A Fresh Movement Against the NYPD's Culture of Misconduct

by Michael Tracey

New York City Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez had arrived on short notice to observe the sudden raid of Zuccotti Park on November 14th. But witnessing the removal of Occupy Wall Street’s original encampment proved impossible. Instead, officers forced Rodriguez to the ground, cutting his face; “a senior NYPD official with whom he has worked in the past was nearby,” the Village Voice reported.

At least ten journalists trying to cover that day’s events were arrested. Freelancers and people attempting to shoot video were threatened. Officers in riot gear hit demonstrators with batons, barring anyone from even approaching the park. Later, the New York Times general counsel wrote a stinging letter of complaint to the NYPD, co-signed by the Associated Press, local network television stations, and even the New York Post, which had openly mocked Occupy Wall Street from the beginning.

The NYPD’s aggressive, ad hoc approach to counteracting Occupy-related activities has attracted considerable attention since the demonstrations began. This has reanimated debate over the department’s day-to-day tactics away from Lower Manhattan. For some who have been harassed or arrested by police around Wall Street, the past few months have been their first personal experience treading the system at its least friendly — from rough arrests to being held overly long without arraignment. For some others, navigating the NYPD’s presence has long been a basic survival skill. The only thing that’s changed now? Demonstrators from privileged backgrounds are also getting a taste of the truncheon.

“That’s a good thing,” said Malik Rhasaan, co-founder of Occupy The Hood. “To be in the shoes of others. So you can see — ‘Wow, this is really going on. They maced a white girl out here, who did nothing.’ But that happens in my neighborhood all the time.” Founded in September as one of many OWS offshoot groups, Occupy The Hood’s aim was to enfranchise black and Hispanic communities within the broader Occupy movement. Early on, Rhasaan volunteered himself as a sort of emissary between Zuccotti Park and less glitzy areas of New York, where the reality of a “police accountability problem” goes almost without saying.

Born and raised in South Jamaica, Queens, the son of a former NYPD officer, Rhasaan has helped to facilitate the emergence of Occupy the Hood groups around the country — Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit — and translated the meaning of police-related grievances between culturally dissimilar groups. “I think we’re all like, ‘Now you see,’” he said.

Chief among activists’ concerns is the NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk” policy, which empowers officers to proactively detain people on the street at will. They are then encouraged to cite any number of vague pretexts — with “furtive movements” being a popular choice — as justification for a stop. The NYPD is projected to make 700,000 detentions city-wide in 2011. In 2002, only 73,000 were recorded. This spring, a WNYC investigation revealed that a large portion of stops were yielding arrests for petty marijuana possession, in violation of New York State law. Police Commissioner Ray Kelly was compelled to issue a directive, ordering that officers cease apprehending people who commit no infraction other than producing the drug after police instruct them to empty their pockets.

In some neighborhoods designated as “high crime” — which excludes Wall Street — “stop-and-frisk” has become the NYPD’s primary policing tactic. Consequentially, attitudes toward law enforcement are almost universally disdainful.

And system-wide police strategy becomes indistinguishable from individual misconduct. “My question is,” Councilman Jumaane Williams of Brooklyn said to me, invoking the popular cliched defense of police wrongdoing, “how many ‘bad apples’ does it take to make a bushel?”

Williams has also been roughed up by the NYPD, but earlier this year, at the Haitian West Indian Day Parade in Brooklyn. On their way to a function for city officials, one senior officer granted Williams and a colleague permission to enter a restricted area. Moments later, despite their repeated attempts to identify themselves, another group of officers wrestled both men to the ground and placed them in handcuffs. Police soon claimed — without merit, as it would later turn out — that an officer was punched during the episode. Williams said this was a “bald-faced lie.” The NYPD’s Internal Affairs bureau later sanctioned a captain, Charles Girvan, for his role in the altercation.

On November 3rd, Williams convened a press conference at One Police Plaza with State Senator Eric Adams and Assemblyman Hakeem Jefferies. The three warned of “a police culture that is being allowed to fester and grow,” Williams said. Senator Adams, himself a former police officer, called on the Justice Department to intervene and launch a federal probe.

“The NYPD is not accountable to anyone,” Williams told me. “That’s a very dangerous thing.”

In and around Zuccotti Park, demonstrators have become almost inured to arbitrary police intervention. People have been arrested for wearing bandannas, for using sidewalk chalk, and for standing in areas that can be deemed restricted at officers’ discretion. An NYPD panopticon unit still looms over the park, even post-eviction, surveilling occupants 24/7. But however disconcerting or over-reaching the NYPD’s tactics might be, they’re not even in the same realm as what goes on everyday in Harlem, Brownsville or Jamaica.

