The New And Improved Thomas Jefferson, Enlightened Slave Owner

The New And Improved Thomas Jefferson, Enlightened Slave Owner

by Leah Caldwell

When the Smithsonian exhibit “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty” opened this past January it was greeted with a great deal of praise. A review in The New York Times called the exhibit “subtle and illuminating.” The Washington Post described it as “groundbreaking.” The hype surrounding the exhibit was understandable. This opening marked the first time that a museum on the National Mall has prominently acknowledged the fact that Thomas Jefferson owned 600 people in his lifetime.

The exhibit will be open through October, and on a recent weekend visit, it presented a picturesque scene of civic engagement, the horseshoe-shaped hall crowded with visitors, most of whom appeared to be from out of town. The crowd shuffled along slowly. Not far in, a young girl, white, about seven years old, paused in front of me and read a placard situated at child’s eye-level: If you were enslaved, would you run away? Two elevated panels next to the question presented her with the options “Yes” or “No,” in the style of a choose-your-own-adventure. She flipped up the “Yes” panel and the words seemed to snap back at her, complicating her choice: “What about your friends and family that you’d never see again?” She lifted the “No” panel, which revealed a terse, open-ended “Why not?”

Her dad remarked, “Pretty tough choice, huh?”

About 20 minutes later, I saw an older black woman, maybe 60 or so, drag her companion over to the same placard, asking him if he had seen this yet. They scanned the display and laughed; she said something to him under her breath, and they moved on.

“Would you run away?” was not the only question posed by the exhibit. Further on, another placard asked: If you were a black person with very light skin and could pass for being white, would you? Answer “No” and you’re presented with the following: “What are the benefits to being a person of color?” The hypotheticals had veered into territory reminiscent of educational Underground Railroad video games, but with the central characters now being Jefferson’s slaves.

Just a single line — set in a 24-point-sized font that you might easily miss if you weren’t looking — acknowledges that it’s “likely” that Jefferson fathered four of Sally Hemings’ children.

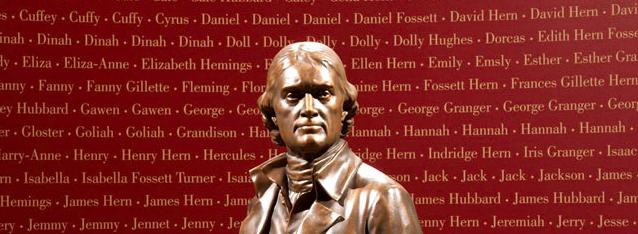

The names of these slaves are displayed prominently along a wall, painted a deep red, that curves around a statue of Jefferson when he was young. At least 600 people were enslaved at Monticello during Jefferson’s life, and for this exhibit, researchers have painstakingly pieced together some of their family trees and personal histories in an effort to reconstruct what their lives were like, at Monticello and after.

One of the displays near the back of the exhibit is dedicated to the Hemings family. This history was perhaps read more closely by most, although if you didn’t know anything about American history you might be confused as to why. Just a single line — set in a 24-point-sized font that you might easily miss if you weren’t looking — acknowledges that it’s “likely” that Jefferson fathered four of Sally Hemings’ children.

Lonnie Bunch, who co-curated the exhibit, has said that scholars have known about Jefferson’s “relationship” with Hemings for a long time, but “the public is still trying to understand it.”

Here is what the public is trying to understand: When Sally was 14, and a slave at Monticello, she accompanied Jefferson’s daughter, Polly, on a trip to France in 1787. Jefferson was about three decades her senior and widowed. She lived in France for two years, returning alongside Jefferson after the French Revolution. Their “relationship” turned sexual either in France, when Hemings was about 16, or upon their return to Monticello. Sally herself was born not far from Monticello. She was Jefferson’s wife’s half-sister, having been born to John Wayles, Jefferson’s father-in-law, and Betty Hemings, who was enslaved on Wayles’ plantation.

Until at least 1998, many of Jefferson’s biographers rejected this narrative. As biographer Joseph Ellis said in his 1997 book American Sphinx, this type of affair would have “defied the dominant patterns of his personality.” But once DNA evidence confirmed that Jefferson had “likely” fathered several of Hemings’ children, the dissenting views became the province of groups like the Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society that vows to “stand always in opposition to those who would seek to undermine the integrity of Thomas Jefferson.” In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which runs Monticello, released a report stating that there was a “high probability” that Jefferson fathered six of Hemings’ children, even though the current exhibit puts the number at four.

If anything, it’s not that the public has had trouble “understanding” the affair, it’s that many scholars and public institutions have been blocking the view.

In other words, what the exhibit is disclosing in 24-point font is a fact that first appeared in print in the early 19th century. And yet what’s odd about “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty” is how quickly acknowledgement shifts into full embrace. With the exhibit, Jefferson is reborn into yet another incarnation, that of the Greatest Gentleman Slave Owner of the United States. Knowing that Jefferson owned slaves helps us gain a “more comprehensive understanding” of the man himself, says a Monticello curator. At the Smithsonian blog Around The Mall, a write-up of the exhibit explains that “understanding Jefferson’s own complexities illuminates the contradictions within the country he built.” In this way, slave-ownership is quickly reduced to an attribute of a deeply conflicted, complex Jefferson.

