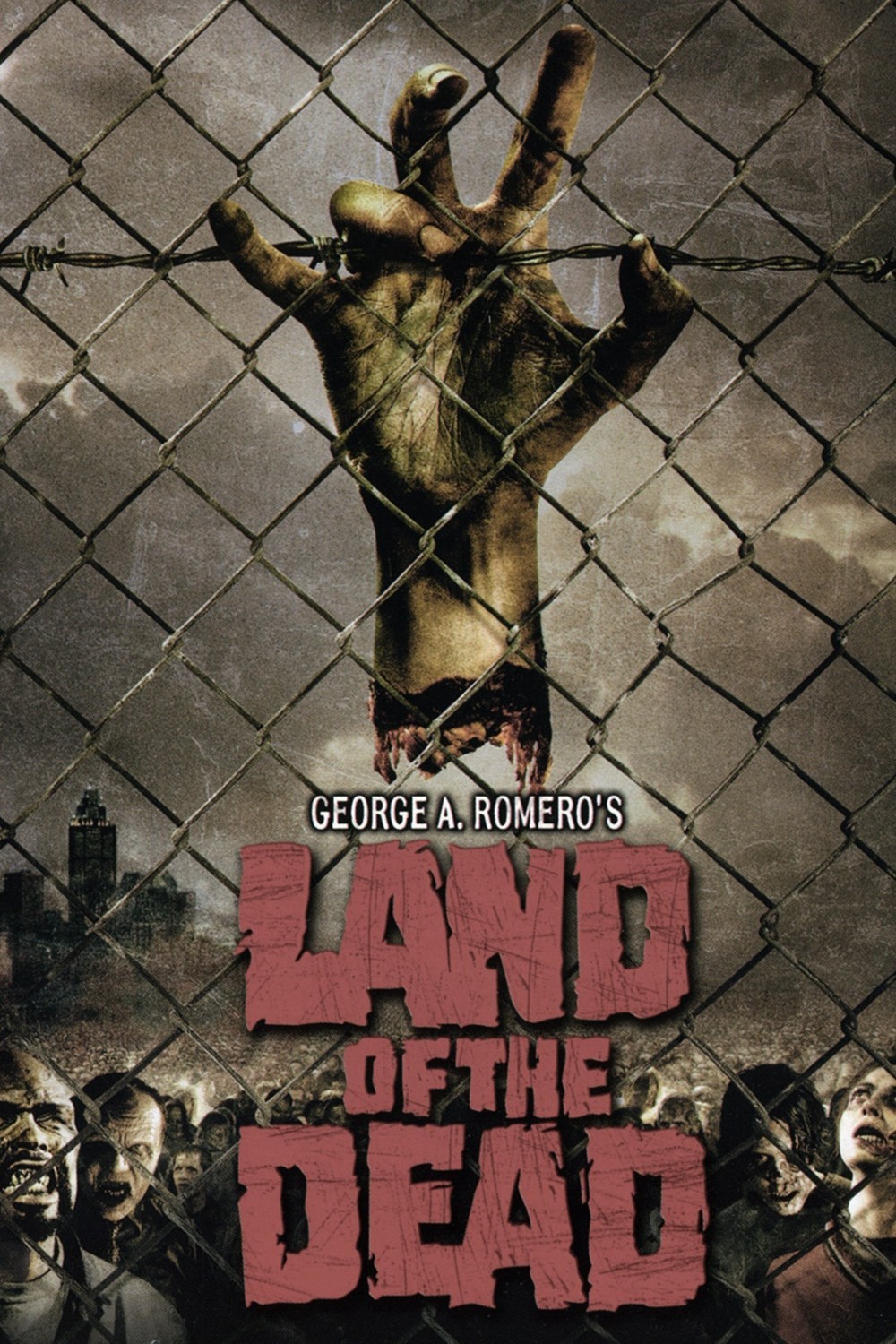

The Revolutionary Hope of George Romero's 'Land of the Dead'

It’s less celebrated, but worth revisiting

When the obituaries for director George A. Romero — who died on Sunday, at age 77 — came out, the credits mentioned were rightfully obvious. Here lies the renegade director who invented the zombie genre with Night of the Living Dead, then Dawn and Day of the Dead. But what’s missing in the obits is praise for the most underrated entry in his zombie oeuvre: 2005’s Land of the Dead.

