The Poetry Of Ally Sheedy: A Look Back

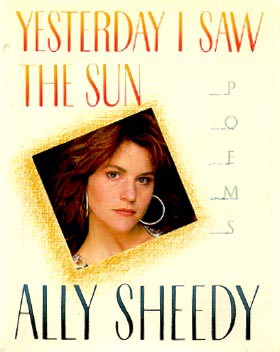

February marked the twenty-first anniversary of the publication of a book of poems by the gifted actor Ally Sheedy. It was called Yesterday I Saw the Sun, and she was famously excoriated for it. Sheedy was then 28 years old and coming off a very bad patch, including a stint at Hazelden; she had picked up an addiction to Halcion during an ill-fated fling with Bon Jovi guitarist Richie Sambora, and her friend Demi Moore is said to have scooped up the remains of Sheedy and posted them to rehab by way of an intervention. Terrible business, but the braying press went after her anyway. “Ally Sheedy from bad to verse,” yodeled the Post, and so forth.

There were kind reviews as well, though these did not come from the most distinguished literary critics. Larry King, for example, wrote in USA Today:

Ally Sheedy is a wonderful poet. A collection titled Yesterday I Saw the Sun ($14.95) has just been published by Summit Books and is really moving. Ally told me she wrote the poems during various stages of her life since age 12. This is an extraordinary mind at work.

King’s praise notwithstanding, Sheedy instantly became the poster girl for unbearable celebrity poetry. Years later, in 1994, Spy was still letting her have it. “Yeats, Millay, Browning, Sheen? Or, better yet — Sheedy?” The thing is, though, the story of how this book came about is far, far weirder than it looks at first blush.

***

Before we launch into the strange tale of Sheedy’s long history as an author, you may like to know something about this historic volume of poetry. Regrettably, I am a poetry idiot (preferring as I do Edward Lear to practically every poet except for Alexander Pope) and so I consulted the poet and essayist Jim Behrle for guidance on the true literary merits of Sheedy; I sent him the poem “New Jersey,” chosen at random from the subject volume, and asked his opinion. Here is how the poem opens:

New Jersey

Silver Lake

float away my dreams

slicing through your waters

in a conscious jet-ski stream

rolling toward your ocean

on the swells of movie themes

my mind has come apart

finding liberation in extremes

And it concludes thus:

Lost in the twilight somewhere in New Jersey

I dream new worlds to life inside

With the rise and fall of every breath

I feel much more

I fear much less

and late last night my old world died.

And I watched it go. And cried.

Behrle responded:

Many of my favorite poets are from New Jersey. Joe Ceravalo. Ginsberg. Jacqueline Waters. Snooki. So it doesn’t surprise me that Sheedy chooses the Garden State to speak to this particular emotion of being neither truly alive nor dead. Sheedy is the Wallace Stevens of celebrity poets. And just as I continue to wonder about the jar from Tennessee and what it’s supposed to mean I think I will wonder at the image of the jet ski all my days. That image will haunt me. With the path of froth that cuts across all dark souls. Many poets think they’re too clever or too cool to rhyme. Sheedy comes with no pretensions as is her way. “Liberation in extremes” obviously invokes Baudelaire. Even the sky is touchable and alive beneath her deft pen. In this poem we all get to feel “much more.”

This critique strikes me as simultaneously fair, generous and comically pleasurable, which must surely be the best way to read poetry. What should we expect of a young and famous actor who has just cracked up and landed in rehab? Something just like this. If it is hackneyed that is almost to be expected. If we follow Behrle’s lead and accept this work on its own merits and in a genial spirit, there’s surely more to be gained than by empty mockery, which, in any case, has already been done to death.

