Inside The "Riot Grrrl" Archives

by Alex Carp

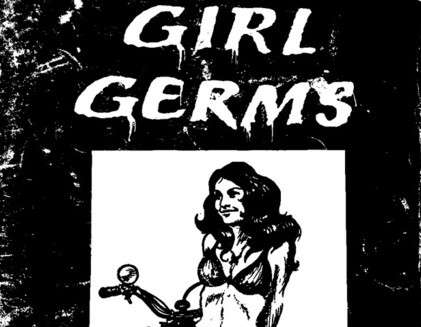

An early issue of Girl Germs, one of the zines archived in the Riot Grrrl Collection at NYU’s Fales Library, is made of ten sheets of standard-size office paper stacked on top of each other, folded lengthwise, and stapled twice down the spine. With the fold on the left, so the surface is taller than it is wide, the sheets become a half-size book of 38 pages and two covers. When the master copy was made in the early 1990s, its pages were hand-pasted with illustrations, essays, and letters either torn from notebooks or cut to size, then photocopied into a small print run by Molly Neuman and Allison Wolfe, who also played together in the band Bratmobile. Just inside the left margin of the essay that takes up all of page two — the corners of the pages are hand-numbered — a silhouette of rings from the spiral notebook that sat on the copy machine is clearly visible. The front cover is an illustration of a young woman wearing cutoffs and a bikini top, sitting backwards on a motorcycle; the back cover is a mailing label, with a return address of a P.O. Box in Olympia, Washington. The issue has no ads. The mailing address on the copy at Fales is blank, but penciled in the corner is “Prop. of J. Hopper,” of Minneapolis. The “J.” in “J. Hopper” stands for Jessica; the now-Chicago-based editor and music critic grew up in Minneapolis and photocopied zines for friends who, in those pre-internet days, had few other ways to read them. One of her copies made its way to Zan Gibbs, and then to Fales.

The issue had no publication date or issue number, either. “I think this is Girl Germs number four,” Neuman said while looking it over one afternoon this summer. It had been pulled from a folder titled “ɢɪʀʟ ɢᴇʀᴍs #1, 2 — ᴜɴᴅᴀᴛᴇᴅ.” “Number one has a whole hodgepodge cover on it.” She was seated at a table in a side room at Fales, opposite Johanna Fateman, a writer and former member of the band Le Tigre, and Lisa Darms, a senior archivist and the curator of the collection.

“Oh, really?” Darms asked, looking across the table, sounding a little alarmed. The archive is meticulously organized, especially considering that many of its items had arrived after spending the past two decades shuffling around when their owners moved to new apartments and new cities, or sitting in storage alongside other reminders of past lives. Before donating her four boxes, Fateman took them to New York, where she now lives, from Berkeley, and had moved them there from Portland, where she went to college; after spending her late teens and early twenties in what she’s called “the orbit” of the Riot Grrrl subculture, she’s only recently begun to feel like the label fits that period of her youth. “I had a real phase of feeling like I didn’t care, or like I hated this stuff, so I don’t think I cared for it that well,” she said. Darms, who now has come to think of Riot Grrrl as a moment as much as a movement, remembers some papers coming in with coffee stains.

“We’ll try to track down a number one,” Neuman said, with confidence. “Allison probably has one, I’m sure.” After a few minutes, she had already put Girl Germs back down and was scanning the rest of the tabletop, but Darms’ attention still lingered on the misnumbered issue.

“All right, I’ll correct this,” she said, looking down, then quickly outlined one of the archive’s central tensions. “That’s actually a perfect illustration of why it’s really hard to work with zines. There is something in this one that says ’91, so whoever dated it probably saw that, but I think it was copied from something earlier.” She raised her eyes. “And I think it’s also a sign of not thinking historically, right? Like, why would I put a date on my zine?”

“We didn’t know about publishing rules or practices,” Neuman said. “I mean, the first issue is volume one, issue one. And then that’s the last time there’s any — ”

“And it’s not just yours,” Darms said. “A lot of the zines are not dated. Because why would you? It’s about right now.”

“Yeah, exactly,” Fateman said. “The date is now.”

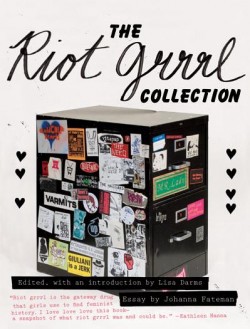

The Riot Girl Collection is available from Feminist Press and wherever books are sold.

