Mobile Savagery: China Meets An Unprepared World

Mobile Savagery: China Meets An Unprepared World

by Abe Sauer

July 26th brought news items reporting two separate incidents of curious holiday gastronomy. First, tourists in the Paracel Islands posted pictures of a meal of Tridacna gigas — endangered giant clams. At the same time, vacationers in Greece snapped photos of themselves hoisting an extraordinarily rare “hexapus,” only the second ever recorded, just before killing it and frying it in a nearby pub. Yet only one of these stories was largely used as evidence to feed an expansive and growing set of opinions about an entire nationality and culture.

Of all China’s frighteningly fast advances, international travel is, in light of history, maybe its most stunning. Two decades ago, not only did most Chinese citizens have no means to get a passport, almost none had an inkling to want one. Today, state-run China Daily publishes photo galleries under the headline “一起去看世界十大奇观!” — “Together let’s see the ten wonders of the world.” Glossy, kilogram-heavy travel magazines, including — Condé Nast Traveler and Travel & Leisure — call out to passersby from China’s streetside magazine stands. Samsonite’s China sales grew by a fifth last year. After a half-century when the rest of the world did not encounter a single Chinese citizen on holiday, annual outbound Chinese travelers will soon number 100 million, if not this year, then likely the next.

And the world is having a hard time getting to know the Chinese.

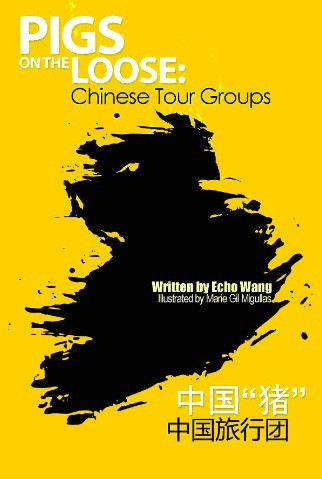

“Why is it women from other countries can enter and leave a toilet in such a way that you hardly know they are there, but with Chinese women the toilet takes on the atmosphere of a country market?”

That’s a question posed by Echo Wang in her new e-book, “Pigs on the Loose: Chinese Tour Groups.” The 92-page manifesto boasts chapter titles one would be excused from mistaking for some kind of adorable children’s series: “Pigs at Airports,” “Pigs on the Plane,” “Pigs in Restaurants,” “Pigs in Toilets,” “Pigs go Shopping,” “Pigs on the Move” and, simply, “Tour Groups.” The complaints range from the potentially legitimate — disregard for rules about smoking indoors — to the extraordinarily petty and seemingly universal — not leaving room for others to walk past while on escalators or “travelator” walkways.

Wang reserves special scorn, and a whole chapter, for “Pig Herders,” her term for the tour guides integral to many Chinese tour groups where few speak English. These guides’ importance has been noted, and nicknamed, before. In his wonderful 2011 report from a Chinese tour of Europe, the New Yorker’s China correspondent, Evan Osnos, called them “field marshals.”

In a long online discussion, Wang explained to me that she started writing the book in 2011 while translating children’s books for an Australian author. “When I discussed the problems I had encountered with Chinese tour groups during my travels he told me that it was no good complaining about it and that I should put my ideas in a book,” she told me. “I have tried to make it clear in the book that the term applies to the behaviors, not the Chinese people.”

“First Tour Group to USA from China” read the shirts of a group of about 250 that landed in Los Angeles on June 27. “Chinese tourists invade New York” read the New York Daily News headline a month later. This was the summer of 2008. That same summer, Hollywood greenlit a remake of 1984’s “Red Dawn,” with the Chinese as the modern-day invaders. (That movie, digitally altered to remove China and add North Korea, premiered in 2013, the same year Chinese travelers became the single largest per capita spending group in California.)

In 1983, the Chinese Government allowed the Chinese people to participate in organized journeys to Hong Kong to visit friends and relatives. Further relaxation in 1991 put Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand on the Chinese tourism map.

In 1997, China finally allowed outbound tourism. Until then, travel was restricted to business or foreign study, visas for either of which were legendarily difficult to obtain. (The plot of the recent number one Chinese film, American Dreams in China, turns on just such a 1990-era U.S. visa denial.) And though a trip to the U.S. or Europe was conceivably possible in 1997, in practical terms it was impossible for all but the few wildly rich or connected. But the dribble dribbled on. By 2000, Chinese were making 10 million overseas trips a year. In 2008, nations struck agreements with China to allow tour groups. By hanging responsibility for the return of all tourists back to operators, nations like America no longer had to fear handing over a tourist visa to a traveler who might not return to China. By 2012, outbound Chinese tourists numbered 83 million. By the end of 2013, that number could hit triple digits. In July, China’s travel agencies reported tours to Russia were up 120% over 2012, with many other European packages already sold out despite price increases of up to 20%.

