Occupy Boston: The Glory And Imperfection Of Democracy

by Tyler Wells Lynch

It was three hours into Friday night’s General Assembly meeting at Occupy Boston. One hundred or so protesters were seated on a grassy knoll in Dewey Square, well within the forbidding shadow of the city’s 32-story Federal Reserve Bank. The night had started cool but clear — grazing 50 degrees with a few stars dotting the twilight sky — but the temperature had gotten noticeably colder. I could see my breath, and the financial district’s rush-hour hubbub had long since passed. For the past three hours the crowd had been debating the creation of a new working group called Urban Youth. The process was laborious: While the facilitator had a microphone, it didn’t carry far, and each comment had to be repeated through Occupy’s elaborate Human Microphone system. The process was reminiscent of New England bureaucracy and legislative officialdom, procedures I’ve often panned as a local. Things were said like: “We need to see everyone’s hands in the air, because if we don’t have a quorum of people voting it won’t be considered consensus.”

At one point it looked like a decision was about to be reached. After hours of legislative meandering, the facilitator’s excitement was palpable. “Are there any points of information? No points of information. How about strong objections? I’m not seeing any strong objections. Are there any friendly amendments?” There was a long pause. An individual raised his hand, which indicated an amendment proposal. A moan rumbled through the crowd. The facilitator chuckled. “This is democracy,” he said. “Everyone has a voice.” The crowd began to cheer. “This is why we do this. Because we all have a voice!” You could feel the sense of frustration, of fatigue giving way to elation. I thought: Perhaps the essence of democracy is somehow entwined with the procedural humdrum of a Cambridge zoning board.

But then, late last night, the police made a sweep through one of the Occupy Boston encampments, making somewhere between 50 and 100 arrests. A bit of business, which, as far as I know, has never happened to a Cambridge zoning board.

Over the last week, I’ve made several trips to the Occupy Boston camp, including an extended visit last Friday. “My initial reaction is that Boston is better organized,” said Laura, a young woman who had just arrived from the New York protest. But, she noted, there were fewer people here too. The taxonomical classification of the protest’’s many “working groups” is an example of this organization; each “department” is devoted to a specific cause, a la the proposed Urban Youth collective being debated Friday, and each is responsible for its own maintenance. They include, among others: media, direct action, logistics, medical, legal, arts and culture, spirituality and a Queer Caucus. All group proposals are subjected to a stringent democratic process before approval.

“Also, in New York, there are no tents,” she noted. Here in Boston there were at least 60 tents housing some 200 people on any given night, but those figures have been growing since occupation began on September 30. For legal purposes, protesters can thank the fact that Dewey Square is owned by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, who have also allowed occupiers to siphon electricity from an adjacent maintenance building and give power to the media tent and PA system.

On Monday, a second encampment went up at a nearby park along the Rose Kennedy Greenway. This second camp was the focus of Tuesday morning’s police sweep, although reports are emerging that the protestors had permission to camp there.

The arrests and treatment of the protestors mark a strong shift in the Boston Police Department’s approach to the protestors. Up until last night the relationship might have been described as cordial, with no arrests and a seemingly shared interest in keeping the peace. Indeed, at a rally in front of the Boston Fed last Friday, a demonstrator with a bullhorn called for a thanks to the Boston Police Department, members of whom were standing in a neon-outfitted phalanx at the bank’s entrance. The request was met with fervent applause. “Because you’re one of us!” shouted a young man in a bandanna, pointing squarely at the stoic police officers. I detected a few grins among the cops. Later, when I spoke to a few of them, BPD officers told me they had respect and were even in agreement with a few of the protesters’ grievances.

Around Occupy Boston, the phrase “I can’t speak for anyone else” is something of a prelude to conversation, like saying thank you or shaking someone’s hand. It’s symptomatic of the movement’s staunch commitment to diversity. Before the General Assembly started, I had a conversation with a Marxist who seemed to be pitching outright revolution, then listened to a soapbox speech from a man touting anarcho-capitalism. Later in the night I spoke to a crew of Ron Paul supporters, while another group told me about their attempts to further include libertarianism in the discussion. Of course, this parade of ideas is not without consequence, and you could discern a bit of a cold war among the different parties. One Ron Paul supporter told me he felt he’d been “eighty-sixed” from Occupy Boston. I overheard another conversation between a couple of anarchist punks complaining about how much the libertarians were speaking during the General Assemblies. This was right before a drunk girl screamed “Get off welfare!” from a passing party bus.

The Occupy Movement has been much criticized for espousing varied or inconsistent objectives, even by sympathetic observers. (Fox News contributor Dan Gainor’s criticism that the movement has “no stated goals, no public spokespeople and many of the most ridiculous attendees you could imagine” is typical. But hark: This bigness, this fluidity, this multiplicity is the point.

During an open-mic session at the end of the night, a 20-something construction worker with a vowel-rich Boston accent took the knoll and praised Occupy’s reluctance to commit to any one ideology.

“Numerous people have said to me that the best thing about this whole thing is that we haven’t released any statement yet, so people don’t know what the fuck is going on,” he said, to great fanfare. “They have to come down here and talk to individuals and meet us face to face!”

At Friday’s General Assembly, everyone seemed to understand this, even as they bickered over the use of the term “prioritize.” The point in question was a statement to be published by Urban Youth and ratified by Occupy Boston. Some members disliked the idea of prioritizing one segment of the 99 Percent over another. Others viewed it as the natural state of things. Indeed this exchange sent a chill of silence through the crowd:

“Mic check.”

“Mic check!”

“I would like to propose.”

“I would like to propose!”

