I Blew a Kiss to the Cherry

On the Philosophical Biology of Marietta Pallis (1882–1963).

I came across Marietta Pallis because I’ve been researching a medievalist called Hope Emily Allen. In the 1930s, Allen identified an important medieval text written by a woman named Margery Kempe; I’ve long wanted to write a book about that discovery. For a time, Marietta and Hope lived together at 116 Cheyne Row, an extremely nice house right on the bank of the River Thames, in Chelsea. The historian Joan Wake (who called Pallis an “erratic genius”) lived nearby on Cheyne Walk, and there was a boarding house for women students down the street. It was a colony of a sort, a little enclave of woman thinkers. I went to stand on their street corner in August, but I couldn’t hear them whispering on the winds of time or anything.

Pallis wrote a poem to Allen, and it went like this:

I blew a kiss to the cherry

and the wind blew its petals to me:

with its delicate flakes I was whitened,

I loved, and the month was May.

Here, Pallis uses a sort of lyrical invocation common in medieval literature, launching into her theme through the language of flowers and springtime. It seems written so specifically for Allen, the talented medievalist. Lovingly designed, perhaps.

Scholars cite this poem when they want to back up the popular theory that Allen was queer, since just observing that she never married a man doesn’t seem quite sufficient. It’s not an outlandish theory, and it’s not an inappropriate piece of evidence. (Although it would be a good historical prank to be a gay poet and write a love letter to your straight friend.)

The book I want to write is a double biography of Allen and Kempe, but it relies on a historical triangle drawn between those two women and myself. If the line in that triangle which links me to Hope could include a common sexuality, all the better. My own advisor, godmother of queer medieval studies, has already written a little about her in these terms. The topic is good, and the field is ready. But if I’m serious about this book and I want to make Hope’s queerness a theme, I thought, I should probably be sure.

So, I went after Marietta Pallis. I read her poem like a piece of forensic evidence, hoping to find some kind of lesbian fingerprint that would crack the case wide open. But the “case,” as so often happens, turned out to be bigger than I expected. The deeper I went into Pallis’s life, the more her mystery expanded.

Alongside a woman named Phillis Clark (née Phillis Ursula Riddle, separated wife of Andrew Clark, often misspelled “Phyllis”), Pallis is buried on the central island of the Double Headed Eagle Pool (pictured above.)

The pool is in the shape of Greek Orthodox crosses, an Imperial Crown, Pallis’ own initials, and a double-headed eagle; it can only be seen from the air. Pallis had it dug in 1953 on the land she owned at Long Gores, Hickling on the Norfolk Broads for the five hundredth anniversary of the fall of Byzantium. She designed the pool herself, and had it cut from the peat using traditional Norfolk techniques. Pallis loved to swim and often swam naked in her pool — a practice described by the Journal of Historical Geography as a “gentle private bohemianism.” She died in 1963, at the age of 80, whereupon she took up permanent residence in the earth at its middle.

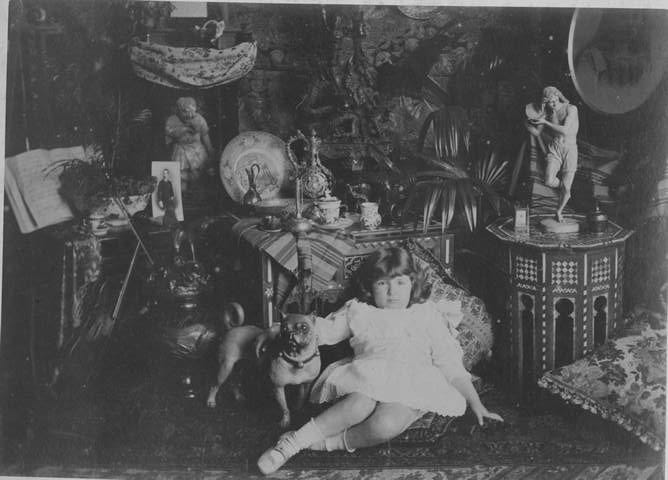

Pallis was born in 1882, in Bombay. Her father was a Greek poet named Alexandros, who caused riots in 1901 Athens by translating the New Testament into Modern Greek (eight people died; the translation only became legal in Greece in 1924). Her mother was named Julia Ralli. They moved to England in 1892, settling in 1894 in Liverpool. Pallis grew up loving landscapes, and she became a talented ecologist, a botanical painter, and a woman who wrote romantic poems to other women.

