The Jack the Ripper Content Economy

The murders that will never be solved by selling a lot of books

This fall marks the 128th anniversary of a series of murders in London’s Whitechapel district — at least five, for sure — that have long transformed from an investigation to a vague romantic aura that haunts the more macabre corners of pop culture. The case is more frostbitten than cold: due to a combination of muddled evidence and the deteriorating effects of time, the case will never be solved. Yet despite the lack of leads — in fact, because of them — the content business of Jack the Ripper is still booming.

An Amazon search spits back nearly 4,500 items, IMDb returns 119 TV episodes or movies, but even those numbers don’t account for the subtly titled video games, websites, stage plays, operas, paintings, radio dramas, songs, costumes, or various Etsy crafts that seek to capture that “Jack the Ripper aesthetic.” You know it: that sinister silhouette with top hat and cane, sounds of raindrops and horse hooves echoing on candlelit cobblestones, frantic police whistles in the dark followed by cries that they found another. Jack the Ripper is a perpetual content machine from beyond the grave.

As all brands do, it started with a name. Before he was officially christened, newspapers referred to the killer as either the “Whitechapel Murderer” or “Leather Apron,” taken from a clothing item worn by a suspicious person police wanted for questioning. But on October 1st, 1888, London’s Metropolitan Police released a letter that had been previously received by the city’s Central News Agency. It was signed:

Yours truly,

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

Why this single letter — of the dozens claiming to be from the killer — was given legitimacy is unclear. It was received on September 27th, three days before the infamous “double event” — the Ripper’s first two victims were found on August 31st (Mary Ann Nichols) and September 8th (Annie Chapman) and then two (Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes) were found on September 30th; the fifth known victim, Mary Jane Kelly, was found later, on November 9th — and it referenced cutting “the ladys ears off”; Eddowes was found with her right earlobe severed. That similarity was good enough for the cops, even though it was subsequently proven a hoax when another letter surfaced with different handwriting and spelling, but further legitimized because it also came with a human kidney, allegedly from the body of Eddowes. No matter; the brand had been established. The media frenzy now had a name to latch onto.

