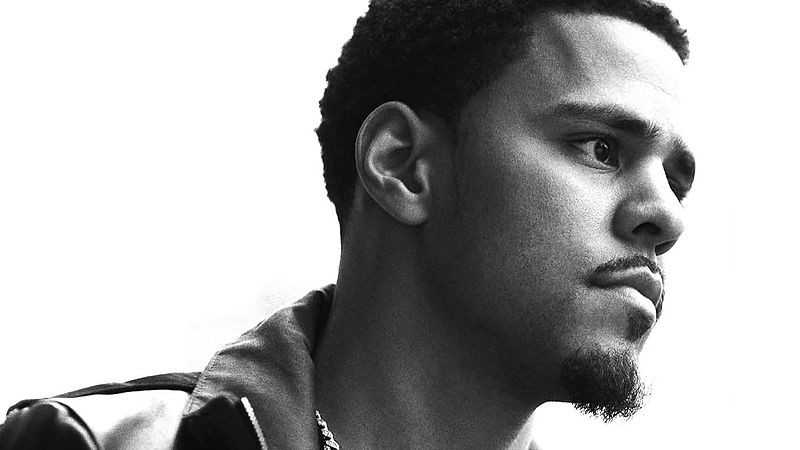

J. Cole's Authentic Inauthenticity

When kitsch thinks it’s rich

Last month, North Carolina rapper J. Cole released his fourth album 4 Your Eyez Only. The reviews were notable less for their praise than for their cagey, sheepishly qualifying disclaimers. “In one of hip-hop’s most populist periods, he is a divider — a loyalist to out-of-fashion values and a conscientious objector to dominant trends,” wrote The New York Times’s Jon Caramanica. “Snowblind loyal subscribers will flock to crown Cole as a generational superhero,” wrote Jesse Fairfax on HipHopDX, “While lazy detractors won’t soon be swayed from steadfast views that he’s human Hip Hop Nyquil.”

At Vulture, Craig Jenkins identified Cole’s latest music as “proof he buys into the defender of the faith business as much as his listeners do, but neither party seems to understand that rap flourishes better without strict rules and boundaries.” The headline of Paul A. Thompson’s Pitchfork review read, “On J. Cole’s fourth album, he wrestles with the fragility of life and the importance of family ties. He also sands down some of his worst impulses.” Hardly glowing recommendations for one of rap’s most visible stars, the auteur who, to quote hip hop’s most enduring meme, infamously went platinum with no features.

“J. Cole Went Platinum With No Features” Is the Best Meme Right Now

For the last half decade, J. Cole has enticed and confounded listeners, inspiring vocal partisans on both sides. The dispute is predicated less on the question of whether or not J. Cole is good — some of our most essential rappers are not good by quantifiable metrics of technique, creativity and charisma the keys to their triumphs, and what is good anyway? — than on whether or not he is the type of good he so passionately purports to be. That is: an emblem of ambitious sophistication upholding the tradition of rap’s venerated lyrical maestros.

J. Cole maintains a scholar’s appreciation of the high-church hip hop of his youth. As a middle American child of the Reagan presidency, his primary influences are Nas, Jay-Z, and 2Pac. He treats the most literary rap of the mid-1990s with a religious zeal, and is in many senses an adept mimic of his idols. A fallacious reading would be that because he sounds like Nas and Jay-Z, who are good, then J. Cole is also good. The flaw in this logic is that Nas and Jay-Z were imperfect human artists, and J. Cole has been most successful in cribbing their least meritorious elements.

Even as an adult Nas personified the precocious innocent, compiling dispatches from his broken world — a projects Peter Pan with a notebook. Rather than his omniscient Hemingway-esque detail and the capacity to squeeze life from his characters’ little tics, J. Cole aped his ham-handed concept songs. In attempting to replicate Jay-Z’s impenetrable bombast, Cole fatally overlooked its predication on the narrative understanding that Jay-Z was a drug dealer before he was a rapper (the second of multiple hustles he’d go on to master). For J. Cole, rap has always been the be-all and end-all, success and fame pursued for their own sakes in a circular ambition that would have doomed his heroes.

Cole’s apologists cite his reverence for the craft, but even as a dutiful student, he managed to whiff on many of the critical details. The condensed J. Cole origin story is that he moved to New York and stalked Jay-Z until he was offered a record deal, a weird perversion of Jay-Z’s own rags-to-riches tale. For Jay-Z, rap offered a chance to turn legit. His appeal lay not in his posturing but in the skills and priors which legitimized it, an Alger narrative which Cole misinterprets. Jay-Z’s gusto is an effect, not a cause, of his greatness. J. Cole is what Jay-Z might sound like if he’d spent his adolescence listening to his own records instead of living them.

