A Conspiracy of Hogs: The McRib as Arbitrage

What the McRib says about us as a society is worse than any conspiracy theory

by Willy Staley

One of McDonald’s most divisive products, the McRib, made its return last week. For three decades, the sandwich has come in and out of existence, popping up in certain regional markets for short promotions, then retreating underground to its porky lair — only to be revived once again for reasons never made entirely clear. Each time it rolls out nationwide, people must again consider this strange and elusive product, whose unique form sets it deep in the Uncanny Valley — and exactly why its existence is so fleeting.

The McRib was introduced in 1982–1981 according to some sources — and was created by McDonald’s former executive chef Rene Arend, the same man who invented the Chicken McNugget. Reconstituted, vaguely anatomically-shaped meat was something of a specialty for Arend, it seems. And though the sandwich is made of pork shoulder and/or reconstituted pork offal slurry, it is pressed into patties that only sort of resemble a seven-year-old’s rendering of what he had at Tony Roma’s with his granny last weekend.

These patties sit in warm tubs of barbecue sauce before an order comes up on those little screens that look nearly impossible to read, at which point it is placed on a six-inch sesame seed roll and topped with pickle chips and inexpertly chopped white onion. In addition to being the outfit’s only long-running seasonal special and the only pork-centric non-breakfast item at maybe any American fast food chain, the McRib is also McDonald’s only oblong offering, which is curious, too — McDonald’s can make food into whatever shape it wants: squares, nuggets, flurries! Why bother creating the need for a new kind of bun?

The physical attributes of the sandwich only add to the visceral revulsion some have to the product — the same product that others will drive hundreds of miles to savor. But many people, myself included, believe that all these things — the actual presumably entirely organic matter that goes into making the McRib — are somewhat secondary to the McRib’s existence. This is where we enter the land of conjectures, conspiracy theories and dark, ribby murmurings. The McRib’s unique aspects and impermanence, many of us believe, make it seem a likely candidate for being a sort of arbitrage strategy on McDonald’s part. Calling a fast food sandwich an arbitrage strategy is perhaps a bit of a reach — but consider how massive the chain’s market influence is, and it becomes a bit more reasonable.

Arbitrage is a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets — it’s the proverbial free lunch you were told doesn’t exist. In this equation, the undervalued good in question is hog meat, and McDonald’s exploits the value differential between pork’s cash price on the commodities market and in the Quick-Service Restaurant market. If you ignore the fact that this is, by definition, not arbitrage because the McRib is a value-added product, and that there is risk all over the place, this can lead to some interesting conclusions. (If you don’t want to do something so reckless, then stop here.)

The theory that the McRib’s elusiveness is a direct result of the vagaries of the cash price for hog meat in the States is simple: in this thinking, the product is only introduced when pork prices are low enough to ensure McDonald’s can turn a profit on the product. The theory is especially convincing given the McRib’s status as the only non-breakfast fast food pork item: why wouldn’t there be a pork sandwich in every chain, if it were profitable?

Fast food involves both hideously violent economies of scale and sad, sad end users who volunteer to be taken advantage of. What makes the McRib different from this everyday horror is that a) McDonald’s is huge to the point that it’s more useful to think of it as a company trading in commodities than it is to think of it as a chain of restaurants b) it is made of pork, which makes it a unique product in the QSR world and c) it is only available sometimes, but refuses to go away entirely.

If you can demonstrate that McDonald’s only introduces the sandwich when pork prices are lower than usual, then you’re but a couple logical steps from concluding that McDonald’s is essentially exploiting a market imbalance between what normal food producers are willing to pay for hog meat at certain times of the year, and what Americans are willing to pay for it once it is processed, molded into illogically anatomical shapes, and slathered in HFCS-rich BBQ sauce.