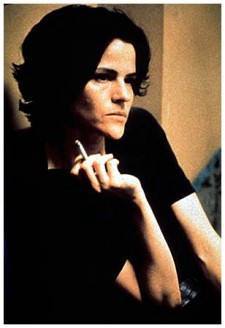

I am a huge fan of Ally Sheedy’s acting. Her performance in The Breakfast Club gave that feather-light movie a little bit of believable heft; she seemed capable of genuine emotions like grief and distress, rather than just tantrums. Her subsequent career had rollercoaster ups and downs (notably a disastrously-received performance in the stage version of Hedwig and the Angry Inch.) But her career was jumpstarted again in 1998 by a first-rate performance as a druggy, skeletal lesbian photographer in High Art. She is majestic and haughty, Sontagesque, in this film. (Both Sheedy’s mother and Sheedy’s daughter are lesbians, and she’s been a strong and effective advocate for LGBT causes.) To say nothing of her scorching performance in Todd Solondz’s Life During Wartime — the pen quails before the magnificence of that movie, which is total.

***

Part of the reason Yesterday I Saw The Sun was taken down so hard was its dissonance with the cultural mood at that time. This was the hangover of the Reagan era, rather like the hangover we are experiencing now from the Bush one, when our obsessions with materialism, wealth and self-centeredness were giving way to the (sadly, temporary) realization that none of this stuff was any use. The book came out in 1991, the same year as Nevermind; millions would soon be in the thrall of the anarchic, indeed somewhat Occupy-like message of Kurt Cobain, the real poet of that era. It wasn’t the moment for poetry written by a Hollywood actress in rehab.

***

The circumstances in which Yesterday I Saw The Sun were published are… complex. For starters, Sheedy’s mom, Charlotte Sheedy, is an eminent literary agent — an eminent literary agent who was, at that time, representing her daughter. Shortly after its publication, Entertainment Weekly asked Charlotte Sheedy to comment on the bad press her daughter’s book had received.

‘’I have 250 clients,’’ Charlotte Sheedy says. ‘’She’s just one of 250. And I say to her exactly what I say to every other client: ‘You write because you want to. Publishing was a decision you made. And people who respond to it have a right to their own opinion…’ I guess you think that’s not very sympathetic, but that is my attitude.’’

(I do, yes, I totally do think that’s not very sympathetic.)

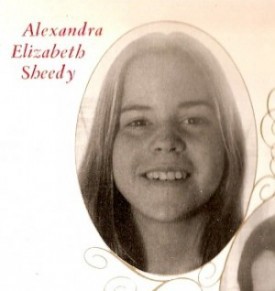

And THEN we learn that Yesterday I Saw The Sun wasn’t even Sheedy’s first published book. That had come in 1975, in the “novel,” as it was called: She Was Nice To Mice: The Other Side of Elizabeth I’s Character Never Before Revealed by Previous Historians, the utterly bizarre, meandering 95-page story of a bunch of mice who hung around with Queen Elizabeth I. The book was marketed on the adult list, for reasons that escape this reader. The author was twelve years old at the time of publication. Her best friend, Jessica Ann Levy, did the book’s illustrations.

Alexandra Sheedy, as she was then known, became something of an author-celebrity. She Was Nice To Mice was excerpted in Seventeen; Sheedy made a number of TV appearances, including this one on To Tell the Truth, a panel game show wherein she emerges as a grave, lovely, self-possessed kid, describing the genesis of her book with a hint of the same brooding intensity that would one day characterize her movie acting.

The idea of To Tell the Truth was that the unusual occupation of a person would be described and then three contestants appeared, each claiming to be that person. The panelists, all of them very witty and quick, were then required to identify the “real” one, based on a few moments’ questioning.

It is heartbreaking the way the wee Sheedy talks about Lytton Strachey, pronouncing the Bloomsbury maniac’s difficult surname correctly (“stray-chee”) but bungling his Christian name (“lie-ton”).

Questions naturally arose about Sheedy’s authorship of the book. How much of it had her mom/agent written? The most complete answer to this question came in an interview with the Los Angeles Times following the book’s release. Titled “A Mouse-Eye View of History,” the article was accompanied by a photo of mom and daughter gazing pensively into the distance. When the touchy question of authorship arose, Alexandra replied:

A lot of people say I didn’t write it. That hurts me. My mother just typed it. But if she couldn’t read it or if something didn’t make sense, she’d discuss it with me. She never changed anything without asking me. And we always discussed certain things if she didn’t think they were right. And then Joyce Johnson (of McGraw-Hill) edited it like she does all books.

