A Q&A With Editta Sherman, Celebrity Photographer, Age 100

by Sean Manning

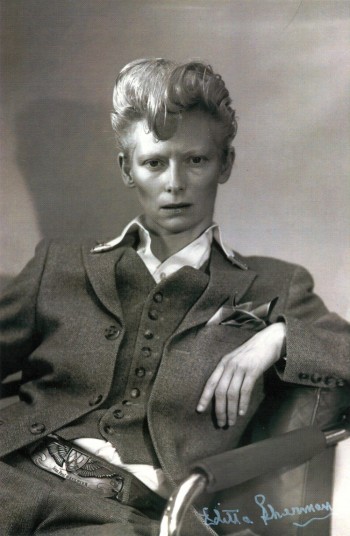

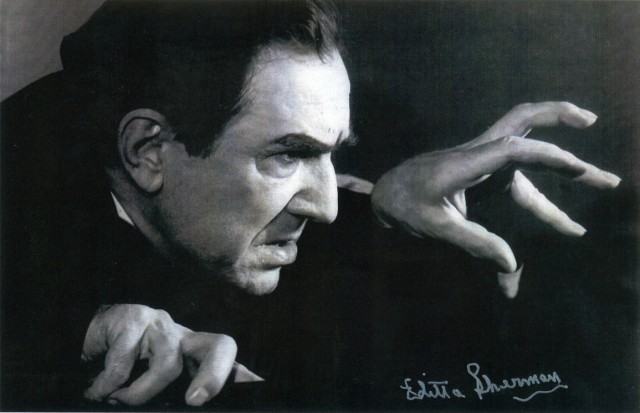

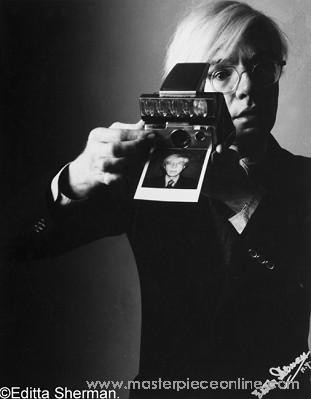

Looking at Editta Sherman’s celebrity portraits, you wonder: Who will be this era’s Tyrone Power? Which current movie star will be the one hardly anyone recalls seventy years from now? Bale? Brody? Bloom? Whose name will draw blank stares from the Class of 2082? If you saw the documentary Bill Cunningham New York, you certainly remember Sherman, the vivacious nonagenarian photographer who was Cunningham’s Carnegie Hall neighbor and the muse for his shamefully out-of-print book Facades. Since 1949, she lived and worked in the artist studios above Carnegie Hall. She also raised five children there. In 2010, she, Cunningham, and the other remaining tenants were moved out so the studios could be made into offices and classrooms. Sherman just celebrated her 100th birthday, and through July 29 the gallery CPW25, located nearby her new Central Park South apartment, is having a retrospective of her work — her first exhibition since 1967. While some of the subjects are instantly recognizable — Joe DiMaggio, young Charlton Heston and Angela Lansbury, and, from just a few years ago, Tilda Swinton — many others are Old Hollywood forgottens such as Power, Kim Hunter, and Frank Morgan. Sherman’s methods are equally outmoded: she uses an 8×10 camera, same as her photographer father from whom she learned the craft. Last week, I spoke to Sherman about nearly trysting with Power, selling old clothes to Swinton, and dancing ballet for Andy Warhol.

How did you get started in photography?

I was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1912. My father had a studio there. He had a studio in the back and a big window in the front of the building and we lived in the back. We weren’t there very long because we moved into New Jersey. So my father had another studio in New Jersey. When I got to be about ten years old or so, I used to help my father with his prints and washing them in the dark room. Small things, you know, just to give him a helping hand. By the time I got to be fifteen, my father had two or three studios. Because it was a time when photography was just coming up. My father would come from New Jersey to New York to go to the Kodak exhibits they used to have for people interested in photography, and I got to go with him. And then the small cameras came out, and it was my birthday, and he gave me a Brownie. I laughed at the Brownie because, you know, he had this great big camera. And I said I didn’t want this little camera. I don’t think I used it, actually.

What do you think of digital photography?

Well, I’m not used to it yet. But I guess that’s the way it’s gonna be. It’s a help with the chemicals. I mean, you don’t have to bother with chemicals. I’ve had my hands in a lot of chemicals. I’ve got this problem with my hands. Of course, you get better quality with the chemicals. You have to know how to wash them and so on. They last — they’re more lasting.

Do you have any favorite photographers?

I love Karsh. I met him when he was doing a show in Chicago. He was interested in my pictures. My husband sat there and talked to people. Karsh said, “You did these photos?” And he said, “No, my wife over there.” So he came there and saw the pictures and I know that he didn’t just throw them out like that. You know, he thought about it. I guess he thought, Well, someday she’s going to be quite famous. I think that’s what he thought. But he died.

How did you end up in Carnegie Hall?

My husband had gotten a job in California. We lived in Berkeley. This little cottage was just beautiful. It had an antique stone fireplace and a nice little nook to have dinner. The rent was only like $50. I had the one baby and another one coming. I loved California. It was the weather that I liked about it. I just couldn’t stand the snow and cold weather. I said to Harold, “I want to stay right here.” But then we moved to a farm in Washington, D.C. The war was still going on. We had fifty acres, cows, chickens, pigs. We were there for a couple of years. But things were very difficult. It was hard to get somebody to help and take care of the land. And we had to get into a place where I could be shooting. I was going to school and learning a little bit more. I was getting better all the time. Now I see a big ad in the paper — New York. It says, “Live and work in Carnegie Hall.” And I thought, Well, I don’t understand that. I mean, if they have music there, why would they want people living there? And my husband said, “Well, we’ll go and see them about it.” So he got up there, and there was this man that he saw. And he had a big studio, and he said that he was giving it up because he was going to California. He was a producer. The rent at the time was like a couple hundred dollars, and it had skylights, and it was right by the elevator, so that it was a very good thing for me, because now with five children —

Where did everybody sleep?