“That specifically naming.”

“That specifically naming!”

“Any group.”

“Any group!”

“Will introduce.”

“Will introduce!”

“Classes.”

“Classes…”

A mild sigh echoed through the crowd with that last word. A few more friendly amendments offered similar points with lukewarm enthusiasm. Then a mic check from behind me, with the observation that “I am hearing from amendments … a lack of undertanding … of the realities of race, class, gender!”

The person continued: “And the reality that the ninety-nine percent IS divided!”

This set off a large applause, which is unusual given protesters’ insistence that clapping is noise pollution and makes things difficult to hear, a reason for the development of the intricate system of hand gestures used to indicate votes and questions and comments.

“My friendly amendment is.”

“My friendly amendment is!”

“Even stronger language.”

“Even stronger language!”

“Recognizing the realities.”

“Recognizing the realities!”

“That the ninety-nine percent includes.”

“That the ninety-nine percent includes!”

“People with privilege.”

“People with privilege!”

“People who experience oppression.”

“People who experience oppression!”

“In varying and different amounts.”

“In varying and different amounts!”

Occupy Boston’s recently endorsed Statement of Diversity of Tactics articulates this thinking:

Our solidarity will be based on respect for diversity of tactics and plans of other groups. As individuals and groups we are committed to treating each other as allies in the struggle. The actions and tactics used will be organized to maintain a separation of time or space to protect the autonomy and safety of the movement.

We realize that our detractors will work to divide us by inflaming and magnifying our tactical, strategic, personal and political disagreements. Therefore, any debates or criticisms must stay inside the movement to avoid any public or media denunciations of fellow activists or events.

Despite the array of concerns among the protesters, few of them seemed as passionate or angry as Jason, an Iraq veteran who now works as a roofer in Jamaica Plain. Later, he would tell me he comes from a family with a long tradition of military service; despite his own service, he has had trouble paying medical bills in recent years. He took the knoll at the end of the night, when the finicky P.A. was put up for open mic. His hands quivered as he read from a scribbled piece of notebook paper, eyes fixed permanently downward with his voice bouncing off the skyscrapers framing Dewey Square. He wore a sweatshirt that read “Iraq Veterans Against the War.”

“I don’t care if you wear a fucking suit to work, or if you own a fucking yacht or if you own a successful small business — you’re one of us! Or even if you’re a banker. Yeah, they can afford better vacations, nicer cars and a better education for their kids, but can they snap their fingers and influence foreign and domestic policy?

“I don’t care if it’s ninety-nine, ninety-eight, ninety-seven-point-fucking-six percent — I don’t give a shit. Republican, Democrat, Independent, Socialist, Libertarian, redneck, hippie, college student, union worker, banker, baker, lawyer, police officer, firefighter, teacher, stripper, fireman, farmer, preacher: Come one, come all! Join in Operation American Freedom!”

Later, Jason would tell me that his use of “Operation American Freedom,” besides a jab at the Iraq War’s tactical name, was also recognition of a resolution, proffered by a previous speaker and since adopted. Titled “Memorandum of Solidarity with Indigenous Peoples,” the resolution committed the group to “Decoloniz[ing] Boston with the guidance and participation of First Nations Peoples.”

Whatever Occupy Boston chooses to call itself, the group is characterized by its commitment to organized democracy. Consider how they make a decision: All proposals and subsequent amendments are subjected to an inventory of democratic motions that include clarifying questions, points of information, strong oppositions and friendly amendments — in that order. Then, the process is recycled, in its entirety, until no comments or objections remain. After that, the facilitators check for blocking procedures, then move to consensus, take a vote, which must carry 75 percent approval (votes are recorded via hand gestures called “temperature checks”), and only then can the group claim they’ve reached a collective and democratically obtained decision.

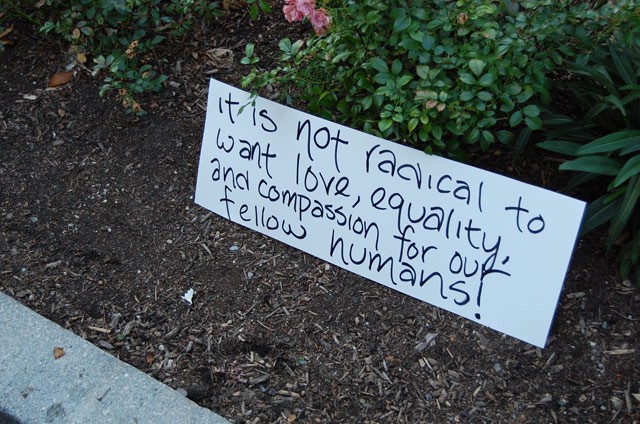

At different points on Friday I found myself wondering, Why this structure? Why such inflated policy? But over the course of the grueling three-hour meeting, I realized that this is democracy — in all its glory and imperfection. In watching these operational flubs mixed with youthful vigor and determination, I was reminded of a certain Winston Churchill quote: “No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government, except all those other forms that have been tried.” The process is long and frustrating and sometimes inflammatory, but the jubilation of a group decision is infectious, and you can’t help but feel part of democracy in its rawest form. Yes, it’s messy and bureaucratic and sometimes inefficient, but this is the point: Everyone has a voice.

It’ll be interesting to see how much longer those voices will be allowed to be heard in Dewey Square. Yesterday Mayor Thomas Menino told the Herald that “[t]here will be a time when they’ll have to leave that location.”

Tyler Wells Lynch is a young writer living in Boston. His work has appeared at McSweeney’s, Nerve and a number of blogs throughout the innerwebs. He has red hair, if you see him.