Okay, but how did this kid aged twelve come to write this thing? Is she even really so driven, or is it the adults around her that are so driven? Who was really cooking up all this publicity? Are the adults making a novelty of this kid and if so, why?

And finally, the big question: was the book any good?

Well, no. It is fascinatingly terrible. She Was Nice To Mice is, among other things, a peeping-mouse erotic narrative, in which Queen Elizabeth I is depicted as a sex-crazed all-caps-screaming virago who also hides a herd of her mouse pals under her many skirts so that the ratcatcher won’t find them, including the narrator of the story, the queen’s special mouse friend, a distant ancestor of the Esther Long Whiskers Gray Hair Wallgate the 42nd with whom the book opens.

QEI gets naked at one point (bald, too, and with no makeup) and then the Earl of Essex pops out from under the bed, where he’d been hiding for a while. Sheedy is far more explicit about this possibility than is Strachey, I must say, in Elizabeth and Essex: a Tragic History.

“Come,” she said and took his hand and kissed it! And then she embraced him. She led him to the bed smiling. Elizabeth gracefully sank onto the silken cover.

Essex sat on the edge and took his boots, jacket, shirt and stockings off. He stood up and removed his pants and was there in his underwear. Then he turned, and went about the room blowing out the candles.

It was very dark now and I couldn’t see anything. But I heard.

Elizabeth said to him, “You have a strong body, my love.”

And Essex said, “Have I, now? You really think so?”

The sketchy, desultory, eye-crossing narrative follows things out to the beheading of Essex, but Francis Bacon doesn’t appear in it anywhere; also, there’s a really spurious-seeming love affair cooked up between Essex and Lady Arabella Stuart, and the mouse narrator keeps popping in with asides such as, “meanwhile I amused myself by jumping over all the noble feet.”

But the book sold well; 120,000 copies by 1998, according to Us magazine.

In June of 1977, when Sheedy was fifteen, a piece on “A Young Writers Salon” appeared in the Times describing The Children’s Literary Group, a gang of about two dozen would-be authors ranging in age from 10 to 17. This “salon” was held “at Charlotte Sheedy’s place on West 86th Street in Manhattan.”

They are the sons and daughters of book publishers, writers, editors, poets, lawyers, publicists, artists, teachers and psychiatrists, but above all, adults who love words.

“It might sound a little braggish,” says Daniel Pinchbeck, a dumpling-shaped 10-year-old with a broken front tooth […] “But most of the kids’ mothers are in publishing and we’ve been subjected to more literature and stuff — more knowledge of books.”

(And we thought our generation was especially beset with the super-ambitious Tiger Mothers and Helicopter Parents!)

***

When she was just twelve, right after her first book had come out, Sheedy wrote a piece for the New York Times, “Dolls for Adults,” a roundup of recently-published books about dolls and dolls’ houses, which begins, “When I was younger I remember being just captivated by dolls.” Her mother, Sheedy goes on to say, though a grownup, had four precious porcelain dolls (“an elegant one in silk, a bride, a servant and a princess.”) “… [M]y attraction to those four beautiful dolls grew and grew, and finally one day, I was allowed to hold them. Of course,” she writes, “the inevitable happened. One slipped from my hands and broke, and my mother began to scream, which was also strange because she was making such a fuss over a doll.”

***

In attempting to understand the idea of “stardom” and its place in our culture, I often return to Russell Brand, who explained the whole business to Jeremy Paxman concisely and, I think, correctly during this “Newsnight” interview.

Jeremy Paxman: What happens when [fame] arrives?

Russell Brand: What happens is that you have the initial thrill of achievement — oh my word! — the same as if you’d acquired a pair of shoes that you’d long craved, and then you realize that the shoes are too tight, they ain’t that comfortable, I want another pair of shoes, walking around in these things ain’t the same as I thought it would be. And you realize that you need nutrition from a higher source, something more valuable. Celebrity in and of itself is utterly, utterly vacuous, is tiresome.

