What To Read This Weekend

The only post-election piece you should really bother with.

There’s a monster of a piece in next week’s New Yorker that will serve as a temporary salve for your aching brain, for at least as many minutes as it takes you to read it. David Remnick offers a glimpse of last week’s events through the eyes of the guy getting evicted from the White House at the end of January. President Obama is as maddeningly calm and and sly as ever, winkingly telling Remnick he’d say how he really felt about the election result at some future date—off the record, over beers.

In some ways, it is Obama’s job to give this big interview, to calm the worried liberals, to reassure Democrats that what they have to do next is not only achievable but necessary. Of his strategic equanimity in receiving Trump for a visit at the White House, Remnick writes:

Obama was also trying to engage the world in a willing suspension of disbelief, attempting to calm markets and minds, to reassure foreign leaders and, perhaps most of all, millions of Americans that Trump’s election did not necessarily spell the end of democracy, or the rise of an era of chaos and racial enmity, or the suspension of the Constitution. This is not the apocalypse.

Obama’s insistence that this is going to be okay because this is what we do and this is the process is only so helpful, and I’m sure there are a lot of people who wish he were more angry on their behalf. But he insists this is how he really feels, and that he does not need a Key & Peele “anger translator.” “Look, by dint of biography, by dint of experience, the basic optimism that I articulate and present publicly as President is real,” he tells Remnick.

“It’s what I teach my daughters. It is how I interact with my friends and with strangers. I genuinely do not assume the worst, because I’ve seen the best so often. So it is a mistake that I think people have sometimes made to think that I’m just constantly biting my tongue and there’s this sort of roiling anger underneath the calm Hawaiian exterior. I’m not that good of an actor. I was born to a white mother, raised by a white mom and grandparents who loved me deeply. I’ve had extraordinarily close relationships with friends that have lasted decades. I was elected twice by the majority of the American people. Every day, I interact with people of good will everywhere.”

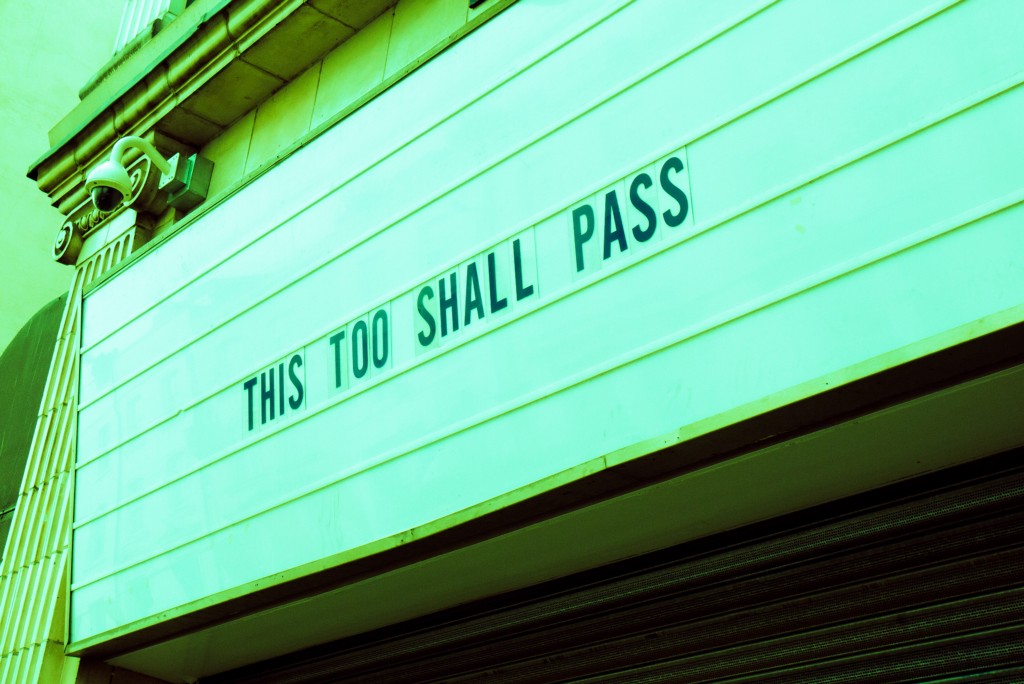

Isn’t Michelle just the luckiest? There’s a feeling throughout this interview that Obama is being the wise dad at the end of the family sitcom. So this week’s planned activity didn’t pan out the way you thought it would? Let’s sit down on the edge of the bed and let me put this into perspective for you. The ultimate this too shall pass. There’s also the feeling that we’re going to remember Obama as one of the best dads we’ve ever had, at least in a sociological sense:

Obama is a patriot and an optimist of a particular kind. He hoped to be the liberal Reagan, a progressive of consequence, but there are crucial differences. For one thing, Obama does not believe in the simplistic form of American exceptionalism which insists that Americans are more talented and virtuous than everyone else, that they are blessed by a patriotic God with a special mission. America is a country that was established on the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers and improved upon not merely by legislation but also by social movements: this, to Obama, is the real nature of its exceptionalism. Last year, at the fiftieth anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery march, he stood on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in Selma, and defined American exceptionalism as embodied by its heroes, its freedom fighters: Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, John Lewis, the “gay Americans whose blood ran in the streets of San Francisco and New York”; its Tuskegee Airmen and Navajo code-talkers, its 9/11 volunteers and G.I.s, and its immigrants — Holocaust survivors, Lost Boys of Sudan, and the “hopeful strivers who cross the Rio Grande.”

It is heartbreaking to think that Donald Trump won by, among other things, stoking a pervasive fear of these hopeful strivers who made America so great in the first place.

Of the ninety-minute meeting with Trump in the Oval Office, Remnick writes, “Obama had steeled himself for the meeting, determined to act with high courtesy and without condescension.” One wonders whether the president-elect will be capable of same when his turn comes to gracefully pack up and salute the next poor soul into the hot seat.

Finishing the piece may not convince you fully that just because this isn’t the end of the world doesn’t mean it’s not pretty miserable to live through. But it will have the effect of a warm, caring hand rubbing circles on your back, maybe brushing your hair aside as you spit up the last of the bile. It’s not over, you won’t ever really get used to the nausea, but at least now you know how to live with it.

You can read the rest here: