cookbook, and I find myself preferring the company of the crew of warmongering Fascists.

But what about the food? There are actual recipes in the book, buried in the final pages under the title “Futurist Formulas for Restaurants and Quisibeve.” You can learn to cook Futurist Risotto with Cape Gooseberries or The Soil of Pozzuoli and the Greenery of Verona, which involves chewing candied citrons stuffed with fried cuttlefish “as if they were anti-Futurist critics.” But Marinetti devotes far more of his writing to recounting Futurist banquets and dinners at The Holy Palate Restaurant in Turin, where his culinary ideology was put into practice. The centerpiece of most of these meals was Sculpted Meat, a tower of veal stuffed with vegetables, honey dripping Karen Finley-like down its side, toward the base of sausages and “three golden spheres of chicken meat.” Envisioned by the painter Fillìa as a “symbolic representation of all the varied landscapes of Italy,” this veal tower is repeatedly referred to by Marinetti as the cornerstone of Futurist cooking.

A Futurist banquet in Tunis. Marinetti is standing in front.

Tactile and scent components accompanied other dishes, an encouragement to diners to use all of their senses. In one such dish, a salad of fennel, olives and candied fruit is accompanied by a small rectangle containing various textured materials. While eating the foods, the diner “delicately passes the tips of the index and middle fingers of his left hand … a swatch of red damask, a little square of black velvet and a tiny piece of sandpaper.” Sound and a heightened level of scent are introduced into the experience too: “From some carefully hidden melodious source comes the sound of part of a Wagnerian opera, and, simultaneously, the nimblest and most graceful of the waiters sprays the air with perfume.” Another dish, Chickenfiat, featured the very taste of industry itself: Steel. The flavor is delivered by a handful of ball bearings tucked into the bird’s shoulder, a simple act of seasoning that turns this dish into the ideal synthesis of Futurist ideas about advancement in technology (the more, the bigger, the better) and the development of culinary arts that “eschews plagiarism and demands creative originality.”

Politics and pasta fall away in the “Definitive Futurist Dinners” section of the book, which consists of short prose-poem-like “recipes” for different meals. Reading more like Yoko Ono’s instructional paintings than Julia Child, these “definite Futurist dinners” are more artistic in terms of the prose itself, and largely devoid of Marinetti’s grandiose manifesto tone.

One that cuts close to the heart of the Futurist ideal — the perfect union of life and art and technology — takes place in the cockpit of an Autostabilizing DeBaernardi airplane flying 1000 meters above the Italian countryside. Within those curved steel walls, decorated with Futurist “aeropaintings,” lobsters are prepared. After being boiled, “electrically,” in seawater, the meat is removed and the shells, tinted blue with methylene, are stuffed with a “pulp of egg yolk, carrots, thyme, garlic, lemon rind, the eggs and liver of the lobsters, capers” and sprinkled with curry powder. But rather than eating the shellfish, “the diners, holding in their fists little ceramic bell-towers full of Barolo mixed with Asti Spumante, eat villages, farms and fields speeding by.”

How could similarly seasoned lobster, cooked sous-vide, ever compare?

Willy Blackmore is the Los Angeles editor of Tasting Table. He is not a Fascist.