The McRib was, at least in part, born out of the brute force that McDonald’s is capable of exerting on commodities markets. According to this history of the sandwich, Chef Arend created the McRib because McDonald’s simply could not find enough chickens to turn into the McNuggets for which their franchises were clamoring. Chef Arend invented something so popular that his employer could not even find the raw materials to produce it, because it was so popular. “There wasn’t a system to supply enough chicken,” he told Maxim. Well, Chef Arend had recently been to the Carolinas, and was so inspired by the pulled pork barbecue in the Low Country that he decided to create a pork sandwich for McDonald’s to placate the frustrated franchisees.

But the McRib might not have existed were it not for McDonald’s stunning efficiency at turning animals into products you want to buy.

As McDonald’s grows, its demand for commodities also grows ever more voracious. Last year, Time profiled McDonald’s current head chef, Daniel Coudreaut (I know what you’re thinking: two Frenchmen have been Executive Chef at McDonald’s? But no, Chef Coudreaut is American, while Chef Arend is a Luxembourger), whose crowning achievement so far has been turning a Big Mac into a burrito. In his test kitchen, we learn, a sign hangs that reads “It’s Not Real Until It’s Real in the Restaurants,” reminding chefs and cooks that their creations, no matter how tasty and portable they may be, must be scalable — above all else.

When the Time reporter visited the kitchen, Chef Coudreaut was cooking a dish that involved celery root — a fresh-tasting root that chefs love for making purees in the fall and winter. Chef Coudreaut proves to be quite a talented cook, but Time notes that “there is literally not enough celery root grown in the world for it to survive on the menu at McDonald’s — although the company could change that since its menu decisions quickly become global agricultural concerns.”

(Want to make enemies quickly? Tell this to the woman at the farmer’s market admiring the rainbow chard. Then remind her to blanch the stems a few minutes longer than the leaves — they’re quite tough!)

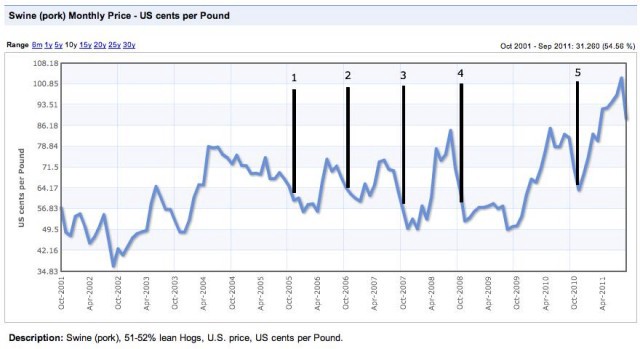

Now, take a look at this sloppy chart I’ve taken the liberty of making. The blue line is the price of hogs in America over the last decade, and the black lines represent approximate times when McDonald’s has reintroduced the McRib, nationwide or taken it on an almost-nationwide “Farewell Tour” (McD’s has been promising to get rid of the product for years now).

Key: 1. November 2005 Farewell Tour; 2. November 2006 Farewell Tour II; 3. Late October 2007 Farewell Tour III; 4. October 2008 Reintroduction; 5. November 2010 Reintroduction.

The chart does not include pork prices leading into the current reintroduction of the McRib, but it does show it on a steep downward trend from August to September. Prices for October, 2011 hogs have not been posted yet, but I suspect they will go lower than September — pork prices tend to peak in August, and decline through November. McDonalds, at least in recent years, has only introduced the sandwich right during this fall price decline (indeed, there is even a phenomenon called the Pork Cycle, which economists have used to explain the regular dips in the price of livestock, especially pigs. In fact, in a 1991 paper on the topic by Jean-Paul Chavas and Matthew Holt, the economists fret that “if a predictable price cycle exists, then producers responding in a countercyclical fashion could earn larger than ‘normal’ profits over time… because predictable price movements would… influence production decisions.” At the same time, they note that this behavior would eventually stabilize the price, wiping out the pork cycle in the process).