Like Echo Wang, many who complain about Chinese tourists want to make it clear that they are complaining not about Chinese people as a whole. Yet the preponderance of reporting on Chinese tourism — when it’s not about bad behavior — is numbers, numbers, numbers. How much do they spend? (More per visitor than anyone else.) How many are there? (One hundred million and growing.) What’s the growth rate? In this, reporting on Chinese tourism falls into the same trap as a lot of reporting on China, just breathless measurements. As Evan Osnos poetically put it in his last New Yorker dispatch from Beijing, “The complexities of individual lives blunt the impulse to impose a neat logic on them… To impose order on the changes, we seek refuge, of a kind, in statistics.”

Absent a human element — absent individual life — statistics are neat and logical but also very, very threatening.

Ami Li wrote the South China Morning Post’s story on the Chinese tourists eating the endangered clams. Li, a former New York City crime reporter and Reuters editor, has the distinction of writing quite possibly the most popular news piece in modern SCMP history: “Why are Chinese tourists so rude? A few insights.” Since it was published on August 3, that post has remained in the top five most viewed stories on the newspaper’s website. It shows no signs of leaving.

When asked about her coverage of Chinese conduct, Li echoed a surface observation that has become the standard when discussing China’s great tourism boom. “I think the number of Chinese tourists has become so big now that they are so impossible to be ignored, and that’s a reason they‘ve become the centre of criticism,” she wrote in an email. (Wang to me: “The sheer numbers of Chinese traveling is going to put these people in the spotlight.”) Li says she does not know why the “Chinese acting badly” stories are perennially favorites at SCMP but the paper certainly finds them attractive. Maybe the apex of the form is SCMP’s August 5 headline “How North Korea is coping with uncouth tourists from China.”

Stories about Chinese tourists behaving badly like the SCMP’s are popular, in part, because they offer confirmation of long-held beliefs about China and its culture as well as — thanks to comments sections — a place to share these beliefs. The comment sections of most such stories are filled with anti-Chinese invective, first-person nightmares and venting about the perceived socioeconomic threat posed by China and the neat, logical accounting it represents. In her book, Wang makes a point to include a lot of these personal anecdotes. For more like them, simply search the term “Chinese tour group” at Tripadvisor.com, sit back and drink in anecdotes of globalization in action. Tourists complain about encounters everywhere from Yogyakarta, Indonesia to Manassas, Virginia to Annecy, France to Christchurch, New Zealand to Nairobi, Kenya, where one traveler “had the misfortune of being on a bus packed with a Chinese tour group who shreaked [sic] and shouted loudly every time we saw an elephant.”

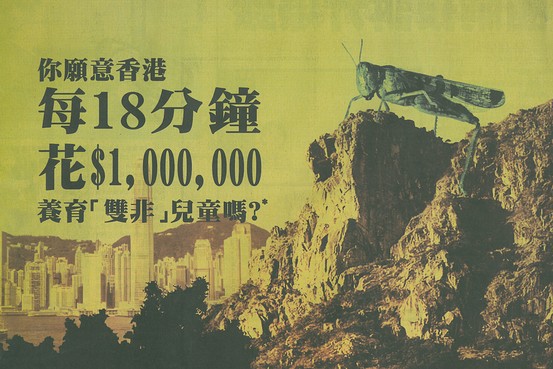

The popularity of SCMP’s pieces could be explained by the proximity of Mainland China to Hong Kong and the latter’s recent tension over a perception, shared by many, that it’s being overrun by the former. (A graphic 2012 newspaper ad warning of swarming “locusts” from the north did not help matters.)

But that does not explain why the same “conversation” is so popular a hemisphere away. Last month, writer Chris Bodenner penned a ditty at Andrew Sullivan’s The Dish titled “Why Do Chinese Tourists Have Such A Bad Rep?” It turned into not a one, not a two, not a three, not a four, but a seven update series over the month, packed with exactly the same kind of Tripadvisor venting. In the final post on the topic, Bodenner concludes that “the perceived rudeness of Chinese tourists is a symptom of the PRC’s rapid ascension as a wealthy nation — a nation that now has the disposable income to enable a middle class to join the global tourism market in droves.” The series, Bodenner adds with astounding temerity, is “in a way, is actually a tribute to China.”