It’s his only zombie movie with any “star power,” (including Simon Baker, Asia Argento, John Leguizamo, and Dennis Hopper), but it’s also his only zombie movie — and one of the few in the whole genre — that take place in the world after the outbreak. Humanity has regrouped from the shock; they’ve gotten used to it. They know how to kill them, they’ve fortified safe areas, even captured a few for entertainment, like target practice or, “take your photo with a zombie” shlock. Also returning into our pieced-together world? Our good old friend, class dynamics.

Most of the film takes place in downtown Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle, a zone made zombie-free by protection from two rivers and one heavily barricaded front. The city is an extended shanty-town — complete with end-of-the-world preachers, campfires, even a minimal puppet theater. The one notable exception: Fiddler’s Green, the lush high-rise presided over by Paul Kaufman (Dennis Hopper) in a quasi-feudal king role. While outside there is hunger and disease, behind the complex’s hired security force, the ruling elite live in luxury. Soft music plays, fountains drone their contemplative patter, “Greenies” window-shop at the season’s latest fashions. It’s an elite circle everyone wants to get into, but space is very limited.

But the city has basic survival needs — they’ve already raided the downtown grocery stores, and there’s no room to grow crops. Enter the “raiding parties,” city-sanctioned teams allowed outside the city gates to retrieve needed items.

Viewed through the lens of Marxism (because why not), those in the Green are the bourgeoisie, while those in the shantytowns are the proletariat. There’s a small group of revolutionaries living in the shantytown, whispering about overthrowing Kaufman’s reign (“he kept the best for himself and left a slum for us,” says a rabble-rouser with an Irish accent, “if all of you would join up, we can make this a fit place to live in!”). What’s kept them in place? Guns and money, sure. But more than that, it’s the dual lures of safety (“we will protect your innards from becoming zombie meal”) and upward mobility (ads for Fiddler’s Green play for the populace, despite vacancies being nonexistent). By using these to splinter the lower-class, the ruling class is allowed to reign unquestioned.

When we get our first glimpse of zombies, they’re introduced as former humans going through the motions of a quaint small-town American existence. There’s the cheerleader, her jock boyfriend, even a three-piece brass ensemble in a bandshell awkwardly fumbling with their instruments. The film’s “hero” zombie (known as “Big Daddy” in the credits) works as a gas attendant, coming out to pump for a car that isn’t there. But when the tranquility of their wholesome “1950s” existence is ruptured by a raiding party, they start to change in ways that are very un-zombie-like. Under the guidance of Big Daddy — the first “woke” zombie — they begin to communicate with one another, use weapons, even show emotion when other zombies are slaughtered. (This emotional progression was hinted at with the character of Bub in Day of the Dead.)

Romero’s use of zombies as stand-ins to criticize American culture was always blunt, whether it’s Night unveiling the accepted racism of Jim Crow-era America, or the ’80s consumerism predicted by Dawn. So, what the hell are we to make of the nearly functional zombies in Land? Are they the lower-class, the “waste humans” that have been around since America’s founding, exploited by the upper- and middle-class? Are they (we?) the Americans that are still too distracted by shiny things — one way raiding parties get past the hordes is by capturing their attention with fireworks — to notice the growing inequality? Are we one vocal and inspirational leader away from collectively seizing power for ourselves?

The collective action is, of course, what makes the slow-moving zombies of Romero more terrifying than the virally spread “runner” cousins in the post-28 Days Later era. The latter can be combatted with a scientific “cure,” the former are a movement that’s only getting bigger. One slow-mover isn’t scary, neither are two or three; it’s only bad when they mass enough to cut off escape routes, when however many bullets you have aren’t enough. And the end of Land is the same as all Romero zombie movies, that is, the zombies win and the humans (the “real” monsters, after all) are back on the run.

But this time, it ends with a team-up (of sorts) between the newly woke zombies and the shantytown outsiders. After Fiddler’s Green is destroyed, after the intestines of the elite are devoured, Big Daddy and Riley see each other in the distance, each leading their pack of survivors in different directions. One of Riley’s team members prepares to mow them down, but then Riley stops her. “They’re just looking for a place to go,” he says. In oura landscape of skyrocketing rents, migrant workers ducking past increasingly fortified man-made borders, and desperate refugees on the run from political wars, aren’t we all.