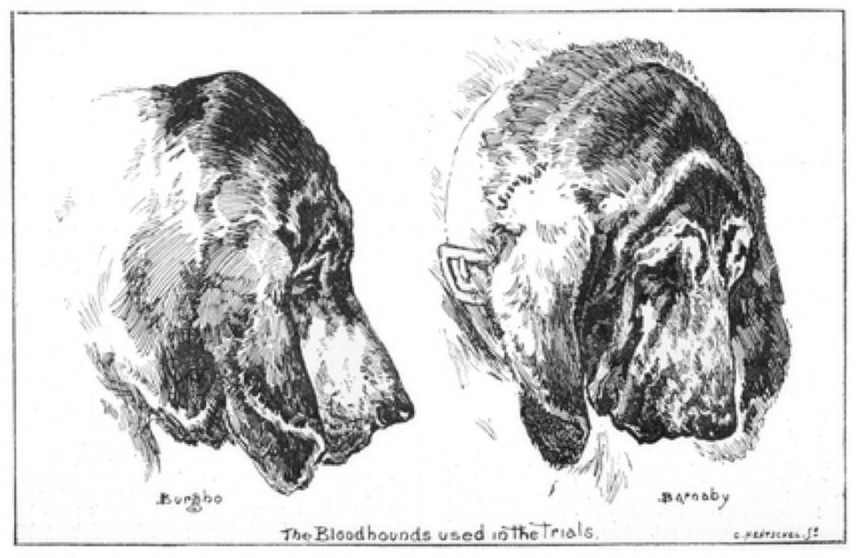

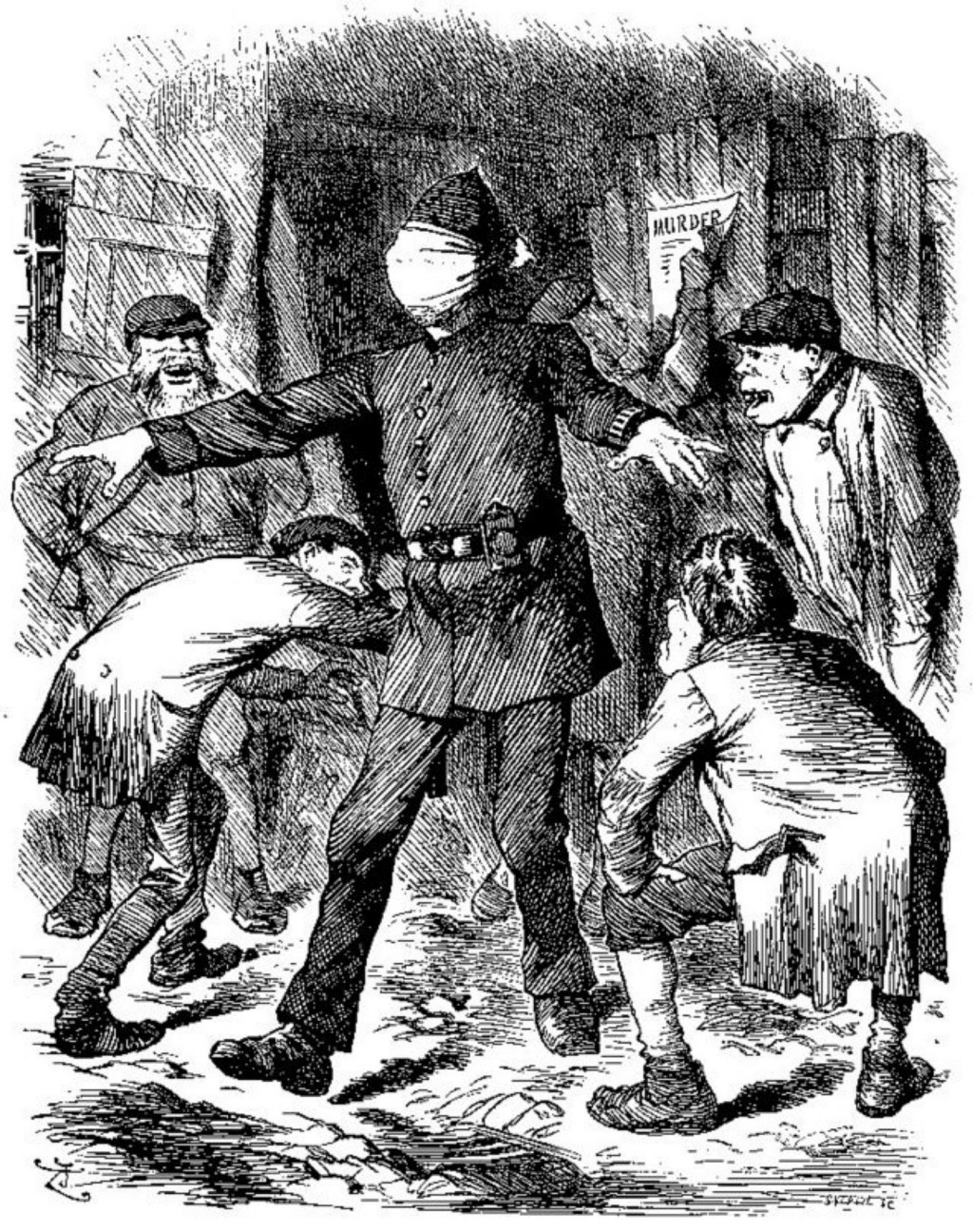

Newspapers like The Penny Illustrated Paper and Punch sold like whatever the nineteenth-century British equivalent of a hotcake was. They’d have the latest details: maps of murder sites, sketches of suspects and victims (some gory, some angelic), inquest transcripts, even the blow-by-blow of the heavily mocked sniff-hunt through London’s parks by the police commissioner’s two bloodhounds, Burgho and Barnaby. It was a worldwide media sensation, with readers as far flung as Mexico and Jamaica clamoring for coverage. But as the murders dried up over the next few months (at least those gruesome enough and without obvious suspects), the column inches of 1889 were commandeered by other worries of the day. Even the coverage of the Ripper case itself shifted, from being a story about a string of gory murders, to focusing on the plight of those living in the squalid conditions of London’s East End; there’s a pretty direct line from Ripper coverage to the stirring of socialist sentiment and ultimate creation of Britain’s Independent Labour Party in 1893.

The Ripper News Mill sputtered to life again in March 1903, when former London Metropolitan Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline told the Pall Mall Gazette that his favorite suspect (George Chapman, birth name Severin Klosowski) had been convicted of murdering three women with poison and set to hang. But even interest in that thread soon dissolved among the other claims, leaving newspapers with only scraps of rumors, anniversaries, old man memoirs, retirement notices, and, finally, short mentions in the obituaries of ancillary players.

Any era’s aesthetic becomes commodity as the past drifts backwards in time, but the massive changes to everyday life in the early twentieth century — say, the widespread use of electricity that merged day and night into a single waking nightmare — provided folks with plenty of reason to be nostalgic for the Victorian era. Into this seedbed blossomed renewed interest in the serialized Sherlock Holmes, gothic books like The Curious Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and stories about this vague evil character named Jack the Ripper, no longer a real-life serial killer still on the loose, now only a murky shadowy spook that authors could use to spice up their stories. While actual news evaporated, the Ripper brand flourished like a franchise. Fictionalized accounts had been published from the get-go — the earliest being John Francis Brewer’s The Curse Upon Mitre Square, published in October of 1888, while the murders were still taking place.

