Our Culture Needs Better Monsters! An Interview with Brian McGreevy

by Desiree Browne

In an essay for New York’s Vulture blog last year, author Brian McGreevy argued that “over the last decade, something has gone terribly wrong with the modern vampire. Take the biggest offender, Twilight. Granted there is an inescapable genius to its command of 14-year-old girl psychology; its premise is that the hot, broken guy who breaks into your house to draw you while you sleep wants to wait until marriage until he nearly screws you to death on a feather bed.”

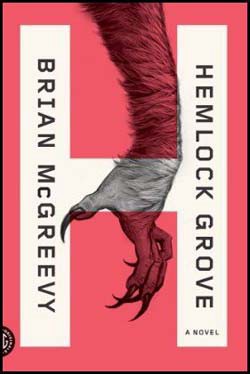

McGreevy’s new novel,

Hemlock Grove, published as part of the FSG Originals series, goes straight for the jugular, so to speak. Set in a Pittsburgh suburb, the novel centers on the grisly murders of teenage girls but the usual suspects, one werewolf and one vampire, are the least scary things stalking the sleepy little town. McGreevy lives in LA, where he’s also a screenwriter (right now he’s working on an adaptation of Dracula as well as one of his novel for Netflix). We talked by phone recently about what’s really scary, darkness and the best shaman in Park Slope.

Desiree Browne: How did Hemlock Grove get started?

Brian McGreevy: I was in graduate school at the time and there seemed to be a tendency to homogenize fiction. And I realized working in the mode of New Yorker-style writing — The New Yorker claims not to have a house style and it absolutely does — and I just realized I didn’t have an interest in that. That I wasn’t good at it, and that I should write about what I cared most about in the world, which tended toward blood and monstrosity. But at the same time I didn’t want that to be at the expense of psychological nuance and taking a certain amount of pleasure in prose as a medium.

This is stuff you were really into as a kid?

It’s stuff I’ve been into my entire life. I think everyone who’s being honest is into this kind of thing. In anthropology there’s a term they use called “the Jurassic Park syndrome.” It explains why monsters and predation are tropes that are extremely elemental to every storytelling tradition in every culture in history. The idea was that there was a huge amount of survival value to being intrigued by predators conceptually because it made you more likely to understand them. If you’re more likely to understand them, you were less likely to be killed by them — and then you could pass your genes along.

Did you believe that werewolves and vampires existed?

Fuck, I still do. I’m not exaggerating. If you look in the acknowledgments of the book, there’s one woman named Maja D’Aoust. She’s the self-described White Witch of Los Angeles. I can recommend a shaman in Park Slope. Her name is Mama Donna; her dog’s name is Princess Poppy. This is stuff that is not much of a stretch for me. I’ve had experiences where I had an ex-girlfriend that I knew was really mad at me and for no reason that the laws of physics could justify, a lamp would topple over in my room. I’ve had a sufficient number of occult experiences and synchronicities that to me it’s like love or orgasm. There are people who say, “yeah, people have orgasms” or “love doesn’t exist,” but once you experience it, it [love] actually does, and to me magic is more or less the same way. Once you’ve had an empirically indefensible thing happen to you, you now live in a world where that’s possible.

What’s your favorite Gothic novel?

It’s not the answer that most people would think. I would categorize One Hundred Years of Solitude as a Gothic novel. The Gothic novel has certain major tropes. For instance, an attraction to exploring extremes within the human condition manifesting light and darkness. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, you have profoundly evil characters doing profoundly evil things and then you have another character who’s literally so transcendental she ascends into the heavens. And then it culminates in an apocalypse. If that’s not Gothic, I don’t know what is.

Did you set out to change the vampire novel?

Not necessarily. I’m of the mind that you can’t really game the system, which is to say that you can’t calculate a creative project, per se. All you can really do is express the thing that is most exigent for you to express. There’s a metaphysics to syntax. So if you look at the phrase, “I was struck by lightning,” it’s like, yes, you were struck by lightning. It’s the reverse of “I had an a feeling.” What do you mean you had a feeling? You didn’t have a feeling, you didn’t decide to feel this way in this moment. Feelings happen to you the same way lightning happens to you. And really all you can do is to decide whether or not to go with it.

