In Defense Of Boredom

Did you read the excerpts from the forthcoming collection of Susan Sontag’s journals in the Times this past weekend? I really liked the part where she said, “Most of the interesting art of our time is boring.” I agree with that a lot. I don’t know if I’d say “most of,” but I like a lot of boring art, and boring things, and often find myself defending the benefits of boredom. (This post could quickly devolve into a semantical discussion of the precise definition of “boredom,” but I will elide that. I also liked the part in the article where Sontag said, “I don’t care about someone being intelligent,” for insecure selfish reasons.)

I don’t know as much about looking at paintings as I wish I did. Is Jasper Johns really “boring,” as Sontag said?

I guess I can understand what she’s talking about. Yes: more boring than, say, the terror induced by “Guernica” or “The Scream,” or the swirling ecstasy of “The Kiss.” Is Andy Warhol boring? Transfixed by the design of a soup can? Printing print after print after print at a place called The Factory? Yes, I can see it. Boring. And I very much like to look at the paintings of Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. The interestingness lies in the subtle change or glitch you find in a vast field of sameness. Or in contemplating repetition itself. (Or something?) And Sontag noted Beckett, too, as “boring.” And, sure, that seems like that was much of the point, at least from what I know. Boring and great. Vaclav Havel’s The Memorandum is like this, too. And maybe Passover and the best Jewish jokes, too.

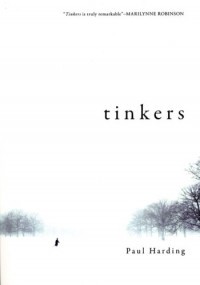

Definitely some of my favorite books might be legitimately described as boring. Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, famously about nothing more than a twenty-minute lunch break from an office in a Rochester mall — stops to buy shoelaces and a sandwich, a visit to the men’s room. Philip Roth’s Everyman, which tells a story of a not-so-extraordinary life. Paul Harding’s Tinkers, so slow and ruminative as it details the small moments and memories which make up the same for us all. I love it, but more than one person to whom I’ve recommended it brought back a verdict of “it’s boring.” And I can’t much argue that it’s not, even though it won the Pulitzer Prize when it was published, three years ago. It is boring, I guess. In a beautiful, and, to me at least, profound way. Tinkers reminds me more of Marilynne Robinson’s writing than anything else — its care in word choice and pacing elevating its sentences to poetry, lulling you into something like a narcotic state. It renders its gorgeous, rural-Maine setting exquisitely, too, and is a lot about death. Death can help anything hold one’s attention. But even the death is presented in a way that might be described as boring. Which I guess is nice, for death.

I think of Tinkers as a lot like the literature equivalent of the music of one of my favorite rock bands, a trio from Duluth, Minnesota called Low.

Low makes very slow, very simple rock songs, and sings them very quietly. The first time I saw them play a concert, at the Mercury Lounge, in 1996, the audience was so quiet, I could hear the flickering of candles mounted on the wall. After they played a cover of Joy Division’s song “Transmission” (which is funny because as the chorus exhorts you to “dance, dance, dance,” the tempo at which they played it made doing so impossible), the singer and guitarist Alan Sparhawk said, “This next song is just like the previous one. It starts with Zak on bass. Then I come in with a melody and start singing over some chords. Then Mimi joins me on the chorus. We don’t usually like to do two of these songs in a row, but tonight, we’re exposed.”

This is another funny little in-joke, because pretty much all of Low songs follow that format. I interviewed Alan soon after that concert for an article I wrote for ego trip magazine and he told me:

We wanted to experiment with some things that aren’t explored as often. We wanted to get away with as little as we could and see what we could pull off as a band playing as quiet as we could.

What Low explores, I think, and maybe the same can be said for Jasper Johns and Paul Harding, too, is the space between stuff. Action, excitement. The space between stuff happening. I suppose that’s the key to good, interesting boring art. When we’re bored into a state of looking for things to capture our interest, we find them — in unexpected places in the world around us and and maybe even in our own heads. (And maybe “lulled” is a better word here than “bored,” again the semantics.) Slowing our thinking down, as we look at, or read, or listen to something, is a wonderful gift an artist can give us. Especially in our increasingly speeding-up, over-stimulated world. Thank you, boring artists, for boring us!

(I would imagine the above could be said, and likely has been said, and probably more eloquently, about stuff like the minimalism of John Cage, or the drone of “no-wave” groups like Suicide or “shoegaze” rock. The Velvet Underground belongs somewhere in this discussion, surely, as does the one-note guitar solo Neil Young plays in “Down by the River,” which I often think of as an important moment in the genesis of punk rock. I know it has been said about Japanese art. The idea behind zen meditation being that you basically bore yourself into a sleep-like but observant state where mysterious inspiration can more readily strike. And this, a philosophy professor told me in a class I took in college, is the idea behind raking the sand in a rock garden with such perfect uniformity that the slightest gust of wind can come and cause a little deviation — and that’s where the beauty is found. And then you start raking it all over again. This is expressed in painting, too — the tiny glitch in an otherwise flawless image being the good part. Junichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadow is a good book to read about these ideas. I read that in that philosophy class.)

Okay, one last Low-is-boring in-joke: there’s a song on their second album, “Long Division,” called “Violence.” It’s one of their best songs, and sometimes at their concerts, people in the audience request it. It’s very funny to hear calls for “violence!” at concerts as still and staid as those that Low plays. Also, the only violence that occurs in “Violence” is the tearing out of pages from a dictionary.

Low is good music to fall asleep to. I could listen to it all day, and sometimes do.

Oh, this is also why I like baseball. Because it’s so boring. Tomorrow’s opening day! And I can not wait to be bored for the whole long, long, exquisitely dull, 162-game season.