“The police in minority communities are accustomed to stopping anybody they want to stop,” said Ron Kuby, a civil rights attorney who has followed the NYPD closely for years. He’s now representing one of the women who was pepper-sprayed by Deputy Inspector Anthony Bologna in September during an OWS march to Union Square. “I know young people who have committed no crimes, who have done nothing wrong, who have been stopped five, ten, twenty times — before they get out of high school,” Kuby said. “That’s a regular occurrence for young men of color. And the police do it with impunity.”

* * *

So all this came together when, on October 22nd, a group affiliated with OWS set out specifically to protest the NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk” policy by way of nonviolent direct action. Around 150 people gathered in the center of Harlem for the first of its events. Things proceeded with a familiar Occupy feel — a General Assembly-type gathering, hand motions and “mic checks” all included. John Hector, a 25-year-old Navy veteran, addressed the group, telling of when he was subjected to “stop-and-frisk” after returning from Iraq.

“He decided he was going to be funny,” Hector said of the officer who had stopped him one night, “and asked us if we knew how to do the ‘chicken noodle soup.’ He asked us to dance for him. He said that was the only way we were going to be let go. It was humiliating, embarrassing, and I hate being represented like that in front of my community.”

Hector later marched with students, clergy, and criminal justice professors to Harlem’s 51st police precinct building, passing the iconic Apollo theater en route. “Bring back the Fourth Amendment,” one marcher’s sign simply read. Hector, who had no previous criminal record, was arrested when he and 35 others attempted to block the precinct building’s front entrance.

Richard Brown, another Harlem native who addressed the crowd that day, told me of his own experience with “stop-and-frisk.” As he walked home one morning in 2009 from his construction job, a plainclothes sergeant approached him in the street. Without warning, Brown said, the sergeant punched him in the throat, and within seconds he was on the ground. “I fit the characteristics of somebody else,” Brown said. “After they beat me down and realized I was the wrong person, they had to pursue the case.”

So when Brown arrived at the station, he said, “heroin magically appeared.” That, naturally, landed him at Rikers Island for 20 days. A judge eventually dismissed the charges and reprimanded the presiding officer, but Brown’s life was turned upside down. He’s now in the process of suing the city. “Ever since my case, I’m more aware of what’s going on with the police department,” Brown said. “I’m actually scared of them. I got beat up, man. I was bleeding. They wouldn’t take me to a hospital.”

* * *

Joanne Naughton, a former NYPD narcotics detective, told an audience at the New York City Students for Liberty Conference in October that the practice of planting drugs on suspects was not something she regularly observed over her 20-year tenure. “But when you have unenforceable laws,” she said, “it doesn’t surprise me.”

“Officers may do a frisk only if they have additional reasonable suspicion to believe a suspect is armed,” Naughton told me after the speech. “Not carrying drugs, but armed with a gun. I’m sure they don’t have reasonable suspicion to believe that everybody they stop — hundreds of thousands a year — is carrying a gun.”

“So these stops are illegal, unconstitutional, and in violation of New York State Law,” she said. “But the mayor likes it. It looks good, it looks muscular. It looks tough.”

The OWS-affiliated group’s next action was held in Brownsville, Brooklyn. The Times found that between January 2006 and March 2010, the NYPD carried out nearly 52,000 stops in a single neighborhood there — an area of just eight city blocks. Fewer than one percent of those stops yielded arrests.

Among those addressing the Brownsville rally was Gbenga Akinnagbe, the actor who portrayed Chris Partlow on “The Wire.” “We have to remember,” Akinnagbe told me as the group marched from the Marcus Garvey Housing Projects to the 73rd NYPD precinct building, several blocks away, “The police are doing exactly what they’re trained to do. So you have to go to the source.”

“It’s funny, people get angry at the police, but they’re just fingers to the problem,” he said. “They’re just symptoms. You saw down on Wall Street, when those kids got sprayed with mace? That shit was mild,” he said. “This happens here every day. Literally, every day.”

I lost track of Akinnagbe when we arrived at the precinct building; disparate crowds formed as those willing to risk arrest separated themselves out. Demonstrators again attempted to peacefully block the building’s entrance, as they had in Harlem. Police started taking people into custody. Then I saw Akinnagbe. He was handcuffed, and he smiled as officers loaded him into an NYPD wagon.

The “stop-and-frisk” group’s third action took place in Jamaica, Queens, hometown of Rhasaan, the Occupy The Hood co-founder. “I was raised here, I have children here, I live here today,” he told the crowd gathered outside King Park. “I’ve also been beaten here, stopped here, and frisked here. I have friends who died at the hands of the police here.”