Looking further back into pork price history, we can see some interesting trends that corroborate with some McRib history. When McDonald’s first introduced the product, they kept it nationwide until 1985, citing poor sales numbers as the reason for removing it from the menu. Between 1982 and 1985 pork prices were significantly lower than prices in 1981 and 1986, when pork would reach highs of $17 per pound; during the product’s first run, pork prices were fluctuating between roughly $9 and $13 per pound — until they spiked around when McDonald’s got rid of it. Take a look at 30 years of pork prices here and see for yourself. Also note that sharp dip in 1994 — McDonald’s reintroduced the sandwich that year, too. Though notably, they didn’t do so in 1998.

(I’m sure all the sharp little David Humes among us are now chomping at the bit — and you’re right to do so! This proves nothing. It is just correlation — and the sandwich doesn’t always appear when pork prices are low. In fact, the recent data could prove that McDonald’s actually drives pork prices artificially high in the summers before introducing the sandwich — look at 2009’s flat summer prices. Could that be, in part, because there was no McRib? On the other hand, food prices were flat across the board in 2009 so probably not. So, no, this correlation proves nothing, but it is noteworthy.)

Because we don’t know the buying patterns — some sources say McDonald’s likely locked in their pork purchases in advance, while others say that McRib announcements can move lean hog futures up in price, which would suggest that buying continues for some time — and we can’t seem to agree on what the McRib is made of — some sources say pork shoulder, others say a slurry of offal — it’s hard to really make any real conclusions here.

The one thing we can say, knowing what we know about the scale of the business, is that McDonald’s would be wise to only introduce the sandwich (MSRP: $2.99) when the pork climate is favorable. With McDonald’s buying millions of pounds of the stuff, a 20 cent dip in the per pound price could make all the difference in the world. McDonald’s has to keep the price of the McRib somewhat constant because it is a product, not a sandwich, and McDonald’s is a supply chain, not a chain of restaurants. Unlike a normal restaurant (or even a small chain), which has flexibility with pricing and can respond to upticks in the price of commodities by passing these costs down to the consumer, McDonald’s has to offer the same exact product for roughly the same price all over the nation: their products must be both standardized and cheap.

Back in 2002, McDonald’s was buying 1 billion pounds of beef a year. (As of last year, they were buying 800 million pounds for the U.S. alone.) A billion pounds of beef a year is 83.3 million pounds a month. If the price of beef is abnormally high or low by 10 cents a pound, that represents an $8.3 million swing (which McDonald’s likely hedges with futures contracts on something like beef, which they need year-round, so they can lock in a price, but this secondary market is subject to fluctuations too).

At this volume, and with the impermanence of the sandwich, it only makes sense for McDonald’s to treat the sandwich as a sort of arbitrage strategy: at both ends of the product pipeline, you have a good being traded at such large volume that we might as well forget that one end of the pipeline is hogs and corn and the other end is a sandwich. McDonald’s likely doesn’t think in these terms, and neither should you.

But when dealing with conspiracy theories, especially ones you aren’t quite qualified to prove, one must always consider other possibilities, if only to allow them to reinforce your nutty beliefs.

Counter Theory 1: An obvious reason that the McRib might be a fall-only product could be that people have barbecue (or at least things slathered in barbecue sauce) all the time over the summer — they would be less likely to settle for a cheap and intentionally grotesque substitute when they can have the real thing. Introduce it in the fall and you might catch that associative longing for the summer that HFCS-laden spicy sauces and rib-shaped things evoke.

To this I say: but what about winter?

Counter Theory 2: Another counter-theory comes from an online forum, where all good and totally reliable information comes from on the Internet. Here, an alleged graduate from Hamburger University claims that the McRib’s impermanence has nothing to do with pork prices, but rather that it’s a loss leader for McDonald’s — the excitement of a limited-time-only product gets people in the door, as we have noted, and they’ll probably buy the big drinks and fries with the Monopoly pieces on them because they’re, on average, impulsive and easy to fool.