The Dish’s intentions, like “Pigs” author Wang, may be a genuine attempt to start a conversation. But giving weight to the anecdotes of individuals, as historical precedents shows, generally turns any conversation about China or the Chinese into a stereotype echo chamber that probably only reinforces misunderstandings.

After a frank question about it, Wang said that spitting is her issue du jour. “A writer in the ‘Lonely Planet’ once wrote how much disease and flu would vanish if Chinese stop this habit,” she told me.

Spitting is a box to tick for China writers and reporters. At least two memoirs (“Pretty Woman Spitting: An American’s Travels in China” by Leanna Adams and “Too Busy to Spit” by Scott Kelly”) use spit in the title. It is easily the top complaint about Chinese society in the West and even within China itself, where Chinese who perceive themselves as cultured are almost harsher on the subject than foreigners. The elimination of spitting was a core target of the New Life Movement of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek (Soong Mei-ling), the Wellesleyan and Wesleyan-educated wife of the Generalissimo.(Echo Wang is herself a Chinese national.) When China’s Vice-Premier, Wang Yang, acknowledged some “uncivilized behavior” by Chinese tourists in a May statement, the inclusion of spitting felt almost required by CCP law.

It’s at the point in any spitting conversation that I usually point to the picture of Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon seated together, a spittoon front and center next to the Chairman’s right foot.

“Spittoon Era Comes to End” read a headline from the Lewiston Morning Tribune; the story noted that the brass “cuspidors” had been removed from the Idaho county courthouse. “Spittoons remain, however, in courthouse offices where they are standard equipment, and in the district courtroom.” The was June 17, 1951. The title of a June, 1967 Eugene-Register Guard column asked “How Do You Tell Children What Spittoons are For?” The Milwaukee Journal had a functioning spittoon in its newsroom until 1974, two years after the Nixon-Mao visit.

Last year, the Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens, Paris’ subway authority, felt forced to launch an expansive, zoology-themed public service campaign aimed at improving the civilité of residents. One of the messages was “don’t spit everywhere”; the representative animal was an inconsiderate pig.

Yet the Chinese as “spitters” persists, in part, because many do still spit, but even more so because it’s one of the only things people who have little experience with China know about the Chinese. That spitting is almost always mentioned in seemingly genuine, well-meaning discussions about Chinese culture — even by those who have no direct experience with Chinese culture and only know that the Chinese spit a lot from reading seemingly genuine, well-meaning discussions about Chinese culture — does not help matters.

A personal favorite, if imperfect, comparison is to global perception of the U.S. fashion trend of wearing pants so low one’s underwear (and sometimes more) hangs out. Acceptable? In many places but not everywhere.1

While realizing room for improvement, and as self-critical as anyone, many Chinese are perplexed by the global reaction. They wonder why respect has not followed their acquisition, and redistribution, of wealth. It’s possible that everyone involved in Europe’s tourism industry now owes a chunk of his or her livelihood to China. Chinese buyers are responsible for a quarter of all Burberry sales and, like many other luxury brands, the clothing manufacturer could be in the tank without the Chinese desire for its products. And yet, as a New York Times story from Singapore all the way back in 2005 was already griping about, Chinese tourists spend too much money in too wrong a way. This perception of wallets without personality or humanity leads inevitably to wrong conclusions. Germany’s National Tourist Board representatives recently referred to Chinese tourists as “our customers.” An offensive, if subtle, comment that demonstrates the view that the tourism goals of the Chinese are crassly commercial and not of the spiritual variety prized in the West.

Except, Chinese tourists are also far too cheap. Earlier this year, a Chinese whistleblower at a five-star resort in the Maldives revealed that it was hotel policy to remove the hot water kettles from the rooms of Chinese guests to prevent them from making instant noodles (and in turn forcing them into the resort’s restaurants). The Maldives resort industry — like numerous other sources, including The Dish’s series — also accuse the Chinese of not tipping. (One of the most common complaints about the Chinese is that, failing to realize that workers are often intentionally underpaid, they do not tip — a mind-bending complaint that should rationally say more about a broken economic system than the ignorance of a foreign culture.)

Thousands of miles away, in the European travel industry, it’s called “Sleep cheap. Travel Expensive.” And it, like the Chinese themselves, are increasingly loathed by a region that resents its growing reliance on the China tour Euro. Wang’s book, while not naming brand names, includes a few conversations with European hospitality providers who admit to an off-the-books policy of discriminating against Chinese tour groups.

These examples are more than believable thanks to some recent high-profile statements.