The Riot Grrrl Collection received its first item in 2010: a two-drawer filing cabinet covered with stickers and filled with the notebooks, letters, and handmade zines donated by Kathleen Hanna, who played alongside Fateman in Le Tigre, and also in the band Bikini Kill. A photograph of this cabinet appears on the cover of a book of essays and selections from the archive, also called The Riot Grrrl Collection, that was published by The Feminist Press in June. Darms chose book excerpts from the first ten collections donated — there are now sixteen — and reached her deadline just before receiving a box of poetry, artwork, and writing collected by a teenage Sheila Heti, for a book whose first draft was eventually rejected because it was too controversial for its publisher, Random House.

The collection is focused particularly on the years between 1989 to 1996, which makes it one of the rare archives whose contents feel like they belong to both the present and the past. (Tavi Gevinson’s Rookie has a blog-savvy, digital-native, and largely female readership that’s familiar with zines — as is contributor J. Hopper! — and certainly each reader would have been making them, had she been born twenty years earlier; last year, though, just to be safe, the site began a story headlined “How to Make a Zine” by explaining what a zine was.) By circulating zines at shows, with friends, and in the mail, members of a movement that was geographically dispersed created a sense of community at a scale that was largely unavailable at a time before blogs.

The aesthetic they helped create — an empowered feminism that is brassy and outspoken while also confessional and intimate — suggests a latent influence on the style of contemporary blogging, as well as on novelists like Heti. Hanna recognizes zines’ similarity to blogging, but describes her time making them as more directly a way to share a personal, unsteady period of adolescence and find a way to her politics: “It was also about getting over your insecurities and not having to be professional and cross your T’s and dot your I’s totally perfectly. It was like, I’m just gonna write — whatever! It was very much kind of in keeping with the punk-rock sensibility, and in a way the arrogance of youth.”

Most of Fales’ other collections, like the papers of E.L. Doctorow and the personal library of Robert Frost, are more standard for a university archive, although NYU does have a reputation for acquisitions that challenge the idea of what qualifies as a historical object.

“The two forms of communication for Riot Grrrl ideas were bands and zines,” Darms said. By now, most of the bands have broken up.

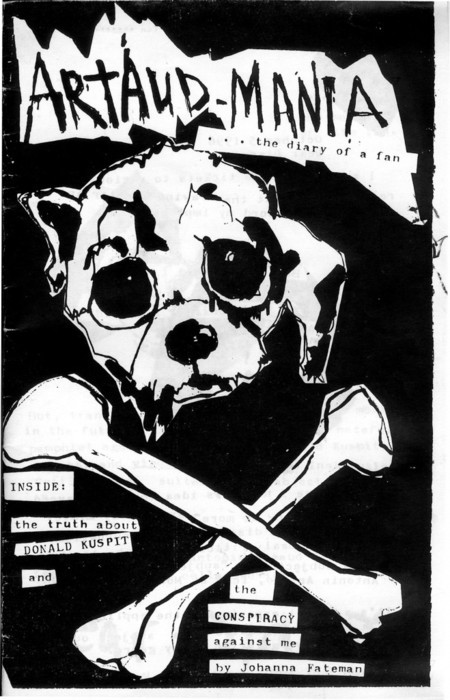

At a reading a few weeks prior to the meeting at Fales, Fateman spoke about Artaud-Mania, her fake diary of a real Artaud festival, and suggested that fandom, and the work of building a community, could be a vehicle for genuine cultural critique. About 150 seats had been set out for the audience, who nonetheless spilled over into the aisles. Although some of the reading’s attendees were old enough to have been at the concerts and shows in the 1990s, others more closely resembled what the audience might look like if there were to be a Bratmobile or Le Tigre show today. A young teacher at an independent school introduced herself by noting that she taught “the most patriarchal subject there is,” Latin. Another said she’d first come across Riot Grrrl through a course she’d recently taken in college, called The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager.

Darms, as an archivist, doesn’t see a tension between fandom and historical appreciation, and understands Riot Grrrl as a kind of avant-garde. “To me, nostalgia is a yearning,” she said recently, “and I think: How can we use that yearning and that longing in a positive way?” Partially that requires, for the authors of those zines, journals, and letters, an honesty about the things they wrote when they were teenagers, even if, when looking back, they sometimes feel ambivalence, or have had moments when their youthful pretentiousness made them want to cringe. Partially it requires an acceptance of those reactions, too. And, sometimes, establishing that kind of connection can work both ways. “It’s a model for other teenagers,” Darms said. “At the last panel, at Bluestockings, I was feeling a little nervous right beforehand, and then I looked back and I saw these three — to me they looked like about twelve- or thirteen-year-old girls, standing in the back. And I was like, Yesss! And I felt pretty great.”

Alex Carp is an editor for the McSweeney’s Voice of Witness book series and a reader at Guernica magazine.