So no, I didn’t decide I was going to do something weird with the vampire novel. It was more, “here’s this weird-ass thing I want to do. It’s very compelling to me at the moment, it will be compelling to me for a number of years.” But then I started doing research and making creative executive decisions. One of those decisions was not to ever use the word “vampire” in the novel because I didn’t want the cultural freight of that word. I wanted to do something that was more mysterious and existed in a nebulous place where the light is coming from the darkness. In my research it was figuring out, “what’s the role for this? Oh, I’ve seen that a trillion times before and I don’t want to do that version of it.” It wasn’t me deciding “here’s what I’m gonna do,” it was retreating from what I found uninteresting.

Still, it’s obvious you did a lot of research and stuck to some conventions.

Well, the approach to research for this book was pretty funny because the first draft came out extremely, extremely quickly. I did a cursory amount of research going in and found out that there was this Slavic name for vampire, “upir,” so I used that instead of the word “vampire.” I learned about this concept of a vargulf, a werewolf that has gone insane and doesn’t eat what it’s killed. It wasn’t until after having written two or three drafts that I really went down the rabbit hole of research and just read dozens and dozens of books on various subjects that ended up informing the novel very significantly. But also, it was important to me at the time to not have this sense of purposefulness, in that the research I was doing was clarifying ideas I’d already had as opposed to introducing me to new ideas, if that makes sense. The biggest part of working on this book was figuring out how to articulate a series of preconscious ideas that the first two or three drafts consisted of.

What were some of those ideas?

Well, this concept of initiation, with both the two young male protagonists. The term “initiation” describes a ritual death and rebirth, which from the perspective of developmental psychology is this necessary rite of passage between the child self and the adult self. Both Peter and Roman in their perspective arcs of the book are going on to become the man they’re going to become. That’s something that’s of reasonably deep thematic interest to me because we live in what I would call a spiritually troubled time where, especially in coastal cities like New York or Los Angeles, it becomes difficult to identify when adolescence actually ends. I’ve lived in Los Angeles and met people who are middle aged who seem to be in an emotional state of adolescence.

There’s also such a dichotomy between religion and science. You’ll get dating profiles where they ask, “what are your religious beliefs?” and one of the categories is “spiritual, but not religious.” Are you fucking kidding me? They’re synonyms. That’s like saying, “I’m damp but not wet.” The empiricism of science is something that is very noble and reliable and in no way am I diminishing its significance, but there’s a place where its function ends. It’s the function of religion or spirituality or whatever the fuck you want to call it to answer the most significant questions that a strictly rationalist approach is not qualified to answer it. When people are on their deathbeds, they don’t ask to talk to a physicist.

But there’s not a lot of a religion in the book. Not in a very obvious way, at least.

Religion is something I certainly think about a great deal. My mother and father are both Presbyterian ministers. It comes back, to a certain point, to a definition of terms. When most people hear the term “religion,” their brains plug in the traditional. I have some interest in institutional religion from an anthropological perspective, otherwise I really don’t give a fuck. To me, the religious ideas that are in the book are much more primal and preagrarian, in a way. There’s natural balance to things, you exist in accordance with that balance and if you don’t you’re going to be punished. Not in some sort of Calvinistic way. You behave this way because it’s this natural flow of the universe and if you go against it, you’re going to suffer. Either in a manifest way or you’re just going to be so completely fucking unhappy there’s really no distinction.

Talk to me about your Vulture piece, which argued that “Don Draper is a far better vampire than any of Twilight’s or True Blood’s.” There were a lot of people that were really upset by the ideas you expressed there about what modern vampires should be. What in your view is fundamentally wrong with most of today’s vampires?

What the Vulture piece says I will essentially stand by. You don’t get to have your cake and eat it, too. When you have a female friend, and I have plenty of platonic female friends, they’ll date a guy and say, “Oh, yeah, there’s this guy I like. He’s great in every way but I’m not that interested in him.” Yeah, you’re not that interested in him because he’s being too nice to you and you know what his cards are. And then they’ll be dating this guy who’s kind of a piece of shit and they say, “He won’t text me back, he’s playing these games, he’s doing this he’s doing that and I’m really upset with him” and it’s like, are you fucking kidding? This guy is a bad idea. You’re completely oblivious to the virtues of the nice person and you’re completely obsessed with this guy who’s being a shitbag, and that tends to be pretty consistently true in my experience. So when you take this to a metaphorical level where in pop culture you say, “This guy is a bad idea on every level but actually it’s secretly because he loves you and it’s a really good idea and will commit to you”? That’s not how the fucking world works! This guy is a bad idea because he’s a bad idea. That was something that was very essential to me in committing to the adaptation of the novel [I’m doing for Netflix] with a character who’s very seductive. I didn’t want to morally whitewash him in anyway.