In 2011, luxury brand A.P.C. designer Jean Touitou told Hint Fashion Magazine that the Chinese were cultureless, and “the new fascists,” adding that “You go to China and want to kill yourself.” A year later, the head of fashion house Zadig & Voltaire said his new Paris boutique hotel “won’t be open to Chinese tourists.” In the ensuing outrage, Zadig apologized and clarified that he had only meant it would be closed to Chinese tourists arriving in “busloads.”

This kind of very real discrimination has created unhelpful tension and — maybe understandably — paranoia. In 2005, a Chinese tour group numbering nearly 300 staged a sit-in at Malaysia’s Genting casino to protest pig caricatures on the group’s meal tickets. The ticket illustration, explained management, was a way to differentiate pork eaters in the Muslim-dominated nation. Last winter, a Chinese passenger bumped off an overbooked United Airlines flight turned the slight into a major incident in China about discrimination. It’s a theme China’s media is growing hungrier to feed.

“We were troubled a little at dinner today by the conduct of an American, who talked very loudly and coarsely and laughed boisterously where all others were so quiet and well behaved,” wrote Mark Twain in his 1869 travelogue “Innocents Abroad.”

In an email conversation on Chinese tourist reputations, Evan Osnos specifically mentioned Twain’s commentary on Americans as “the original loud, imposing tour groups.” In 2011, Osnos wrote about the boom in Chinese tourism in the New Yorker piece, “The Grand Tour.” (Subhed: “Europe on fifteen hundred yuan a day.”) The Osnos story came just four months after a long Economist piece on the same subject: “A new Grand Tour.”

Both pieces largely focused on Europe, both noted the economics of Chinese tourism and included quirky color about Chinese preferences. What’s remarkable about Osnos’ dispatch is that it was from inside a tour that he had joined from China, while The Economist’s — published without a byline, per the magazine’s habit — was from a studied distance. The tones of the pieces could not be different. The Economist makes factual statements like “tourism is certainly not about discovering new food” and “excitement and acquisition are prized over pleasant, relaxing experiences”. Only at the end does the author get around to a passing statement about how Europeans used to act similarly, and ultimately concludes with a backhanded compliment about China’s “economic power.” Osnos’ grand tour ends on nearly the same topic — the morphing future of Chinese tourism toward solo travel — but it’s about a world in which China is a cooperative “we” instead of the persistent, if better traveled, “them.”

“I don’t think Chinese travelers are really any worse than we were at a comparable stage in our national story,” Osnos wrote me, adding that before Americans, Brits were “gawking at the Swiss, denouncing their espresso.” Osnos said: “There was a deep sense of curiosity and aspiration that ran through everything we did. Were we subtle and urbane? No. But I don’t think my American forebears were either.”

“It sounds like a banal observation, but it’s useful to remember just how close most of the Chinese population is to abject poverty and isolation: one generation or two, at the most,” Osnos said. “Beyond the occasional oaf, most of the travelers who get attention abroad are simply novices…. The ostensible sins of its travelers abroad are rarely acts of commission; usually, it’s just a lack of awareness, and the learning goes fast.”

A century ago, American writers were noting how it was westerners who, to the Chinese, exemplified barbarous manners. “Few of them even knew how to enter a room or to drink a cup of tea or receive a card correctly. Every act betrayed their uncouthness. Their manners were abominable….” wrote westerner Carl Crow in his 1940 memoir of a life lived in China, “Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom.”

Crow wasn’t the only one making the observation that the Chinese were impeccably mannered. A serialized story in the summer of 1900 — appearing sometimes under the headline “The Heathen Chinee at Home” — noted that “the Chinese gentleman prides himself upon his ceremonious etiquette and the punctual observance of polite formalities” before it went on to describe the practice of foot binding. The piece, published during the anti-imperialist Boxer Rebellion, was meant, like most pieces about China from America’s Imperial period in Asia, to dehumanize the Chinese.

In 1987, long after Crow was dead, I personally learned the concept of differing manners in China at the nation’s first-ever Kentucky Fried Chicken, just off Tiananmen Square. After waiting in line for hours, my eyes probably wild with homesickness, I ordered and sat, with my brother, to eat a bucket of the colonel’s secret recipe. Minutes later, I looked up to find the packed restaurant of Chinese, chopsticks and forks in suspended animation, watching in horror as my brother and I heartily tore apart legs and wings, smearing grease across our hands and cheeks in the process.