If this supplies ammo for critics who label Cole boring or corny, his delusions of grandeur are further undermined by the everyman persona he inhabits. He is, by his own accounts, something of a regular guy with a regular life, which, when expedient, would make him a refreshing alternative to his most grandiose peers. Yet the melodrama and braggadocio with which he laces his first-person accounts are not only out of scale, they stand in direct opposition to a character which demands humility and self-deprecation.

Cole is, too frequently, a walking, rapping paradox. His 2014 single, “No Role Modelz,” a five-minute slut-shaming screed, opens with the “Fresh Prince”-invoking clunker, “Rest in peace Uncle Phil, for real, you the only father that I ever knew / I get my bitch pregnant, I’ma be a better you.” He raps of the late pop star, “My only regret, could never take Aaliyah home / Now all I’m left with is hoes up in Greystone.” When convenient he is an advocate of tolerance, but he deploys pejoratives “retard,” “bitch,” and “faggot” as naturally as other rappers do ad libs, which wouldn’t be so notable or deplorable in itself if not for the fact that hardly any rapper is as self-righteously moralizing as Cole is. “She shallow but the pussy deep,” indeed.

Even when not toeing the line of political correctness his dearth of self-awareness manifests itself in bewilderingly tone-deaf moments. “Wet Dreamz,” another 2015 single, is a guileless account of losing his virginity. On paper it promises to be a self-effacing subversion of machismo, but the performance is so bereft of humor it borders on sociopathic: “You know that feeling when you know you finna bone for the first time / I’m hoping that she won’t notice it’s my first time.”

Cole aspires to ambitious distinction, all but shouting it from a mountaintop, but rarely delivers. He sounds passionate when his words are vapid. His love songs are too ravenous to seem heartfelt. A 2013 song was structured as an open apology to Nas for recording a derivative pop song which the legend evidently found repugnant. Cole’s punchlines are appallingly dreadful and discomfitingly reliant upon fecal references. His worst offenses are so egregious that they all but disqualify his music from consideration.

There is a running back who was born the same year as J. Cole named Shonn Greene who spent most of his professional career with the New York Jets. Greene weighed 230 pounds and was a unanimous All-American at the University of Iowa. He didn’t attempt to run around defenders so much as run through them. This often made him exciting to watch, because he might as easily truck-stick a hapless defender, or at least drag him a few yards, as get stuffed at the line of scrimmage. The problem once he reached the professional ranks was that NFL defenders are really good at tackling, and Greene didn’t improvise well, usually running in the direction the play was drawn even when his blockers blew their assignments. For Jets fans, it eventually became infuriating that a player as talented as Greene couldn’t or wouldn’t do something as elementary as attempting to run around people trying to tackle him. Shonn Greene was strong, fast, powerful, and fearless — all traits, if not base qualifications, of good running backs — but he wasn’t a good running back.

I don’t mean to distill this to J. Cole Equals Shonn Greene, but both had many of the necessary credentials (upon receiving his one-page resume, the HR department is very excited about J. Cole), really good intentions, and really bad instincts. Cole aspires to rap’s most traditional high-art variants. Punchline rap, usually structured in rhymed couplets with a conventional comedic setup followed by a play on words in the latter bar, is a time-honored craft which has produced some of the most entertaining components of the New York hip-hop canon. Autobiographical and narrative rap are laudable endeavors which often produce gripping, revealing music. But Cole’s ambition is not sufficient in itself, and he is usually a punchline rapper with terrible punchlines, a memoirist with no self-awareness, and a storyteller without subtlety.

This rationale applies to most any job or medium. Mechanics and aspirations do not a great writer make. Nor is sophistication restricted to the sort of hyper-articulate rap J. Cole favors, which when affected poorly plays like nails on a chalkboard. Juvenile, Too Short, Suga Free, and E-40, for example, are timeless, iconic rappers for their artistic explorations of decidedly un-lofty subject matter, all the more so because they recognized the function of rap as entertainment. A middling writer of literary fiction or a mediocre arthouse auteur is not superior to an elite YA novelist or a director of great slasher films. Cole is an above-average technician with such disproportionate megalomania that, as a commercial artist, it offsets his strengths.

In a parallel universe very much like ours J. Cole is very good, and it’s only after you spend some time there that you begin to see the seams of this Bizarro World. J. Cole might be a savant for his successful shrouding of populism as sophistication. He blends so many elements of beloved rap acts that a passive listener might confuse them. He fuses the simulated artifices of his childhood favorites with Kendrick Lamar’s cinematic scope. His punchline setups and obsession with fame are reminiscent of Big Sean. His lusty ballads, more longing than loving, bear resemblance to Drake’s.

