Go To School And Join The Circus

From big tops to aerial silks—how is professional circus school changing the industry

Moffat Street, on the eastern border of Brooklyn’s Bushwick neighborhood, is framed by a long parallel of tall, square warehouses. Some of the buildings have been repurposed into housing; some are abandoned; some still have industrial uses, or serve are storage spaces. Save for an adjacent metal bike rack spelling out the word “CREATIVE,” it would be entirely possible to ignore 350 Moffat, a former metal foundry now home to a circus school called The Muse.

From 2010 through the end of 2014, The Muse was located on the Williamsburg waterfront, at Kent and South 1st Streets, but was eventually forced out of its space by the landlord, to make way for the Vice Media neighborhood takeover. The space is is 7,000 square feet — seven times the size of The Muse’s previous location — and most of the space is unobstructed by walls or dividers. Hanging from a forty-foot ceiling, on any given day, is a combination of circus contraptions: lyra hoops, ropes, trapezes, a harness bungee, a Chinese pole, aerial straps, and a hammock.

I visited on a Tuesday in August, around 5p.m., and most of the patrons were working out on their own, or with a partner. The Muse advertises itself as “Home of the Working Professional,” which is not a jab at the nine-to-five workforce, but rather, an invitation for New York City’s community of professional circus artists. Angela Butch, The Muse’s founder and director, said, “During the day we really cater to the working professionals and the circus community… And then during the evening, you’ll see some of those same professionals teaching our classes, which are designed for recreation and fitness.” The clientele is about a fifty/fifty split.

The Muse is part of a growing trend of institutions providing a circus education, and in most ways, it is a very typical American circus school. Within the circus arts community, there has been a rise in schools targeting professionals as well as a proliferation of educational opportunities for amateurs, intermediaries, and the curious. In the past few years, New York City alone has seen the emergence of several schools, including Aerial Arts NYC, Circus Warehouse, Urban Circus, The Muse, and Streb.

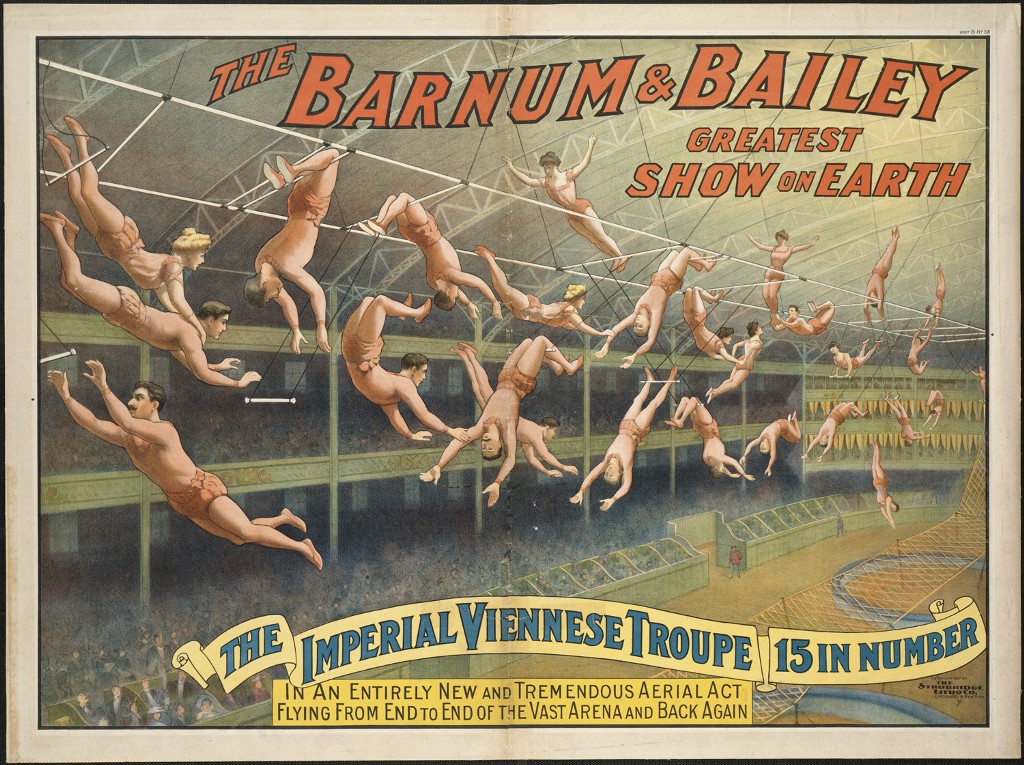

Historically, there were two pathways to joining the circus. You were either born into the circus, or you could run away with it. And the mechanics of running away with the circus were never romantic. Shoveling manure, manning a concession stand, or other mundane and often dangerous tasks — such as rigging or dealing with animals — were the primary entry into the show. From there, you had to convince someone to teach you a trick or help you cultivate a talent, but by and large, circus skills were largely procured through generational transmission for almost two hundred years.

But in 1968, Ringling Bros. began to eschew this tradition of generational transmission. Although their troupe was a highly celebrated act, Ringling’s clowns were getting old, and could no longer perform the stunts that were requisite for entertaining the masses. So they decided to educate a new generation of clowns, and opened the first clown school, “Ringling Bros. Clown College.”

