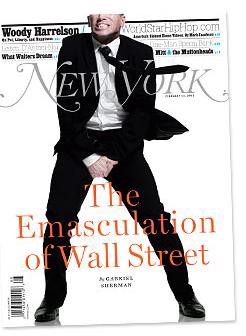

Dick Joke

Oh dear, here we go again: “Wall Street is a meritocracy, for the most part,” an irate but of course unnamed onetime Citigroup executive confides to junior father confessor Gabriel Sherman in this week’s hallucinatory New York magazine cover story, “The Emasculation of Wall Street.” “If someone has a bonus, it’s because they’ve created value for their institution.”

In the jumpy, suggestible universe of Gabe Sherman, Wall Street sleuth, things really are that simple: The beleaguered financial overclass creates value, in a rationally ordered system of maximally awarded talent. And the clueless public sector, intoxicated on post-meltdown regulatory prerogative, meddles with the primal forces of nature, skews executive compensation downward, panders to the blurry “populist” agenda of the Occupy Wall Street Crowd, generally foments market uncertainty and other forms of intolerable chaos so that presto, before you know it, we have “The End of Wall Street As They Knew It.”

In other words: To your crying towels, bankers! Correspondent Sherman is on the scene, and no howling distortion of recent financial history you care to offer is too outlandish for him to faithfully record! After duly huddling with a couple of dozen financial titans, our reporter has arrived at a chilling verdict: “what emerged is a picture of an industry afflicted by a crisis it would not be flip to call existential.”

Perhaps not — but what is exceedingly flip is brother Sherman’s account of the origins of the crisis.

Sure, there was that awkward business that sent the global finance sector to the brink of ruin, plus a devastating tsunami in Japan and whatnot — but the true culprit sending Wall Street titans back into their bedrooms to listen to Interpol on auto-repeat and cut themselves is of course the specter of government regulation. The Dodd-Frank financial reform act, a largely toothless measure lousy with loopholes and lobbying dosh, becomes in the alternate universe of Adam Moss’s New York magazine a rash bid to expropriate the expropriators. Even though the full provisions of the already anemic bill don’t go into effect until 2016, the very thought of a somewhat straitened financial playing field so terrifies Wall Street’s stout corridor of wealth creators that, well, they’re bidding farewell to the most valuable commodity of all — their big swinging dicks. “The government has strangled the financial system,” Dick Bove, an especially excitable and frequently mistaken bank analyst, tells Sherman. “We’ve basically castrated these companies. They can’t borrow as much as they used to borrow.”

You see, by force of the Volcker rule — a watered-down version of the central Glass-Steagall protections separating out commercial and investment banking that were disastrously repealed in 1999 — Wall Street is re-thinking everything, from the scale of its year-end bonuses to its “core value to the economy.” And Bove, for one, preaches that all this doom-and-gloom thinking can’t help but be self-fulfilling: “These are sweeping secular changes taking place that won’t just impact the guys who won’t get their bonuses this year. We’ve made a decision as a nation to shrink the growth of the financial system under the theory that it won’t impact the growth of the nation’s economy.” Another unnamed informant tells Sherman that the financial industry is gearing up for a state of near permanent pay-austerity at the mere thought of the Volcker rule, which doesn’t kick in officially until July: “If you landed on Earth from Mars and looked at the banks, you’d see that these are institutions that need to build up capital and they’re becoming lower-margin businesses. So that means it will be hard, nearly impossible, to sustain their size and compensation structure.”

Never mind that this diagnosis is diametrically opposed to the Bove-ian school of market alarmism, which holds that banks are being starved of desperately needed leverage and credit; this unnamed fearmonger sees them in a frenzy to raise capital, and one thing the Volcker rule undeniably seeks to achieve is minimal capital requirements to prevent speculative lending from veering once more into toxic chaos.

No, for Sherman, all that’s needed to stoke the proper mood of Misean panic is to rouse the specter of frightened bankers, and a few quick-and-dirty quarterly profit reports.

From the moment Dodd-Frank passed, the banks’ financial results have tended to slide downward, in significant part because of measures taken in anticipation of its future effect. Since July 2010, Bank of America nosed down 42 percent, Morgan Stanley fell 25 percent, Goldman fell 21 percent, and Citigroup fell 16 — in a period when the Dow rose 25 percent.

Other economic journalists might conclude that this downturn was a set of long-overdue market corrections, and given the broader turn around in the actual manufacturing economy, by no means an indication of worsening conditions — for investors and workers alike. Some radical others might even suggest that the shredded headcounts at the financial firms played a part in their own downturn in revenue. But while from his evidently privileged vantage in the driver’s seat of the Doc’s Time Machine, Sherman can divine all sorts of mischief arising from the yet-to-be-implemented provisions of Dodd-Frank, it does bear reminding that since 2010, BofA has been forced to eat a sizable portion of the toxic mortgage debt it acquired amid its spectacularly ill-advised purchase of Countrywide; Morgan has suffered tremendous losses in its Japanese operations and has, like most banks, been spooked by its exposure to the Euro-debt crisis (funnily enough, the firm’s US-based investment-banking operations — ie, the shop most directly affected by the dread Volcker rule, has booked profits amid all the tumult abroad); much the same general picture holds at Goldman, which as you may recall, has had more than its share of legal contretemps thrown into the bargain . As for Citigroup — the company whose very grotesque merged existence was the deregulatory excuse for repealing Glass Steagall — it’s been a basket case for so very long that a 16 percent loss in profits over the past two years seems cause for celebration, Volcker Rule or no Volcker Rule.

