The Vexed Posthumous Life of Oscar Wilde

The Vexed Posthumous Life of Oscar Wilde

In 1914 Max Beerbohm wrote to Vyvyan Holland, the younger son of Oscar and Constance Wilde, on the occasion of Holland’s wedding. Beerbohm sent his regrets for not having been able to attend the wedding, together with a present.

It has the advantage of being easily breakable if you don’t like it. The glasses are (you will be relieved to hear) of British manufacture, but I can’t tell you just when they were made. I asked the old man in the shop to tell me the date of them. Whereat he stroked his chin and, looking at me over his spectacles, said “Well, Sir, what would you say to William IV?

Beerbohm, the author of the celestial Zuleika Dobson, was then 42, and Holland 27.

Beerbohm had first met Wilde while still at school at Charterhouse; his older brother, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, produced one of Wilde’s plays. “Beerbohm was quick and clever: Wilde taught him to be languid and preposterous,” writes Richard Ellmann, Wilde’s biographer.

There are a few other letters between Beerbohm and Holland in the Ransom Center’s collection in Austin, all written in the warm but slightly formal tone still in use between grown children and their parents’ friends. Beerbohm’s letters are particularly beautiful to look at and handle — in addition to writing, he was a well-known caricaturist, with a precise, delicate line — he wrote in a round pleasant hand, on the fine paper people once used for letter-writing.

Nearly forty years later, in a different world entirely, on September 14th, 1953, Beerbohm wrote to Holland again (this time from the Villino Chiaro, his house in Rapallo) expressing his regrets once more. “I wish very much I could have the honour of unveiling the plaque, but I am too old to travel.” So begins the tangled story of the Tite Street memorial.

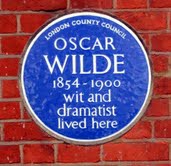

This is the plaque Beerbohm meant, which may still be seen at 34, Tite Street (formerly no. 16.) It’s a terrifically famous street in Chelsea, long one of London’s most fashionable neighborhoods. John Singer Sargent lived in this street, and Augustus John, and Whistler. Nowadays these houses are worth upwards of £15 million. Sterling! They must be some of the most expensive dwellings (per square foot) on earth.

The London blue plaque scheme began in 1866. There are over 850 plaques extant, of nearly a thousand total (the rest were on buildings since lost or demolished.) The first one commemorated Lord Byron’s birthplace in Holles Street. In order to be eligible to have a blue plaque put on the building in which you strove, suffered, were born or died, you must either have been dead for twenty years, or have passed the centenary of your birth, “whichever is earlier.”

Then there is a long process, involving the submission of a complicated proposal to the Blue Plaques Team, then another hurdle in the panel review, a final detailed review by a historian, and finally, if you make the cut, consents are sought and granted by the building owner. Nine or so new plaques go up each year.

So this whole procedure had been set in motion for Oscar Wilde’s famous house in Tite Street, in honor of the centenary of Wilde’s birth (1854), and Vyvyan Holland had written to Beerbohm in Italy in 1953 asking him to preside over the traditional plaque-unveiling ceremony, to take place the following year. Since Beerbohm couldn’t travel, in his response to Holland he suggested an alternate.

“As to who it should be I have no very clear idea. I am perhaps the only living writer who knew Oscar personally (and being so, I could, if you wished, send some sort of message to be read by the unveiler in the course of his address.) Part of Oscar’s claim on posterity, and the part which is perhaps most familiar to the present generation, is his dramatic work. So I imagine that John Gielgud, who is generally regarded as the leading actor of to-day, might be a good selection?”

Not only had Gielgud just been knighted, he had just had a spectacular success in a revival of The Importance of Being Earnest. Great idea!

But about two seconds later, on October 28, 1953, a missive of a much different character flew forth to Vyvyan Holland from the Villino Chiaro.

My dear Vyvyan

I was much distressed at reading the cutting that you have sent me about John Gielgud. What a very tragic thing to have happened!