Pallis studied at the University of Liverpool, where she investigated the Dee estuary flora, and then worked on natural sciences at Newnham College, Cambridge. In 1911, she published two articles in esteemed scholarly journals: ‘Salinity in the Norfolk broads,’ and ‘The river-valleys of east Norfolk: their aquatic and fen formations.’

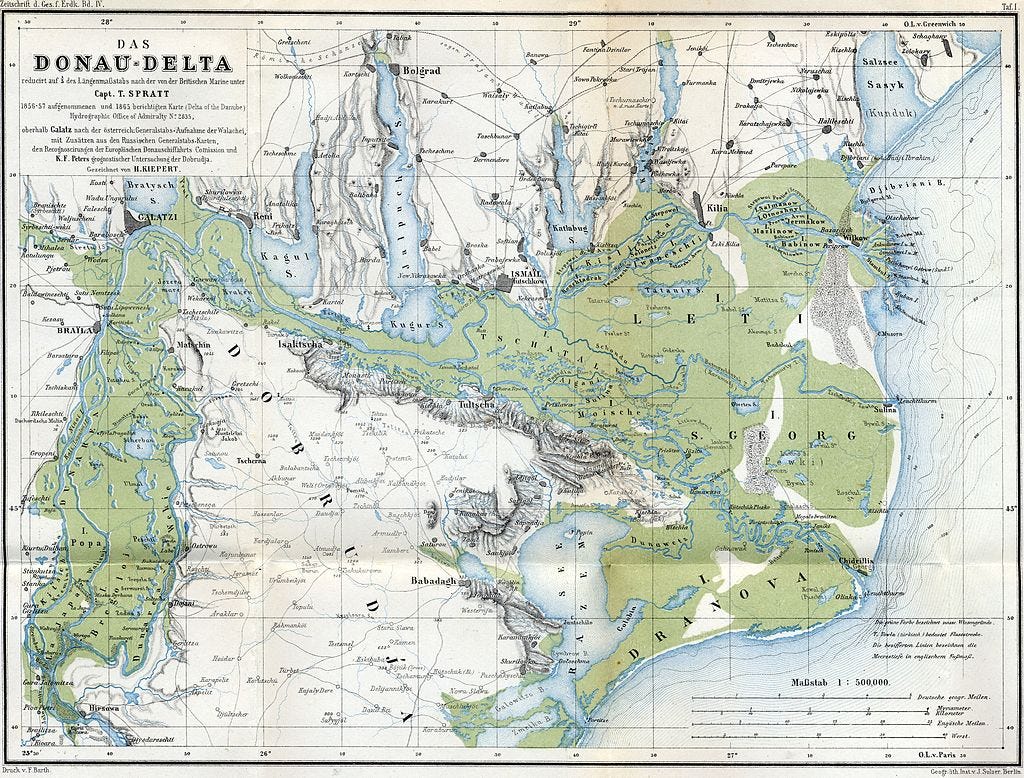

Pallis traveled to the Danube delta in 1912–13 to research a type of plant called plav. Her paper on plav was published in the Journal of the Linnaean Society: Botany (July 1916), titled ‘The structure and history of plav: the floating fen of the delta of the Danube.’ Pallis became interested in philosophical biology, exploring vitalism — the theory that there is some indescribable life-force animating all species.

A history of Norfolk peat-digging records that Pallis was a serious enough botanist to have had a couple of plants named after her: “a variety of Dog Violet, local to the dunes between Waxham and Sea Palling, was once known as Miss Pallis’s violet.” A hairy-leafed ash species that Pallis collected in the Danube is named for her, too: the Fraxinus Pallisiae. One of these trees is planted at her grave.