You really humanized the monsters for the most part in this book. We really get a chance to feel sympathy for them. Why was that important to you?

In depth psychology, which was very informative in the writing of the novel, there’s a term they use call “the uncanny effect.” It’s taking something that we don’t recognize in order to recognize ourselves more profoundly. And to me the premise of monstrosity is that it’s something that we find deeply empathetic and relatable, so what I had no interest in doing was creating a villain. And, at least from my own perspective, the novel doesn’t have a villain. There’s not a single character in that book that I personally can’t look at things from their perspective and think, “oh, well, yeah, I get where you’re coming from.”

Really?

Any one of them. This goes back to the idea of bourgeois sentimenality, which I have no real interest in advocating. People are very stuck in these proscribed ideas and values whereas the world is a lot fucking bigger than that and whether or not it’s something you endorse or that or how you choose to live your life, admit for a second that a lot of unpleasant things had to happen for you to live a pleasant life and that there had to be someone who said, “all right, this is the sacrifice that I am willing to make.”

Did you have any qualms about putting out a story this dark? Monsters aside, there’s a lot of scary stuff here.

I wrote the thing on Vulture that all these people were doing a shitty job for not being dark enough. I think there’s an honor to darkness, if I’m being frank. I think we live in a universe where the creative principle is as strong as the destructive principle. You can decide you’re not going to pay attention to this one thing at the expense of the other thing but then you’re half lying. Like, every baby that’s born has to die one day and I would say that’s fine. That’s actually kind of great. It’s a beautiful world that we’re a part of. The first has no value if you remove the other side of this equation. So you’ll say, you’re being really dark, but to me, the book also is a celebration of love.

Going back to determining what is the Gothic tradition, the Gothic tradition isn’t darkness per se, it’s looking at this polarity. How light is the light and how dark is the dark? In Hemlock Grove, the light is terribly brutally close.

What is monstrous in the novel?

The greatest degree of monstrosity is living inauthentically. If you take a model who weighs 97 pounds and is puking all the time and is doing a bunch of coke and is miserable, that to me is monstrous. Whereas if you get someone who is morbidly obese and is wearing nothing but Lycra and is like, “Fuck yeah, I’m hot shit” and believes it? That person’s a fucking hero. Because one is living authentically and the other isn’t. To me the monstrous characters in Hemlock Grove are the ones who are living inauthentically. Whereas characters that are literal monsters, they basically know who they are and how to live with integrity, which makes them not monsters in my estimation.

They have to hide a little bit.

Well, yes, that’s being an adult. Hiding is a conscious choice. I’m talking more people who don’t realize the self-deception in their lives. There was a Vimeo video that was being forwarded around my writing staff for the Netflix adaptation, a documentary about bestiality. There was a married couple being interviewed, a man and a woman, and the common bond between them was that both of them were being very honest and accepting of the fact they wanted to fuck a horse. And you’re watching them talk about this and I’m with my writers and I literally have tears in my eyes. It’s just so fucking beautiful, I want to punch myself. That is beyond great to me and sure, if they’re at a dinner party in front of a bunch of strangers they’re not going to say, “What brought us together as a couple was we both really like getting fucked by horses and when I see the bite marks from this horse on my partner’s back it just fills me with feelings of love and arousal.” You hide that for strangers but you still do it and you love that about yourself because that’s you and that’s authentic.

That’s, um, quite an example.

I stand by that example [laughs]. If you give me your email address, I’ll send you the link. Watching it, you’ll think, “This is one of the more unnerving things I’ve seen recently,” but there are plenty of people in heteronormative relationships that are fucking miserable and want to cut off each other’s heads. Joseph Campbell has a quote: “If you’re falling, dive.” So whatever is true to you, live that truth.

Desiree Browne asked her mom is she could have a séance at her thirteenth birthday party. Her mom said no and now she writes about less magical but still interesting stuff. Photo of Brian McGreevy by Rebecca Hickok.