How are you supposed to even dream of all that, when you are a kid?

Josh Rottenberg wrote a really good piece about Sheedy for Us in 1998, revealing the actor’s principal motivation as a young person.

At 12, she published She Was Nice to Mice, an elaborate children’s book about Queen Elizabeth I as seen through the eyes of her trusted mouse friends. The book became a minor sensation, and the ambitious young author relished the attention, telling Interview magazine, “I want to be famous, very famous, even after I die.”

If you start out wanting “to be famous” at such an early age, do you ever break free of it? The broader question being, what are we doing to people?

***

In the event, Sheedy became most famous for her portrayal of a dandruffy proto-goth in The Breakfast Club, alongside Molly Ringwald, Judd Nelson and Emilio Estevez, all of whom would come to be identified with the Brat Pack, a group of then-young actors that also included Rob Lowe, Demi Moore and Anthony Michael Hall. This name is said to have been invented by journalist David Blum in a depressing New York magazine piece that understandably infuriated every actor mentioned therein. Blum portrayed them all as spoiled, pretty, vapid and insufferable. Of Emilio Estevez, he wrote: “Dozens of girlfriends, many of them groupies, latch on for brief affairs; his romance with actress Demi Moore (who is also in St. Elmo’s Fire) is off and on. He is living the life that any American male might dream of — to be young, single, and famous.” They invite Jay McInerney out, they go to the Hard Rock Cafe. They go to the Imperial Gardens (a very fun punk club that is no more.) They don’t like the crowds there, they ditch McInerney, they go to that awful Carlos ’n’ Charlie’s on Sunset. Nobody makes them pay for anything. Oh, it’s bad.

Many of these actors failed to fulfill their initial promise; many wound up on drugs and in rehab, as Sheedy did; others succumbed to the lure of climbing ever higher, as Demi Moore did. Sheedy broke with Moore, she has said, because Moore’s ambition drove her to further her career by means of becoming a “sex symbol,” something Sheedy was never willing to do — unsurprisingly, since her mom, who’d been so influential in Sheedy’s life, had been a very committed feminist. Rottenberg explained:

As a turning point, Sheedy recalls a bike ride the two took together in Sycamore Canyon, north of Malibu, in the spring of 1986. Moore had recently visited [Sean] Penn and Madonna, who had married the previous summer, at their home in Malibu. “Demi was talking about Madonna, and she said, ‘That’s what I want. I want that,”’ says Sheedy “I said, `What do you mean? You want all that money?’ Demi said, ‘It’s not just the money It’s the power. She has power, and I want power.’ It was an illuminating moment for me. I thought I knew her, and I realized I didn’t at all. […]

“The quickest route to power for an actress in Hollywood is to hook yourself up with someone who can put you in a good position and make yourself into a sex object,” she says bitterly. The fact that many hold up Moore, like Madonna, as a feminist icon for the way she has pursued and consolidated her power seems to make little difference to Sheedy.

It comes as a relief to know that the toughness at Sheedy’s core has survived so much intact. (But still, what are we doing to people?)

***

Rob Lowe’s memoir, Stories I Only Tell My Friends, excerpted last year in Vanity Fair, addresses (in shockingly fine style, too — here is one former Brat Packer, at least, who really can write like a house on fire) some of what these kids were, and are, going through: “I’ve had just enough success to keep me chasing the dream, but not enough to ensure a career. I promise myself I won’t be one of the deluded ones, being the last to know that my moment didn’t come, and that I should’ve hung it up long ago. I’m going to be 17 soon. Am I already a has-been?”

***

The following is an excerpt from the poem, “Vivien Leigh Always Looked Up” from Yesterday I Saw The Sun.

things are strange

driving down Sunset Boulevard

her friends’ faces

stare at her

from billboards

she used to travel through this city

knowing

not a soul

reveling in the special freedom

of complete loneliness

alone with no parts

missing

Related: Winona Ryder’s Forever Sweater

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.