Indeed, for all of Sherman’s gullible huffing and puffing over the destructive reach of our new financial regulatory state, no one seems to have told the nation’s financial system this dire news, to judge by the actual behavior (as opposed to the opportunistic media rhetoric of its leaders). Yes, it’s been a rocky couple of years. And sure, Wall Street has lately shed plenty of jobs — who hasn’t? But in a report to investors inconveniently released one day ahead of Sherman’s dispatch from the existential trenches, Goldman Sachs — which continues to enjoy bullish stock performance amid its profit setbacks — announced this bit of non-emasculating news:

From a financial markets perspective, the environment looks quite friendly. The combination of better growth news and easier monetary policy is always welcome. In addition, we recently argued that corporate profit margins may still have room for further gains, despite the fact that they already stand at record levels from both a bottom-up and top-down perspective.

But no such merely empirical considerations can hope to stand up against the wrath of a stable of mainly unnamed bankers! Why, just look at Goldman itself, where Sherman reports that “months before the Volcker rule is set to kick in, star traders began [sic] to leave in droves.” And Goldman has lately shuttered its proprietary hedge-fund shop — in recognition that the line of essentially free credit that the Fed has opened up to investment houses may at last be about to dry up.

This, too, might well be seen as a sign of comparative health in the broader economy — especially with Goldman itself sounding so bullish on the investment climate, with the dread implementation of the Volcker Rule a scant five months away. After all, easy credit is what creates unsustainable bubbles in the first place, as even the most cursory study of the 2008 debacle shows. But not so in Shermanland! Even breakaway hedge shops are booking fairly lackluster profits (despite the obscene tax advantages they continue to enjoy) — so you know: Panic, everybody! Only Sherman is even less clear in explicating just what the cause for alarm is supposed to be in this case — while banks’ hedge-fund divisions are curtailed under the Volcker rule, hedge funds themselves need not tremble before its pending implementation. There’s the bad economy, yes — but it’s just as important, he insists, to note that the hedge sector is “as overbuilt as the housing and credit markets that drove its profits,” with the overall number of hedge funds exploding about 16-fold (610 to 9.553) from 1990 to 2011. One would assume that a slowdown in an oversupplied speculative sector is not, you know, a bad thing by itself, either — especially given that even the most diehard Randians would be hard-pressed to demonstrate that hedge funds create economic value of any kind. But Sherman nonetheless frets on behalf of hedge managers that “the easy obvious plays are oversubscribed, which shrinks margins…. Many have predicted a hedge-fund shakeout, and it seems to have started. Over 1,000 funds have closed in the last year and a half.” It’s evidently a taken-for-granted, second-nature kind of axiom in today’s American economy that an “industry” made up entirely of “easy obvious plays” is integral to our very survival.

Or at the very least, it’s a great enabling premise of lazy, overclass-osculating, dick-obsessed magazine journalism. Witness Sherman’s closing brief for the productive wonders worked by yon investment class:

It’s certainly true that Wall Street’s money played an important part in New York’s comeback, helping to transform the city from a symbol of urban decay into a gleaming leisure theme park. Consciously or not, as a city, New York made a bargain: It would tolerate the one percent’s excessive pay as long as the rising tax base funded the schools, subways, and parks for the 99 percent. “Without Wall Street, New York becomes Philadelphia” is how a friend of mine in finance explains it.

Well, Gabe, I have news for you and your friend in finance: For the vast majority of people living in the glorious and gleaming leisure theme park known as Michael Bloomberg’s New York, Philadelphia looks pretty goddamn inviting (and not just for delusional “sixth borough” hipsters). For one thing, the city’s schools have lately taken to looting state budget funds to make up for shortfalls; the city’s parks are already relying to a disproportionate degree on private donations to run themselves — except, of course, when the mayor wants to unleash city cops to displace and round up those irksome unproductive kids protesting wealth inequality. And do NOT get us started on the regressively funded, frequently inoperative subways, OK?

Then again, New York magazine is, God knows, a gleaming theme park all its own, and it’s perhaps best not to disturb the placid reveries of its well-appointed editorial brain trust. Yes, sustaining the enabling fictions of New York-style policy analysis does involve adducing sweeping assertions from the thinnest air: “The rising tide of the real-estate and credit markets lifted all boats,” Sherman burbles, apparently in reference to hedge funds, but a quick Google search for “Long Term Capital Management” will rapidly disabuse any civilian in the real economy of such a ludicrous notion. (And the ever-fallacious “rising tide” thesis is especially laughable when applied more broadly in today’s America.) Likewise, Sherman’s wind-up paragraph preposterously announces that “the strictures that are holding the banks back now are tighter than any since the thirties” — certainly news to any financial regulator of the mid-twentieth century, when off-shore mutual funds were heavily prosecuted and hedge funds were much more regulated (even without mandatory SEC registration); or to the economic policymakers of the Great Society era, who enforced corporate tax rates north of 40 percent, more than twice of today’s post-Dodd assessments. But why should we expect any other version of events from the hallowed precincts of Adam Moss’s TriBeCa wing of the great New York theme park? For as this week’s cover story plainly demonstrates, nothing can be considered real in this abject weekly’s pages unless it comes straight from the mouth of a banker.

Chris Lehmann is the co-editor of Bookforum and is the author of Rich People Things.