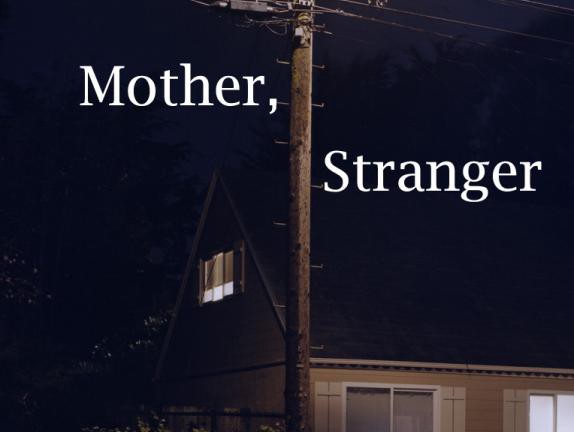

"Finding Out": From Cris Beam's "Mother, Stranger"

by Cris Beam

Cris Beam left her mother’s home at age 14, driven out by a suburban household of hidden chaos and mental illness. The two never saw each other again. More than twenty years later, after building the happy home life she’d never had as a child, Beam learned of her mother’s death and embarked on a quest to rediscover her own history. What follows is an excerpt from her nonfiction account, Mother, Stranger, published today by The Atavist. It is available as an ebook single for the Kindle, The Nook, the iPad or iPhone and other outlets via The Atavist website.

When I found out that my mother was dead, I was enraged. Not because she was gone — for that I felt a slight uptick of relief. I was angry because nobody had told me earlier. I hadn’t known she was sick, hadn’t known there was a funeral, hadn’t been able to say good-bye. I had never known how to talk to my mother, but I wanted to say good-bye.

A lawyer had found my brother first to broach the news, and my brother had called me. This lawyer wanted us to sign some papers, but I called him directly to ask why no one in her family — in my family — had reached out to us. The lawyer turned out to be a friend of my mother’s. She had done his bookkeeping for years. He told me that the family didn’t know how to find us, his tone cool and professional. This, I said, was impossible. I am an author and a professor at three universities; a Google search of my name yields plenty of hits. For $1.95, you can see my last seven addresses and get a criminal background check thrown in for free. My brother has a website with an address and phone number on it. After all, the lawyer himself tracked us down.

The lawyer then said that my mother had written us letters to tell us she was dying and we didn’t write her back.

“Oh,” I said, stunned. “She wrote to us?”

I didn’t tell him that the few letters she had sent me over the years had been in direct response to mine, that she’d never mustered the courage to make contact on her own.

“The family didn’t think you cared,” the lawyer continued. “You didn’t write back to her letters, so why would you go to her funeral?”

“But I never got a letter,” I protested, sounding every bit the 5-year-old I felt like inside.

The lawyer knew her husband, Clem, and her sister. “Well, honestly, I think Clem and Phyllis thought you had already caused your mother enough grief in her life, why should you be allowed to cause any more?” he said.

In my mother’s will, I discovered, she had left the house for Clem to maintain his “health and standard of living.” After he passes, half the sale of the house will be distributed to her relatives: Mom’s sister and her sister’s two children are to receive a quarter, and my brother and I will collect an eighth apiece. In 20 years, I may get a hundred bucks out of the deal. The only other things she had to give away were two diamond rings. These she bequeathed to my cousin Kathy.

After I got off the phone with the lawyer, I decided to take the risk and track down Clem. I had never met him. I discovered that he lived in a house he had shared with Mom for 18 years in Benicia, a town 11 miles from where I grew up. I saw a picture of it on Google Maps: It was a one-story clapboard house, painted blue with white trim. Clem was 72, but when he answered the phone he sounded younger. Your mother, he said, was the nicest person he had ever known.

“Your mother loved you,” Clem said. “She cried over you all the time. She never understood why you never came and saw her. Birthdays especially.”

Clem confirmed the letters she supposedly wrote when she was sick, though he never saw them. He said she cried when she didn’t hear back from us. He said he didn’t know how to find us for the funeral. In fact, he said, “I didn’t know if you was even alive.”

There must have been 150 people at the funeral, he told me. Everyone loved her. I had done a real bad thing, leaving her like that, he said, but she was never angry — just the rest of the family was, for treating her so bad.

I remembered the way my mother had told her family that I was dead and wondered if they ever believed it. I thought how strange it was to be a ghost: solid enough for everyone’s projections to land and stick but too ephemeral to fight back. I also felt that Clem didn’t like talking to me.

She was the smartest person in town, he said. I sensed he was trying to get off the phone. “You really missed a lot not knowing your mother.”

What about our report cards and stories and drawings and photographs from when we were kids, I asked him. My mother kept all of these things in boxes labeled with dates. There was nothing to prove our childhoods with our mother, only the scattering of pictures of the visits with our dad that marked us growing up.

“No, no, we threw all of that stuff away,” Clem said. His voice was rushed. “She didn’t want it anymore.”

The depth of this loss stopped me cold. “Um, could I have a picture of her, something of hers?”

“The only pictures I got are the pictures of her and me, and they’re up on the wall.”

“Could I get a copy of that picture, just to see what she looks like?”

“No,” Clem answered, his voice firm. “I don’t got nothing.” He hung up the phone.

Cris Beam is an author and professor in New York City. She is the author of the young adult novel I Am J, as well as Transparent, a nonfiction book that covers seven years in the lives of four transgender teenagers, which won the Lambda Literary Award for best transgender book in 2008 and was a Stonewall Honor book. She is currently at work on a book about the foster-care system. You can find the full ebook of Mother, Stranger at The Atavist.