I had some mattresses. I put them on the floor at night. And then they would go to school, the older ones. And the others would have to be around. We had the automat on 57th Street. So the older one would go there — by that time he was about ten years old — and he would take care of the other children, take them over to the automat.

What’s your favorite of all your photos?

I don’t know. Every character has its own beauty. Tyrone Power was one that was memorable. He came to New York. He had been in the pictures in California. But they wanted him for a show here on Broadway. I said, “Oh, I would really love to photograph him.” Because I’d seen him in so many different pictures. I had already photographed Raymond Massey, who was also in the play. So I told my husband to go backstage to see Raymond Massey and he would introduce him to Tyrone Power. It was cold and snowing. My husband got backstage and Raymond Massey said, “Oh yes, I remember her. There was an elevator there and I didn’t know about it and walked up five flights of stairs.” How could he remember that? I was all excited waiting at home, wondering how this thing was gonna wind up. And sure enough Tyrone Power was very wonderful to say he’d be very glad to come and I could photograph him. So there was a very good opening for me with Tyrone Power, because not only did he come and I photographed him but he loved the pictures that I took of him and he did nothing but advertise them. He would have the pictures hanging in his dressing room. And when people came backstage to salute him, they would look at the picture. “Oh yes,” he’d say, “that wonderful picture was taken by Editta Sherman.” And so first thing you know, I would have a call: “Oh, I’ve seen those marvelous pictures you did of Tyrone Power…” And then they had something else that they wanted him to do on Broadway so he came back to New York. And when he knew that my husband died, he felt terrible. He tried to drum up more business for me. I had a little crush on him, like he had a little crush on me. But we never got together. That was before he met his wife. That second time he was in New York, he invited me to come up to see his apartment. But I thought it best not to. Then he died.

How did you meet Tilda Swinton?

Which one?

Tilda — Tilda Swinton. The modern actress.

Which one?

Tilda Swinton.

Oh, you mean the woman. Well, I had a man who did some publicity for me. And he’d get a lot of clients for me. And he had this Swinton. I didn’t know anything about her, actually. He said, “They’re gonna do a story on her. You’d be in the magazine. They’re not gonna pay you any money but you’d get the publicity. I’m gonna bring her over and you can take her photograph.” “All right,” I said. So she comes over with her agent. I had some of my clothes hanging. I had this antique dress hanging. And her agent said, “Do you mind if she tries that dress on?” I said, “No, not at all.” So she puts the dress on. And she says, “Would you sell it?” “Well,” I said, “I wasn’t thinking of selling it. But if you want to buy it, it’s okay with me.” She said, “Well, what would you charge?” I said, “I don’t know. $500?” “Well,” she said, “that’d be fine. I’ll take it.” So she gave me $500. It was an old dress. It was very nice. I really liked it. Didn’t fit me.

And Warhol?

Oh, Warhol. I had at the time some railings from the Paramount Theater. A friend of mine was an antique dealer and she bought them and she had no place to put them. So she put them in my place. There were six of them, and they were solid bronze. Evidently, Andy knew about them, and he wanted to buy them. So one night from the Russian Tea Room a friend of his, what’s his name, Paul Morrissey, he calls up and says, “Me and Andy are here having dinner and Andy wants to meet you. Is it too late to come up?” It’s ten o’clock, and I say, “No, I go to bed late. Come up.” So they both came up and they sat there. I had a little bench where people could sit. He was very frightened-like. He would talk to Morrissey, and then Morrissey would tell me — Andy says this and Andy says that. “Andy says that he would very much like to do a film on you.” “Oh,” I said. “Well, that’s very nice.” He says, “He doesn’t have much money to pay you, maybe fifty dollars.” So they made another appointment and I got all ready and they came up. I said, “Without a script, what am I supposed to say?” “Well, Andy says say anything that comes to your mind.” “Anything that comes to my mind?” I said. “I don’t know. My mother used to recite little Italian poetry. We’ll take the railings and make a circle and I’ll be in the circle.” And he said, “That would be just fine. Get in the middle of it and you will be the mother of a son that’s been murdered.” So I said, “Okay.” I did my little recitation, and I talked about my son being murdered, I didn’t know anything about it — things like that. Then I said, “You know, this is not very good. Maybe we change it. How about me trying to do The Dying Swan? The dance.” And he said, “Oh, that would be fine.” So I went into my other studio, which I had one across the hall, to put my ballet costume on. In the meantime, this lady comes in who’s a friend of his, and she comes over to Andy and says, “Andy, I want to know where my shampoo is.” And I thought that was a crazy thing to ask. Shampoo? Why’d you ask for shampoo? You can get that in a drugstore. He said, “Look, will you please stop playing around. I don’t want to waste Mrs. Sherman’s time. Now get out there and start it again.” So she goes out and knocks on the door, and I say, “Come in.” And she comes in and I see she had taken all her clothes off, and everything was on the floor. And then she was in my little desk, and there were some pearls there, and she held the pearls up saying, “Bella, bella.” God, I saw that, and said, “When my children see this, they’ll think I’m crazy.” And that’s the way it ended. I said, “Well, I think you got enough film now, Andy.” And then he died, of course.

Related: Portraits From A Cross-Country Road Trip

Sean Manning is the author of the memoir The Things That Need Doing and editor of several nonfiction anthologies, most recently Bound to Last: 30 Writers on Their Most Cherished Book. He also edits the blog Talking Covers. Editta Sherman’s photos used with her permission.