To this I say: I knew that sandwich was a low margin product! All the more reason for McDonald’s to time it properly with price swings.

Counter Theory 3: The last, and most obvious, explanation is the official version of the story: the sandwich has a cult following, but it’s not that popular. Like “Star Trek,” “Arrested Development” and that show about Jesus Christ returning to San Diego as a surfer, the McRib was short-lived because not enough people were interested in it, even though a small and vocal minority loved it dearly. And unlike these TV shows, which involve real actors and writers with careers to tend to, the McRib needs only hogs, pickles, onions and a vocal enough minority who demand the sandwich’s return, and will even promote it for free with websites, tweets and word-of-sauce-stained-mouth.

We’re marks, novelty-seeking marks, and McDonald’s knows it. Every conspiracy theorist only helps their bottom line. They know the sandwich’s elusiveness makes it interesting in a way that the rest of the fast food industry simply isn’t. It inspires brand engagement, even by those who do everything they can to not engage with the brand. I’m likely playing a part in a flowchart on a PowerPoint slide on McDonald’s Chief Digital Officer’s hard drive.

Ultimately what the McRib says about us as a society is perhaps worse than any conspiracy theory about pork prices. The McRib, born at the end of the Volcker Recession, a child of Reagan’s Morning in America, has been with us on and off over the last three decades of underregulated corporate growth, erosion of organized labor, the shift to an “ideas” economy and skyrocketing obesity rates. The McRib is made of all these things, too. When you think back to its humble origins, as both an homage to Carolina style pork barbecue, and as a way to satisfy McNugget-hungry franchises, it’s all there.

Barbecue, while not an American invention, holds a special place in American culinary tradition. Each barbecue region has its own style, its own cuts of meat, sauces, techniques, all of which achieve the same goal: turning tough, chewy cuts of meat into falling-off-the-bone tender, spicy and delicious meat, completely transformed by indirect heat and smoke. It’s hard work, too. Smoking a pork shoulder, for instance, requires two hours of smoking per pound — you can spend damn near 24 hours making the Carolina style pulled pork that the McRib almost sort of imitates.

And for its part, the McRib makes a mockery of this whole terribly labor-intensive system of barbecue, turning it into a capital-intensive one. The patty is assembled by machinery probably babysat by some lone sadsack, and it is shipped to distribution centers by black-beauty-addicted truckers, to be shipped again to franchises by different truckers, to be assembled at the point of sale by someone who McDonald’s corporate hopes can soon be replaced by a robot, and paid for using some form of electronic payment that will eventually render the cashier obsolete.

There is no skilled labor involved anywhere along the McRib’s Dickensian journey from hog to tray, and certainly no regional variety, except for the binary sort — Yes, the McRib is available/No, it is not — that McDonald’s uses to promote the product. And while it hasn’t replaced barbecue, it does make a mockery of it.

The fake rib bones, those porky railroad ties that give the McRib its name, are a big middle finger to American labor and ingenuity — and worse, they’re the logical result of all that hard work. They don’t need a pitmaster to make the meat tender, and they don’t need bones for the meat to fall off — they can make their tender meat slurry into the bones they didn’t need in the first place.

And unlike a Low Country barbecue shack, McDonalds has the means to circumvent — or disregard — supply and demand problems. Indeed, they behave much more like a risk-averse day trader, waiting to see a spread between an Exchange Traded Fund and its underlying assets — waiting for the ticker to offer up a quick risk-free dollar.

Witness to all this, Americans on both coasts tweet jokes about the sandwich, and reference that one episode of “The Simpsons,” and trade horror stories, or play the contrarian card and claim to love it; and meanwhile, somewhere in Ohio, a 45-year-old laid-off factory worker drops a $5 bill on the counter at his local McDonald’s and asks a young person wearing a clip-on tie for the McRib meal, “to stay.” The McRib is available nationwide until November 14th.