Much of the desire to change the international image of the Chinese traveler comes from the Chinese themselves. Wang’s book is an often crudely argued example. But is “Pigs on the Loose” more insulting than Harvard Business School MBA Sara Jane Ho’s Institute Sarita in Beijing? There, alongside Institute Sarita President Rebecca Li (“Li has two young children with her husband who is a member of the British aristocracy”), Ho teaches rich Chinese how to properly stir tea and pronounce “Louis Vuitton,” amongst other necessary behaviors. Tuition is $16,000 for the 12-day course. It’s enough to make a guy want to see someone spit a little bit.

“The people at the top of Chinese society look down on people below them,” said Wang about Institute Sarita, dismissing it as “a money maker for the people involved.” Wang would rather see “free courses on cultural awareness being funded and run at the level that makes them available for all the Chinese that sign up for a group tours.” She thinks that compulsory attendance could even be a prerequisite for receiving a passport. Wang tells me that when she completes her MBA, she hopes to produce a public service video about tourist behavior. But she says she wants it to be humorous. “I see it as being in the Fawlty Towers, Monty Python and Benny Hill style of comedy,” she said. She imagines the setup: “Opening shot is Chinese guy pissing on wall of famous building. He get kicked in the bum by very large aggressive westerner. Westerner points at the sign that says ‘public toilet.’ Policeman arrives. Handcuffs Chinese and takes him away. Maybe court scene with final shot being jail or fine.”

I suggested it might be historically insensitive or at least counterproductive to show a western foreigner smacking around a Chinese person in a video that’s meant to be engaging and instructive. Wei agreed. “Yes, you might have a point. Maybe it’s a Chinese guy who kicks the urinating guy… and the policeman is a foreigner. Maybe Indian or African or European.”

“Oddly enough, I actually think that today’s China and the United States have more cultural DNA that unites them than divides them,” Osnos told me. “Enormous countries that see themselves as the center of the world, a culture of striving, the superpower complex.” Osnos’ comment reminded me of the closing scene from an episode of “Mad Men”; after a relaxing picnic, Don Draper and family pack back into the sedan, an afternoon’s worth of litter and garbage left in the bucolic countryside without a second thought. I’m not sure about others, but my immediate reaction to that scene was to think of China.

Noble savagery becomes simple savagery when the graceful spirituality of immobilizing poverty is replaced by middle-class incomes and Levi’s. And there is no loathing quite like self-loathing, which is what we really see when we look at the Chinese.

In the end, whether Chinese people are out $16,000 at the Institute Sarita or $1.99 at Amazon.com, the bad news is that improved behavior is itself never going to win the Chinese acceptance overseas. The cultural clash with China’s tourists is really the latest version of a much larger, ongoing clash of misunderstanding between East Asia and the west. A generation ago, the Japanese were criticized roundly, despite a reputation for faultless manners. (Ironically, the extent of Japanese manners became a source of criticism and jest.) That is, until the Japanese ceased to be an economic threat.

But Osnos sees hope in at least the China-U.S. relationship. “It’s interesting to compare it to the relationship between America and its stalwart allies — say, Saudi Arabia, which has been a close ally for decades,” he said. “How many Americans talk eagerly of studying Arabic and settling down in Riyadh?”

I want to agree with Osnos but cannot shake the heft of history. A November 23, 1938 AP story, about a party at the University of Michigan President Alexander Grant Ruthven’s house, reported that a young Chinese student who had studied a book of etiquette in desperate hope of fitting in, said in response to being handed some tea, “Thank you sir or Madame as the case may be.” In response, the guests all laughed at the young man.

1 Too much its own topic to go into length but worth noting is that perceptions of China in the West are not only poorly served by an obsession with big numbers but also how the only China stories ever relayed by popular blogs are of fantastic, grotesque or tragic Chinese incidents of birth defects, murder, backwardness or other misfortune. Sadly, even a few of the most popular blogs from China seem nearly completely and obsessively focused on painting Chinese people in the worst possible light.

A note: There are few early American reports about Chinese tourists largely because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, signed in 1882, strengthened in 1924, and finally weakened in 1943 with a statement from the U.S. Senate that the act was “not born of ill will toward the Chinese” but instead was “exclusively economic.” The act was not fully repealed until 1965, a decade and a half into the People’s Republic’s half-century of restricted travel. The act itself addressed the illegality of Chinese immigration and naturalization but also made leisure trips to America prohibitive. As a result of the Chinese-only act, even Chinese of great financial means faced huge difficulties going to America. Congress officially approved an apology for the act in 2012. It’s worth noting that Canada also had restrictions on Chinese immigrants and visitors.

Abe Sauer is the author of How to be: NORTH DAKOTA. He is currently working on a book about Chinese consumers.