“This doesn’t have to stop now,” he said. “It has to stop right now.”

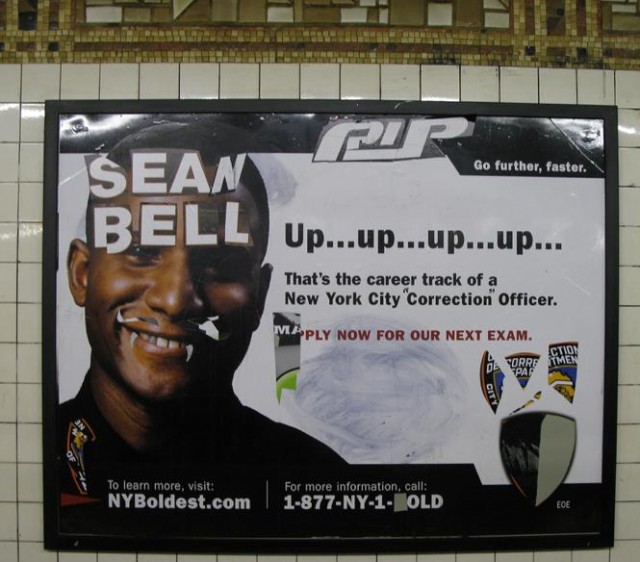

With Rhasaan at the head, a multiracial and multigenerational crowd of more than 100 people marched through Jamaica, headed in the direction of another NYPD precinct building — this time the 103rd. In 2006, undercover police based there shot fifty bullets at 23-year-old Sean Bell and two friends, killing him on the eve of his wedding. The officers responsible were acquitted, and five years later, the surrounding community still reels; chants invoking Bell’s death broke out intermittently along the march.

As we passed throngs of pedestrians going about their Saturday afternoon routines, some were initially confused at the sight of white people marching alongside blacks and Hispanics through the heart of Jamaica. But when they heard demonstrators talking about “stop-and-frisk,” about Sean Bell, about abuse at the hands of the NYPD, it didn’t take long for something to click. “Damn, I can get behind that!” one onlooker said. He pocketed a “stop stop-and-frisk” leaflet, after showing it to a friend.

The man’s sentiment — instinctive hostility to the police — seemed utterly ubiquitous. Everyone in these parts of the city has a story involving an abrasive officer and a cousin, or a neighbor, or themselves. This typically breeds cynicism and disillusionment — and from time to time, the anger and mistrust gets politicized. Recently, more have come to recognize that police abuse is not just some minor nuisance, but a critical component of a legal and political system that routinely degrades the dignity of citizens who happen to live in blighted urban areas.

About halfway through the march, Rhasaan told the crowd to pause, and we did. He wanted us to look around, to really understand where we were standing at that moment. “I am your tour guide,” Rhasaan said. “And this the hood.”

* * *

Last Friday brought another meeting of Occupy Wall Street’s Spokes Council, the “governing body” that grew from the General Assembly in Zuccotti Park. (Working groups like Housing, Direct Action and Sanitation select a “spoke” to attend, and they deliberate proposals among the entire group.) “Stop Stop-and-Frisk” was as permanent a participant in the Spokes Council as, for example, Sustainability or Outreach, and the representative that night happened to be a white woman. Rhasaan was also there with the People of Color subgroup. “Stop Stop-and-Frisk” reported that its student-led march earlier that afternoon through Wall Street and some housing projects on the Lower East Side had been a success.

This relatively small group — bolstered by Occupy Wall Street at large — is having a big impact. That matters, because when politicians are asked to comment on police misconduct, of course, the platitude they most often trot out is some variation of the classic “just a few bad apples” rationalization. Wrong-doing committed by a small minority of individuals, the logic goes, ought not to tarnish an entire department’s good name. In recent weeks, New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg has demonstrated a particular fondness for this line of reasoning. But when an official department policy is at question, the “few bad apples” argument becomes manifestly incoherent.

The NYPD will undoubtedly set their record for stop-and-frisks in 2011. Couple that with the department-wide ticket-fixing scandal, its unprecedented harassment and arrests of journalists, internal allegations of sexual violence by female officers, interstate gun smuggling rings, straight-up racism — and, oh yes, that nighttime paramilitary-style raid on the symbolic center of a worldwide political movement, now formally requested to be the subject of a Department of Justice investigation — and you have a police situation in New York City that has gone awry system-wide. “Stop-and-frisk” embodies the NYPD’s methods of daily policing; “Stop Stop-and-Frisk” is the only appropriate response.

Michael Tracey writes for myriad publications, typically on matters of spiritual significance. Photo by Shira Golding.