If you weren’t born into the circus, clown college “was one of the first ways to get involved, and to learn the different circus skills,” said Rodney Huey, a circus historian, a circus public relations professional, and a professor of cultural studies at Lynchburg College. And it wasn’t just clowning — they taught “wire walk, low wire walk, unicycle, and juggling.” Ringling Bros. Clown College closed in 1997, but its existence established the idea that clowning and circus are art forms which can be studied, emulated, practiced, and refined.

Although the circus has evolved away from Ringling Bros.’ animals and carnival music, towards the character-driven, theatrical, and narrative approach popularized by Cirque du Soleil, circus schools continue to be a feeder for professional circuses. “Any good school wants their students to be employed upon graduation,” said Stacy Clark, a talent scout and the head of acrobatic casting for Cirque du Soleil. “It’s in their best interest to have a positive relationship with us, as much as we want a positive relationship with them.” She continued, “We will have pre-identified some students who might be a great fit for the coming needs of Cirque du Soleil, and once they officially graduate, and they are on the market, then we will approach them as independent professional artists.”

The most prominent example of this relationship is Montreal’s École nationale de cirque (ENC), one of the oldest circus schools in North America. ENC is located across the street from Cirque du Soleil’s corporate headquarters, and, within the circus arts community, has the reputation of being a feeder school for Cirque du Soleil. Clark confirmed this, saying, “ENC tends to produce exactly the type of artists that we’re looking for, given the nature of our shows, and the demands that we have at Cirque du Soleil. So it’s simply a good fit.”

One of the most tangible services a circus school can provide is assistance in the creation of an act. Kyle Driggs, a graduate of ENC, stressed the importance of circus school in the formation of his act, which combines movements based in modern dance with a juggling routine. “I started juggling these white rings and an umbrella three months before coming to ENC. And so I came into circus school saying, ‘This is what I want to do.’ Luckily, the school was behind that.” Kyle’s talents are now featured in the opening routine at Cirque du Soleil’s Paramour show in New York City.

Of the twenty circus performers in Paramour, eight of them went through ENC, one went to a circus school in China, and the rest came from gymnastics or sports backgrounds. This is fairly representative of how many Cirque du Soleil performers come from circus school; Clark added, “I would expect that number to continue to grow.” Even smaller, newer schools like The Muse supply the circus industry with performers. In addition to bookings for parties, Angela also does scouting and castings for events that desire a circus aspect — she said it’s one of the main reasons professionals come and train at The Muse on a daily basis.

There is no prerequisite body type for joining the circus; different people are suitable for different positions. Jugglers, acrobats, tumblers, trapezists, clowns, rope walkers, and aerialists are all part of any good circus. And although prior knowledge of dance or acrobatics is helpful, most circus professionals I spoke with stressed that the main barrier to becoming a professional circus performer is the requisite time commitment. Even so, circus skills are not easily acquired.

In the two hundred year history of the circus, there has never been an easier time to join, and there has never been a time where circus skills are in such high demand. This is not to say that the circus industry is not competitive, or that learning circus is easy, but a full-time career in contemporary circus is doable. Part of the growing demand for circus performers stems from a growing demand for circus to be integrated with other art forms, and this increased demand has largely fueled the continuing proliferation of circus schools.

In the past decade, commercials, Superbowl Halftime shows, music videos, musical theater, and live concerts have all started to incorporate aspects of circus performance. Julia Langenberg was performing full-time as an aerialist at SeaWorld before heading to the New England Center for Circus Arts (NECCA), from which she graduated in 2013. She told me, “When I started ten years ago, there wasn’t as much knowledge as there is now about proper training and progressive skill building. Ten years ago, employers were just looking for gymnasts or dancers that they could train without any previous circus knowledge…nobody really knew what they were doing, so to be able to go to NECCA, and have that foundational skill level, that I had initially missed, was really important.”

In addition to teaching the requisite skills for integrating circus with other forms of art and entertainment, circus schools provide qualifications that can be used to verify a potential candidate’s skill level. Langenberg said that it used to be possible to gain employment in a circus-type role at a place like SeaWorld with only a background in acrobatics or gymnastics. Now, either circus school or a long career in the circus industry is a prerequisite for those types of jobs.

One of the ideas that circus school has embedded in the circus industry is that the circus is an art form on the same level as ballet, opera, or theater. In the late 1990s, the United Kingdom and Australia began developing Bachelors of Circus Arts programs, with degrees are awarded by public universities. A bachelor’s degree in circus arts might sound ridiculous, but is it any crazier than any other bachelors or masters degree in the arts? Circus schools offer students the ability to train and learn circus arts in a controlled environment, with a literal and figurative safety net. We have BAs, BFAs, MAs, and MFAs for almost every other imaginable artistic practice, and there is perhaps no other art form that puts your life in imminent danger in the way that the circus does. I asked Stacy Clark from Cirque du Soleil, jokingly, if we would see an MFA in Circus Arts in the next few years, and she replied, in earnest, “I’m pretty sure that will be the case.”

Jack Lowery is a retired dog walker.