“Paradox of Liberty” is a partner exhibit between the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and the future National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opens in 2015. Bunch, the museum’s founding director, has said

that the “Paradox of Liberty” is just one of several feeler exhibits that will help the future museum gauge public reaction to such difficult subjects as slavery. In addition to his role as the museum’s director, Bunch is an author and respected academic. His 2010 collection of essays, Call the Lost Dream Back, includes an anecdote that recalls a childhood baseball game in the 1960s. A group of white kids turned against him, hitting him with a bat, and pursuing him on foot. Running away, Bunch thought, “this is what it must have been like for a runaway slave.”

A youth guide to the exhibit reads “O is for Overseer. To help manage his property, Jefferson hired overseers to supervise the laborers and work being done.”

However laudable the goals of “Paradox of Liberty,” it doesn’t bode well that if you entered the Jefferson exhibit not knowing what slavery was, you might come out thinking it was an intensive training program for highly-skilled craftsmen. Each of the families discussed is given an association with a specific trade, like nailery or joinery, but mentions of overseers and brutality are scarce. One mention of a rough overseer is equivocated by mentioning, in the same placard, that Jefferson was against harsh treatment of slaves. A youth guide to the exhibit reads “O is for Overseer. To help manage his property, Jefferson hired overseers to supervise the laborers and work being done.”

The racial split of the crowd during the few hours I was there was maybe 70 percent white, 30 percent black. And at least some of the visitors, including some young enough to be relying on that youth guide, seemed to have a take on slavery that exceeded the exhibit’s content. “Whites were evil,” a white boy, about eight and wearing a Knicks jersey, said to his dad. “Yes, for a period of time, the whites were evil,” his dad responded. The boy and his siblings made their way to the giant model of Monticello. “Are these slavery camps?” the same boy asked. “It’s called a plantation,” the dad said. The boy immediately responded, “Isn’t that the same thing as a slavery camp?”

A few steps from the model, a glass case displayed Jefferson’s spectacles and a text by Herodotus, evidence of the claim that Jefferson was a man of the Enlightenment. It is only once visitors pass this gauntlet of Jefferson’s enlightened knickknacks do we reach the exhaustively researched stories and mapped-out lineages of the enslaved families of Monticello. A black man in his twenties, looking in the glass case with Jefferson’s spectacles, quipped sarcastically, “My question is: Just how enlightened was he? He was a slave owner.”

In his review for The New York Times, Edward Rothstein lauded the exhibit for its willingness to let the visitor make sense of the gap between Jefferson’s ownership of slaves and his “ideals.” But he was not all praise. About an exhibit placard which states Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence “did not extend ‘Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness’ to African-Americans, Native Americans, indentured servants, or women,” Rothstein said it “pushed too far.” This is “political boilerplate,” he said, continuing, “each of those cases needs different qualifications and examinations. They distract from the subject.”

Even though this exhibit is devoted to the stories and histories of the enslaved families of Monticello, Rothstein wrote that Jefferson’s achievements still must be seen “whole” and that “right now the exhibitions need a more deliberate elaboration of his ideas and life.” Rothstein explains that, yeah, Jefferson owned slaves, but we have to give credit where credit is due. “If slavery was, throughout global history, the rule, the exception was the last 200 years of gradual worldwide abolition. And Jefferson, for all his ‘deplorable entanglement,’ helped make it possible.”

After reading Rothstein’s critique, I found myself thinking of the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum in Baltimore. Built in 1983, the museum mostly hosts wax figures of prominent black politicians, astronauts, and revolutionaries, but visitors are more likely to remember two particular exhibits. One is the recreation of a slave ship at the entrance to the exhibition hall, where among other horrors, a model of a naked woman is chained to the ceiling with whip marks on her body. The next is the lynching exhibit in the basement. Newspaper clippings, poems, and song lyrics document the horrific and common tales of lynching in the US. Inside a glass case, papier-mâché-like figures remain fixed in the scene of a brutal lynching. A pregnant black woman has had her womb ripped open, her baby removed and replaced with a cat.

Back at the Smithsonian exhibit, there’s a display dedicated to the nailery at Monticello where enslaved men made nails. Children are encouraged to lift a 10-pound bucket of nails since a slave at Monticello, on average, would make 10 pounds of nails a day. “Can you imagine having to do that every day?” a father asked his daughter. She didn’t respond, but used her full body weight to lift the bucket about an inch from the ground.

On the way out the visitor is presented with another wall of names, a sign thanking the donors who have contributed at least one million dollars to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a list that includes: Boeing, the Oprah Winfrey Foundation, Bank of America, Walmart and Target.

Leah Caldwell is a writer at Al-Akhbar English.