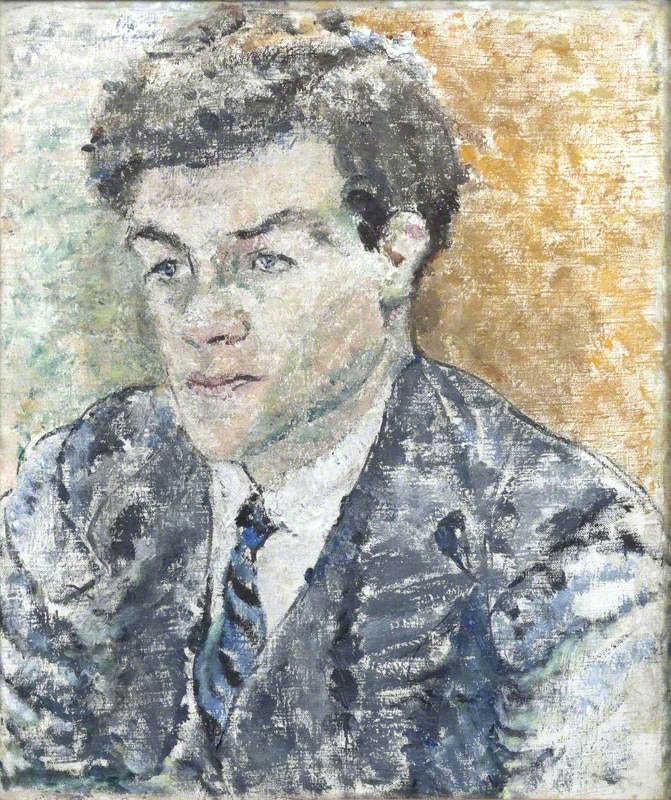

Pallis was a scientist, but she led an artistic life. She veered into cultural history, writing a book called Tableaux in Greek History (1952) condemning modernity and celebrating Orthodox Christian Byzantium. The Dictionary of National Biography notes that her “theocratic maverick conservative social philosophy was expressed through a bizarrely alliterative prose.” Pallis also took up painting alongside her botany studies. She had a solo show in 1938 at the Bloomsbury Gallery, but she never became a success. Her paintings are rather nice, in a squishy post-Impressionist way.

I fell into Pallis’s life like a swimmer. I came across a trove of photographs on the internet, and wrote to the email address on the webpage. I got in touch with Caroline Shelton, Pallis’s grandniece and goddaughter. In Bobst Library, there was a copy of a book called Sacred Gardens and Landscapes: Ritual and Agency. It was full of photographs of Pallis, as well as a painting she made of Allen that I’d no idea existed.

But by now, Allen had drifted toward the back of my mind. The motivating energy driving my research into Pallis had been my desire to know whether or not she had a romantic relationship with Allen. I knew that Pallis was buried with a woman, and this seemed, by parallel, to legitimize my speculation.

But that speculation had come to feel corrosive. It reduced Pallis to a clumsy cipher for queerness poised around the edge of another woman’s life, a life which I in turn wanted to bend to fit certain specifications. And all I was going on was one poem. Is that enough to turn a woman into a symbol?

Pallis’s goddaughter Caroline told me that she and her siblings think “partner” is too specific a word for Phillis. “Friend in middle and later life,” she thought better. Another relation, Dominic Vlasto, agreed, saying,“As far as I know, neither Phillis nor Hope was ever Marietta’s ‘partner’ in the sense people assume today.”

The happy couple buried in the marsh is too simple a vision. The past never quite matches the story that drew it to you in the first place, and historians can be clumsy. Past versions of society have shielded the sexuality of the dead from our gaze, and that is that.

Pallis broke away from Allen and Kempe in the queer constellation I had tentatively assembled. She became her own planet. And as soon as I began to try to see her for who she was, not what she was, I stopped.

Pallis and Allen have become imaginary companions to me, but they were real people, women who lived just beyond the horizon of our time. Writing about them and using the word queer is an act of reclamation, and it is an assertion of the value of queerness in the face of big silences. But the silence I have been trying to shatter is the loneliness of subjectivity in time — a loneliness I wanted to lessen by conjuring them up as friends and allies in the lifelong work of being academics.

There is exactly one book about Pallis, by W. T. Stearn. I am not going to write another. Maybe I am not going to write any books at all. Stearn notes that “Neither Greece nor Britain noted the passing of this colourful strongly individualistic forceful woman.” After Pallis died, her pool became overgrown. It was cleared again in the early eighties, though, and now anybody flying over Norfolk can catch a glimpse of this piece of art, the resting place of Marietta Pallis and Phillis Clark.

You can see films of sailing boats, farming, and a livestock market made by Pallis via the East Anglian Film Archive.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic.