How To Make Hard Apple Cider

How To Make Hard Apple Cider

by Willy Blackmore

I woke up hungover the other Saturday. It was just a mild headache, a low-level pain easily vanquished with a cup of coffee and a few glasses of water. But the hangover was special to me all the same, because I’d made it myself. The night before, a few months after buying five gallons of unpasteurized apple cider from an orchard east of Los Angeles, I got drunk for the first time off of my homemade booze.

This is how you make hard apple cider: simply put, do nothing. Apples are sweet, and their skins are covered with wild yeasts, giving you the only two ingredients needed to make alcohol. Yeast devours sugar and booze is born.

There are eight billion things that can be added to cider, and if you were to fall into the black hole that is the world of home brewers’ message boards (Exhibit A), you can read the various reasoning for adding sugar, honey, ascorbic acid, sulfites, yeast, heroin, nutrients, enzymes, and various other narcotic-looking powders. But when I cook a fucking steak, I season it with salt, and true to minimalist form, I added nothing to my cider. The juice was dumped into a plastic bucket I bought at the homebrew store and largely left to its own devices.

Booze made with one ingredient and no work may sound like the perfect recipe for broke, lazy drunks — and it is! — as long as you have patience. And there’s a bit of work to do along the way, like siphoning the nascent alcohol from one container to another every month or so, leaving behind the film of dead yeast and sediment that sinks to the bottom.

There’s also the rotten-egg state to be reckoned with, when sulfurous gas starts to leak out of the sealed fermenter, filling, say, the kitchen with the stench of rotting bodies. On those messages boards, homebrewers call these “rhino farts,” a name that’s really too kind.

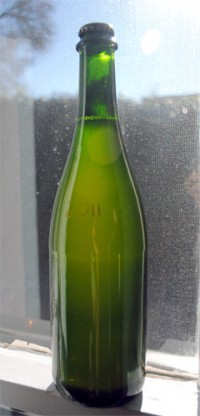

One more deterrent for lazy boozehounds thinking about getting all DIY: bubbles. Apple juice left to ferment for a few months will turn into something undeniably boozy, but it’ll be flat too. If the four or so percentage points of alcohol my cider weighs in at were easy to come by, carbonating it was far more difficult. It’s not that there’s a lack of bubbles involved in making booze — my cider was kicking off so much C02 that I practically knocked myself out cold after inhaling a cloud of it. It’s capturing that gas that’s the difficult part — the part that involves math, science-y measuring devices and the anxiety born of knowing that the two cases of 750 ml bottles full of cider sitting in your girlfriend’s closet could turn into so much apple-y shrapnel if things go wrong.

Here’s the gist of it: seal slightly sweet cider in a glass bottle, leave it the hell alone, and you’ll have a drink with some fizz to it in a few weeks. But if the cider is too sweet, if the bottles get too warm, if the glass isn’t strong enough… boom. The ten-foot arc of cider I sent spraying across a friend’s apartment when opening one bottle is as close to an explosion as I ever hope to come.

But catching a homemade buzz is an end that justifies the means only if the cider actually tasted good. And so: it smells a bit funky — like a horse, as one friend put it — and like yeast, too; the taste: tart and apple-y. It has none of the earthy, almost meaty depth of French ciders, or the intense tartness of Spanish ones. But it’s drinkable, which is all I was hoping for, and it was agreeable too.

The cider wasn’t the only batch of alcohol bubbling away in my apartment. There was a small lot of wine made from Grenache grapes grown near Ojai, too. And now every time I open a bottle of cider, I have to sacrifice a small, sparkling sip, one poured out in memory of its 2011-vintage brother, because that wine was an unmitigated disaster. Making wine was part of a larger project for me, one in which I grow up to be an old Italian man. So my attempt at winemaking followed my imagined school of old-man basement winemakers of the East Coast and Italy, one in which you just stomp on the grapes and don’t do — or add — much of anything else. My winemaking experiment cost a few hundred dollars — sixty pounds of grapes, a five-gallon fermenter and some other booze-making supplies. But that money largely went to waste, as I proved to be a grand failure of a vintner.

Pine Sol. Dry-erase markers. Burnt rubber. Tires. Eraser. These are just some of the lovely scents that wine had to offer. Having smelled and tasted the Grenache from its alcohol-free youth, before the various bacterial infections and attacks by ethyl acetylene turned it into something far worse than sour grapes, I know that there was something appealing about the juice — something the proceeding months completely obliterated. I’m afraid to even let it turn in to two gallons of vinegar.

If I try my hand at making wine again this fall, my approach will be less laissez-faire. But I won’t change the way I ferment my second vintage of cider — I’ll just make more of it. Those two cases of 750ml bottles are a stockpile that will be killed off after a month or so worth of spring picnics.

With this second round of cider I might be more ambitious in sourcing and pressing the juice, too. I’ve heard tell of an old, gnarled orchard of heirloom apples not far from L.A., and to buy part of the crop and pulp and press the apples myself would be ideal. But to do so would involve retrofitting the motor and blade of a garbage disposal to pulverize the apples and buying or building a basket press to extract the juice — far more work at a far higher cost than simply buying some juice and more or less ignoring it. I wouldn’t want to lose sight of the end-goal of making booze at home, namely, actually getting drunk off your own supply.

Willy Blackmore is the Los Angeles editor for Tasting Table. He has a Tumblr.