You are of course absolutely right in feeling that in the circumstances the unveiling of the plaque could not be done by him. I should think you have very likely had a letter from him of his own accord to this effect?

What the hell was that about? Well, you are not going to believe.

***

First let us return to the history of the Wilde/Lloyd/Holland family.

Vyvyan Holland (b. 1886) had been taught, and/or forced, to deny any connection with his disgraced father for all his life. He was just nine years old at the time of Wilde’s first trial. But before that, both he and his older brother Cyril had adored their father, who was unending fun when he was around, which was less and less and less as time went on. His father, once so beloved and celebrated, and then in jail, banished, exiled, the betrayer of his beloved mother, the details of his secret life splashed all over the papers. Though Vyvyan Holland didn’t even find out what the actual trouble had been until he was sixteen.

All the same, before she died in 1898 (from a botched spinal operation after a fall down the stairs at Tite Street), Constance Wilde wrote to her younger son: “Try not to feel harshly about your father; remember that he is your father and that he loves you. All his troubles arose from the hatred of a son for his father [meaning the vile Lord Alfred Douglas], and whatever he has done he has suffered bitterly for.”

She died a matter of days later, aged just 39.

After her death, though, the Holland family went to court to ensure that Wilde wouldn’t be allowed to see his sons. Vyvyan was just fourteen when his father died, broke and washed up in Paris. His brother Cyril, by all accounts a super brilliant young man, was killed by a German sniper in 1915. Vyvyan Holland’s first wife Violet died young, too, in 1918, of injuries sustained in a fire. But he wound up having a long and reasonably happy life all the same. He made a fortunate second marriage, later in life, made peace with his past and wrote a celebrated book, Son of Oscar Wilde (1954). He was this really, really kind, good man.

Vyvyan Holland was denied admission to Oxford because of his father’s scandals. But Holland’s grandson Lucian (b. 1979) would be given his great-grandfather’s rooms at Magdalen College, Oxford (a name confoundedly pronounced “maudlin”), where he studied classics, as his great-grandfather had. Lucian’s father, Vyvyan’s son Merlin, lives in Burgundy; he too is a cool-seeming guy who has written several well-received books on the subject of his grandfather, and he has a lot of surprising and interesting things to say about his crazy ancestry.

Lucian Holland’s Twitter handle is @hollandlef. He’s into software engineering, somehow or other, and he blogs intermittently. He doesn’t go on Twitter a lot but is likeable and smart, to judge by what little we see there. He’s a little grumpy about the politics! Like who isn’t, eh what. Lucian Holland is also fantastically handsome. One of his few public remarks is worth noting, made at the public unveiling of the hair-raisingly awful statue of Oscar Wilde in central London: “Going to Ireland and seeing the beautiful houses that once belonged to the family, it struck me that if Oscar hadn’t blown it all, they might still be ours.”

So that is the deal with the Wilde men and their fascinatingly vexed history with their famous progenitor.

***

The details of the blue plaque application in Wilde’s case were largely overseen by a colorful character named Eric Barton. He was a Wilde specialist and bookseller from Richmond who was famous for refusing to let people into his shop at all. It was called Baldur Books, and specialized in ephemera. He and his wife Irina were instrumental in getting the Tite Street plaque approved in time to honor the centenary of Wilde’s birth. Their patience and persistence is a testament to the literary sensitivity and generally high quality in every respect of the Bartons — especially in light of the circumstances in which they undertook this project, as we shall see. They did most of the legwork, asking for advice every step of the way; on the recommendations of Beerbohm and Holland, they corresponded with Sir John Gielgud.

At the time all these letters were whizzing around London and Rapallo in 1953, things had been going terrifically well for the great actor. As we were saying, he’d only just been knighted. It was the Coronation year! He was lionized all over the place for being the best interpreter of Shakespeare in forever. He had a nice though I guess kind of jealous new boyfriend, an interior designer named Paul Anstee.

On October 1st, Gielgud responded to the Bartons: Love to! — or, to be more exact, “I would be very glad to unveil the plaque.”

