The Very Best Copy Of "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" And Just A Little Of Bill Burroughs...

The Very Best Copy Of “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” And Just A Little Of Bill Burroughs’ Methadone

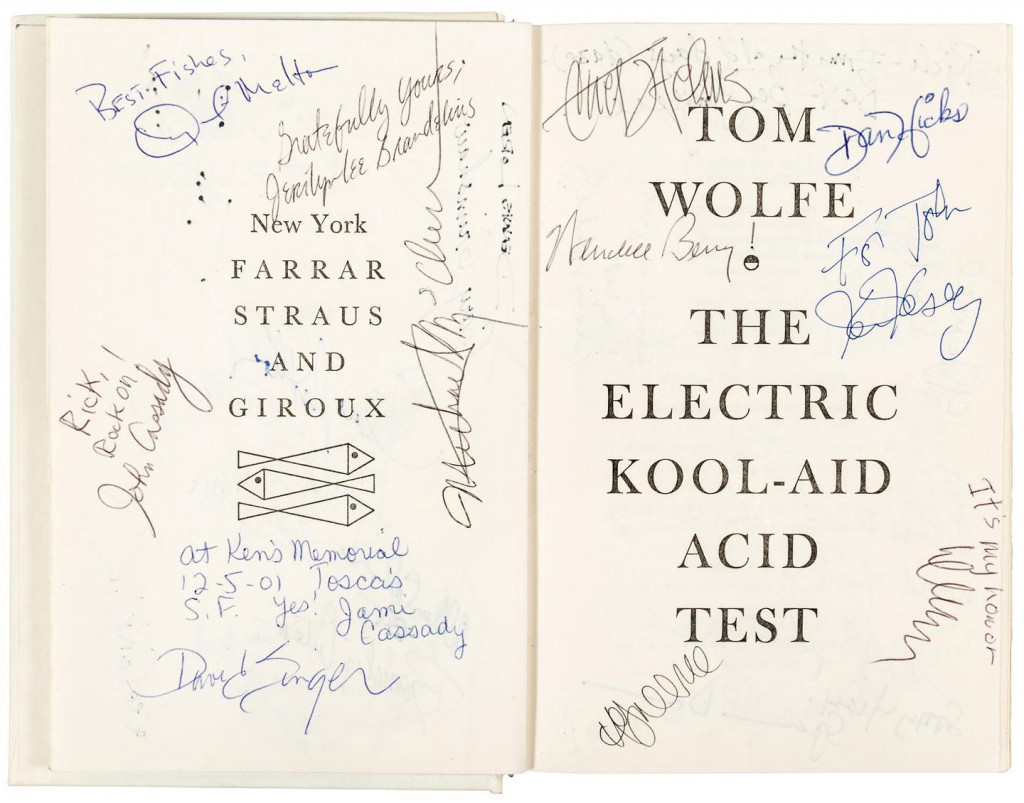

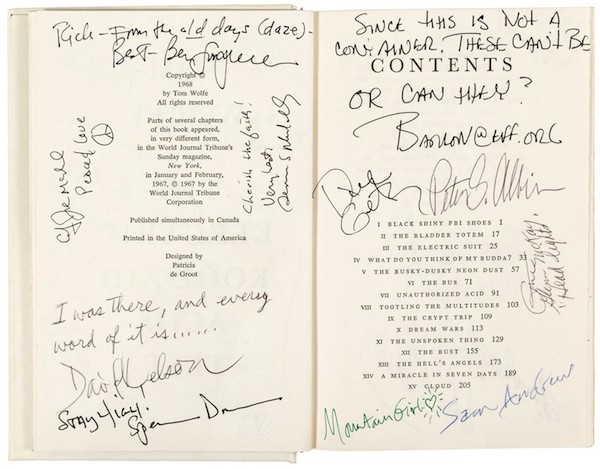

For 30 years, Rick Synchef carried around Tom Wolfe’s 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. It was a first edition purchased from a dealer, but it never occurred to Synchef that value might be lost with wear or anachronistic additions. He considered it to be a perfect novel, and collecting the signatures of Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters the ultimate homage.

“You have to understand, LSD was legal,” Synchef said. Lysergic acid diethylamide was the Prankster’s drug of choice, taken collectively at parties in hopes of achieving true intersubjectivity.

Synchef did not attend those parties, but longed to meet those who did. Every Sunday, after the newspaper arrived, he would study the calendar section and plan his week. If anyone connected to 1960s counterculture was appearing in Northern California, Synchef showed up with The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. The book was carried to countless readings, seminars, clubs, and about 140 Grateful Dead shows.

The frontispiece quickly became crowded with ink of varying thickness, with names scrawled in every direction. Jerry Garcia’s ex-wife Carolyn, who went by the moniker Mountain Girl, used a green pen, and added a heart with dashes running along the outer edge. There a peace sign, of course, and just one lone email address. Kesey turned to a less crowded leaf, joining other who had written in the margin of the title page. Jami Cassady, the middle child of Neal and Carolyn Cassady, signed the book at Kesey’s memorial at Tosca Café, a North Beach institution down the block from another, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Books.

Over time, the book became a kind of talisman. Every new addition seemed to take bit longer to procure. Instead of just flipping the book open, pen tip automatically and dispassionately applied to page, it was often put to rest. Signers would settle in with the book, running their fingers across the names of people who had once been so immediate and essential to their existence. How had they had fallen out of touch, they would ask Synchef, including him in the act of memory. Fan became confidante, the keeper of their secrets, the memories that didn’t make it onto the page.

For his part, Synchef declined to share them with me — with the exception of Allen Ginsberg, whom he vaguely described as displeased with Wolfe’s portrayal of him.

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is just one of many items Synchef is prepared to part with this week at PBA Galleries, an auction house in downtown San Francisco. The opening bid for Tom Wolfe’s signature-laden first edition will be $3,500; PBA estimates its worth to be $7–10,000. To accommodate his large collection, the sale has been divided into three parts. The second auction will be held in January 2014, which will feature yet more books, and the third auction, in May 2014, will consist of cartoon and poster art. Synchef began collecting as an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he estimates he “was tear-gassed or pepper-sprayed about 30 times.”

PBA Galleries has added a few dozen related items from other owners, including an empty bottle of methadone prescribed to William S. Burroughs, filled with rocks and dirt from his grave — along with a .45 caliber casing from the author’s own shotgun.

Although Synchef did collect handbills, posters and ephemera, items he recently discussed with Collectors Weekly, he reveled in the hunt for books, the process of exploring flea markets and record stores, used and antiquarian bookstores, and the thrill of searching through unorganized, unmarked boxes of decaying editions, often coming up empty handed.

“I’m single, and I don’t have anyone to pass it down to,” he said. “I spent most of my adult life living with this collection, always thinking about it and trying to make it better.”

Synchef did not consider contacting archives that collect Beat materials, although he hopes they’ll consider bidding on the auction. In truth, he hopes it goes to another collector, someone who will appreciate his efforts, having expelled their own on similar undertakings.

Before we hang up the phone, Synchef asks me not make him sound like an “old hippie,” but goes on to assure me that he is indeed an old hippie. He takes issue with dismissive nature of the term, and how it might reduce the importance of his collection, and what he sought to preserve all these years.

“The Acid Test was the start of the 1960s counterculture, but these people are like burnt-outs, they’re caricatures. That’s not the way to treat the first generation of a politically active youth culture in America.”

Alexis Coe is a columnist at The Awl, The Toast, and SF Weekly. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, and other publications. She holds an MA in history, and was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Hammer Time is her guide to all things wacky and fascinating in the auction world.