In 1907, German publishing house Verlagshaus für Volksliteratur und Kunst published the thirty-two-page dime-store novel How Jack the Ripper was Taken, the first to take the logical step of pitting Sherlock Holmes against Jack the Ripper. In 1913, Marie Belloc Lowndes published The Lodger, in which a London couple suspect that the mysterious stranger staying in their upstairs room is actually the murderer. (A 1927 film adaptation of the novel was Alfred Hitchcock’s first hit.) Leonard Matters blurred the lines in 1926 with The Mystery of Jack the Ripper, the first non-fiction “serious examination” that recounted a deathbed confession from Dr. Stanley, a pseudonymous doctor who claimed he’d committed the crimes as revenge for his son, who’d died of syphilis contracted by a sex worker. It was obvious bullshit, more Blair Witch-style salesmanship than anything else, but it was the first in the Ripper whack solution sub-genre, trotting out unverified claims as indisputable solutions. In 1943, Robert Bloch, the horror/sci-fi master who’d yet to write his novel Psycho, turned the murderer into an immortal who killed to remain so in his short story “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.”

Soon the Ripper achieved full cliché status, appearing in stage plays and operas, radio dramatizations and film, always donning the romanticized gear of top hat, black cape, and walking cane (a polished look that the real killer, likely a resident of the poorest neighborhood in London, most certainly didn’t have). But it was these depictions that, oddly, fueled the next phase of Ripper Content, which simultaneously pushed back against fictionalized hype while doubling down on the false aristocratic aesthetic.

In 1970, a surgeon named Thomas E.A. Stowell wrote an article titled “Jack the Ripper — A Solution?” for the quarterly crime magazine The Criminologist. Ultimately, this short piece had two important things going for it: it attracted tabloid sensationalism by claiming a “Royal conspiracy,” wherein the Ripper was actually Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor; and Stowell died within a month of the piece being published, in the middle of a media blitz. The BBC ran a popular six-episode miniseries in 1973 that retold the Jack the Ripper case through a weird (innovative?) combination of present-day fictional investigators and dramatized recreations; the final episode dipped its toe into Stowell’s royal conspiracy theory. Journalist Stephen Knight saw the show and decided to poke his nose around some more.