This conflation is, of course, brilliantly deceptive. “Life Is a Highway” sounds like a Springsteen song to the point where its structural and aesthetic similarities almost mask that it’s a four-and-a-half minute discourse on a single senseless aphorism, containing none of the poetry or poignance that separates Springsteen from a Canadian impostor. As a storyteller, Cole’s oft-cited analogue Kendrick is a master of nuance, a self-conscious spectator forever trying to skirt the destructive impulses endemic to his native Compton. Cole lacks Kendrick’s shattering empathy, his signature, unshakeable bafflement that children grow up to be shitty adults. Next to Big Sean, a cockeyed clown prince, Cole’s eager-to-please goofiness is conspicuously absent, and his ballads are as self-pitying as Drake’s, sans the Torontonian’s mercurial showmanship. Even Wal-Mart sells clothes that look like designer brands.

Carl Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, a 2007 entry in the 33 ⅓ series, attempts to answer a simple question: How could Wilson, a person paid to have opinions on music, find a pop icon as ubiquitous and revered as Celine Dion so awful? He undertakes a historical and geographical survey attempting to crack the lock on middlebrow culture, the naive guilty pleasures of Thomas Kincaid and Oprah’s Book Club. His is the timeless search in the competing ethics of poptimism and rockism, the ticking of Disco Demolition Night. He is High Fidelity’s Rob Fleming rifling his dinner host’s CD racks for a mark, or David Herman’s character in Mike Judge’s Office Space, a web-coding misfortunate named Michael Bolton, despairing, “Why should I change my name? He’s the one that sucks!”

One of Wilson’s earliest clues is the concept of schmaltz, a mainstay in pop from Tin Pan Alley through Manilow and Streisand. “Schmaltz is an unprivate portrait of how private feeling is currently conceived,” he writes. “Under the surface of popular music, greasing its rails, the secret history of schmaltz runs in oleaginous currents, awaiting deeper exploration.” This might explain why Cole’s dramatic, unspecific accounts can taste like Kendrick’s, even if once digested they offer the nutritional value of fast food.

The Ringer’s Shea Serrano has written at length on the J. Cole phenomenon, and attributes Cole’s appeal to the Barnum effect, “the observation that individuals will give high accuracy ratings to descriptions of their personality that supposedly are tailored specifically for them but are, in fact, vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people.”

“I don’t think he’s actually relatable,” Serrano wrote last month. “I think he’s a familiar version of relatable, which people confuse with the real thing.”

J. Cole is, of course, thoroughly middlebrow, and his steadfast maintenance that he is the highest of the highbrow is perhaps his most grating quality: on record he has proclaimed himself the equal of Rakim and Ice Cube as well as a superior to Slick Rick and Big Daddy Kane. Yet his broad empty-calorie appeal bears likeness to the one Wilson perceives in American Idol and Celine Dion.

“American Idol attracts critical venom almost as much as Celine herself, and for many of the same reasons,” he writes. “For all the show’s concentration on character and achievement, it is not about the kind of self-expression critics tend to praise as real.”

Instead, Wilson writes, it celebrates “‘Authentic inauthenticity,’ the sense of showbiz known and enjoyed as a genuine fake, in a time when audiences are savvy enough to realize image-construction is an inevitability and just want it to be fun. ‘Authentic inauthenticity’ is really just another way of saying ‘art,’ but people caught up in romantic ideals still bristle to admit how much of creativity is being able to manipulate artifice.”

Despite Dion’s complex Quebecois identity, Wilson notes that her multilingualism eschewed immediate regional characterization, and survey data suggested that her listeners were disproportionately likely to be poorer, older, uneducated, widowed, and/or LGBTQ, a practical silent majority of disaffected mankind. J. Cole is biracial and from North Carolina, effectively anywhere and nowhere, a “living here in Allentown” blank canvas for whatever reflections on society he wishes to make. He is 32 but looks and sounds 23, and is a southerner who raps like a New Yorker, except when he raps like 2Pac, when he’s not rapping like Kendrick or Drake.

As others have already written, 4 Your Eyez Only is better than it ought to be, which, paradoxically, is really the best thing one can say about it. It is leaps and bounds better than 2011’s Cole World: The Sideline Story and 2013’s Born Sinner. It contains some adequate 2Pac karaoke, and the best songs have a dusty vinyl warmth, which inspires the stark intimacy suggested by the album title. Cole is still not nearly as profound as he thinks he is, and needs coaching on the concept of “show don’t tell”: when he says he wants to cry, the listener mostly has to take him at his word. The chorus of the third-act ballad “Foldin’ Clothes” repeats the stone-faced proclamation, “I want to fold clothes for you.” (Sexy!) It’s an atmospheric record with competent scene-setting, and although its characters are types, so are most actual people. Cole has improved considerably, but probably shouldn’t have been afforded the opportunity.

In Let’s Talk About Love, Wilson relays an anecdote from the 1998 Academy Awards in which the late Elliott Smith, himself a detractor of Dion’s, encountered her backstage and found himself floored by her ineffable charm and generosity, saying afterward, “It was too human to be dismissed simply because I find her music trite.” Sure, her music sucks, but don’t we all?