Three weeks later, on the night of October 21st, Sir John Gielgud went to a cocktail party.

Now, it so happened that the English were on a crazy anti-gay tear owing to the Cambridge Five spy scandal; the super-hated communist spies Burgess and Maclean, both gay, had defected to the Soviet Union in 1951. So the English press and public were all oh, the gay and the radical communist anti-English blah blah! They even had some dumb politicians, notably Home Secretary Sir David Maxwell Fyfe (later 1st Earl of Kilmuir), vowing to Legislate The Gay Away in England. “Homosexuals… are exhibitionists and proselytisers and a danger to others,” he yelled in the Commons. No seriously, have a look at this clown.

So in 1938, 956 people [PDF] were arrested for being gay, and in 1952, there were 3,757.

How did even they figure out you were gay, in order to arrest you? Simplicity itself. Since it was still illegal to be gay even in private, they started entrapping people by stationing a gang of good-looking young policemen in the popular cruising spots. What a way to make a living! They were known waggishly (and horribly) as the “Pretty Police.”

So they would trick and then arrest these guys and keep them in the jug overnight, and then the judge would fine them ten pounds and tell them to go see the doctor about their gayness right away (not kidding — see the doctor! — so Monty Python, but it is true. Except in Monty Python, it would have been Graham Chapman angrily insisting that some buxom, simpering blonde go see the doctor about her persistent attraction to men).

So anyways, after this cocktail party, Sir John Gielgud put on his “cruising cap” (a literal hat he apparently wore sometimes while cruising, I guess for increased anonymity) and went along to the equivalent of the bathhouse, namely, the public lavatory in Fulham, in search of companionship. Sounds a little seedy maybe, but these public lavatories were actually really lovely little buildings, and cruising in the UK was and is called “cottaging.”

There Sir John was entrapped and collared by a member of the Pretty Police.

The matter would have passed without much incident, except that there was a reporter from the Evening Standard on hand at the court the next morning, just randomly, and he happened to recognize the actor’s surpassingly beautiful voice. So that very afternoon the Standard’s front page bore the headline:

SIR JOHN GIELGUD FINED

“SEE YOUR DOCTOR THE MOMENT YOU LEAVE HERE”

And that is why, even though he’d accepted the task of unveiling Oscar Wilde’s blue plaque on Tite Street just weeks before, Gielgud had to withdraw from the gig. He was so very loved by the public that the scandal didn’t hurt him much, fortunately, in his profession. But he was a shy, private man, and super hurt by the scandal personally.

In the event, Sir Compton Mackenzie presided over the unveiling of the Tite Street plaque, and he did indeed read a note sent from Italy by Max Beerbohm, which read in part:

I suppose there are now few survivors among the people who had the delight of hearing Oscar Wilde talk. Of these I am one.

I have had the privilege of listening also to many other masters of table-talk — Meredith and Swinburne, Edmund Gosse and Henry James, Augustine Birrell and Arthur Balfour, Gilbert Chesterton and Desmond MacCarthy and Hilaire Belloc — all of them splendid in their own way. But assuredly Oscar in his way was the greatest of them all — the most spontaneous and yet the most polished, the most soothing and yet the most surprising.

That his talk was mostly monologue was not his own fault. His manners were very good; he was careful to give his guests or his fellow-guests many a conversational opening; but seldom did anyone respond with more than a very few words. Nobody was willing to interrupt the music of so magnificent a virtuoso. To have heard him consoles me for not having heard Dr Johnson or Edmund Burke, Lord Brougham or Sydney Smith.

That voice is gone forever, alas. The sole alleged audio recording of Wilde, reading his poem “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”, was deemed a fake by researchers at the British Library in 2000. But I broke one of my own rules today, because I couldn’t find one anywhere else, and bought something on Amazon. It’s an out-of-print CD compiled from the British Library’s collection of audio recordings of writers born in the 19th century, including the voices of Agatha Christie, James Joyce and Max Beerbohm. Note: there are a few left!

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.