In 1976, the twenty-five-year-old Knight came out with Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, a 284-page investigation that unveiled the grand conspiracy between royal family, the Freemasons, and painter Walter Sickert, all to keep Prince Albert safe from prosecution for his grisly deeds. Despite Knight’s main source later claiming that his testimony was all a hoax, as well as the glaring logic holes if one merely glanced at the evidence presented at face value, Knight’s tale was just the right mix of murder, bluster, celebrity, and sensationalism. It was predictably a smashing success. The book necessitated twenty editions and thrust Knight into the media spotlight: The Ripperologist was born.

At this point, there was a schism in Ripper Content. There was the continuation of Ripper Entertainment as generic gothic madman — a dark silhouette to be trotted out during the Halloween season or as a walking horror movie trope. But there was also the rise of “serious examinations” into the case, as a kind of counterstrike against the popular acceptance of the bullshit claims from Knight, who died in 1985 from a brain tumor. The Complete Jack the Ripper, Donald Rumbelow’s account of the case first published in 1975, was now continuously revised and republished. Philip Sugden compiled more case facts for The Complete History of Jack the Ripper in 1994, the same year Paul Begg’s Ripperologist magazine began printing sixty-two pages of brand-spanking-new Ripper Content every other month. Stewart Evans and Keith Skinner combed through the Metropolitan Police archives and published weighty volumes of source materials, from a compilation of every letter the police received claiming to be from the murderer, to a 750-page illustrated encyclopedia of the case’s written records. (On the entertainment side of things, writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell developed the graphic novel From Hell, between 1989 and 1996, based in part on Stephen Knight’s royal conspiracy; Johnny Depp was later in an awful Hughes Brothers movie that was loosely based on it.)

Ripper Content finally went online in 1996, when Stephen Ryder created Casebook.org as a clearinghouse for it all. There are crime scene details, witness testimony, victim and suspect dossiers, reviews of every fiction or nonfiction book that’s ever been printed, a searchable index of Ripperologist magazines, and even a still-active message board, where users from around the world congregate to lob solutions and debate over non-canonical victims, 24/7. This being Web two-point-whatever, there’s also a section for podcasts.

The rise of legally admissible DNA evidence was obvious fuel for the next generation of Ripper Content. In 2002, bestselling crime novelist Patricia Cornwell’s Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper — Case Closed offered irrefutable DNA proof that painter Walter Sickert could not be ruled out as a suspect in the writing of a few Ripper letters. Read that sentence again to find the holes in her claim. Despite it being obvious pseudoscience standing on the shoulders of baseless accusations, with a name attached like Cornwell’s — who, as every press release noted, sold over 100 million copies of her Scarpetta novels — the popular media latched on. Book-release hype masked as real news culminated in an hour-long TV special on A&E that features easily my personal favorite moment of Ripper Content: This hilariously awkward heist-movie montage of Cornwell walking to the Public Records Office with her “team of experts,” all set to a kickass Radiohead bassline.

The Ripper Content’s whack solution sub-niche never really went away, Cornwell just gave it new life through financial relevance. Each book-length whack solution release takes the same general journey. They’re first-person accounts that begin with the author becoming obsessed with the case, which allows for a re-telling of the same basic facts everyone knows by now. But then (then!), the author stumbles upon some contradiction, or missing link, or a clue that nags at them and forces them to examine further. That leads them right to the doorstep of their suspect. Except all the suspects are dead. The rest of the book becomes a sleight-of-hand act, trying to link their suspect to the murders without overt shoehorning, a deft backwards compatibility that’s easy to spot once you know how to look for it.

The latest popular attempt of finding a solution is They All Love Jack, a sprawling (read: rambling) 864-pager released late last year by filmmaker Bruce Robinson, best known for Withnail and I. Robinson names Michael Maybrick, traveling musician brother of previous suspect James Maybrick, as the Ripper with a heaping helping of proof that is, let’s say, not so great? But the most interesting part of the book comes early, in a chapter called “A Conspiracy of Bafflement,” where Robinson scorches the trail cleared by the Ripper researchers who went before. He calls Knight’s book “a well-presented dissertation of comprehensive nonsense” and “a twerp history. (Awesomely phrased owns, but par for the course in terms of criticism; Knight is low-hanging fruit by now.) Robinson goes on to criticize the entire landscape of “serious examination” Ripper Content created since, mocking the Ripperologists as ineptly gullible, casting the lot of them as doofus blokes in a false flag operation. It’s fun.

While Robinson’s book garnered what may seem like a shift in the tone, it’s really just a blend of the two types of Ripper Content that exist: “serious examination” and entertainment. In fact, any new serious examination of the case can’t really be all far apart anymore from the other Ripper entertainment out there, the video games, or BBC’s Ripper Street, or the baseball team that tried to call itself The Rippers. Or the forty or so Ripper Walk tours throughout London that take tourists over the same cobblestones and into the same bars where the murderer and his victims stalked so long ago; one tour tries to set itself apart with a projection set up that it brands “Ripper Vision.” It’s macabre, but it’s okay. It’s fun!

Last year, the Jack the Ripper Museum opened in London. It has five floors of recreations — See Mary Kelly’s bedroom! See an old-timey mortuary! — and it bills itself as a “serious examination” of the crimes. This, despite the museum hiring actors to traipse around in that erroneous top hat and cape look. It all fits the macabre tradition of horror attractions like The London Dungeon, which, fair enough, but the museum really, utterly biffed its opening. While under construction, the museum’s director sold the prospect of the new installation to the public as “the first women’s museum in London,” with photos of suffragettes and Asian women protesting racist murders in the 1970s included in the planning application. But when the boards were removed for the museum’s opening, its goal had evidently changed to focus on Jack the Ripper. Last Halloween, they even offered “selfies” near victims’ corpses. In the face of mounting criticism, their PR flack claimed the murders — of women, of prostitutes, with genitals slashed — were not technically “sexual violence.” It was not a great look. Boisterous protests accompanied a petition to close down the museum. A year later, the unrest has died down and it’s still open. With nearly 300 reviews on TripAdvisor, the museum has a four-star rating; the word “fun” pops up in at least thirteen. But was this outcry finally evidence we’re getting tired of Ripper Content?

After all, it is a case that will never be solved. Any suspects are long dead, along with their children, and their children’s children; punishment and closure are no longer possible. Even the basic facts of the case are up for dispute. Not only do people have difficulty agreeing on exactly how many victims there were, there’s a question of whether or not there was a lone killer at all and the police weren’t just confused. The best theory to that end was first put forth in 1910 by Scotland Yard officer Sir Robert Anderson, and supposes a set of unrelated female murders and a journalist trying to bring publicity to the impoverished region, not unlike McNulty’s gambit in season five of The Wire.

Besides, no matter the proof attached to it — confession, DNA, some weirdo walking out of a time machine saying in a Cockney accent, “I did it, and this is how” — any “solution” will be widely and enthusiastically disputed as fake. Too many businesses have stock in the idea of Jack the Ripper as vague murderous wraith to allow a true solution to destroy their moneymaker. The Ripper Content beast needs to be fed, debunking keeps us hungry. More than a century after the murders, there’s no place left for “serious examinations” to pin down the killer. Any billing for legitimacy is really just a veiled excuse to dwell in the world’s most popularly-accepted snuff material. The killer got away. All that’s left is the gross entertainment.

Rick Paulas likes Halloween. He previously examined America’s ghost tour industry and the online market for haunted items.