Soul Food: Cookbooks As Literature

Soul Food: Cookbooks As Literature

“Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.” — Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

Alexandre Dumas père was a terrible and a wonderful man. He fought in wars, hunted, traveled the globe, owned a theatre, dabbled in politics and revolutions here and there, and was bankrupted a few times after spending fortune after fortune on women and high living. And he wrote, and wrote, and wrote, in jail or out of it. With the aid of a number of assistants he was able to turn out over 600 books before the end. He was magnificently ugly, and, apparently, irresistible. Which actually, I don’t doubt that for a minute.

Dumas was also a dedicated cook and the author of a fine book on gastronomy, the enormous Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine. (That link takes you to the 1873 first edition, which is in French; I can recommend the 1958 English translation and abridgement by Louis Colman, a gentle and sensitive prose stylist who is also possessed of the requisite salacious edge.)

After emerging from under a series of crushing debts, Dumas set out to write this book “as a diversion” in the late 1860s. But then he got really into it, and wound up taking many months over the research and writing. In the dedication of the book to the novelist and critic, Jules Janin, he described his thorny legal troubles, and concluded: “In my contract with Michel Lévy, I had retained the right to write a cookery book and to sell it to whomever I pleased.”

The Regency was a charming period in France. For seven or eight years one lived to drink, love, eat. Then one fine evening the Regent was talking with Mme de Falaris, his little crow, as he called her. His head was heavy, and he laid it on the shoulder of the beautiful courtesan, saying, “Do you believe in hell, sweetheart?”

“If I go, I hope to find you there,” she said.

He did not answer. He was there already.

This anecdote is succeeded by an excellent recipe for salad dressing. “I made a salad that satisfied my guests so well that when Ronconi, one of my most regular guests, could not come he sent for his share of the salad, which was taken to him under a great umbrella when it rained so that no foreign matter might spoil it.” Dumas makes the dressing right in the salad bowl; one hard-cooked egg yolk for each two persons, mashed with oil and mixed with chervil, crushed tuna, macerated anchovies, etc., “and my servant tosses it. On the tossed salad I sprinkle a pinch of paprika, which is the Hungarian red pepper. And there you have the salad that so fascinated poor Ronconi.”

To the science of kitchen and table Dumas brought taste, scholarship, appetite, wit, sensuality, bragging, brazen inconsistency and the chatty, winning, urbane style that distinguishes his novels. The Grand Dictionnaire is made up of a zillion little vignettes arranged alphabetically, as the title suggests, but their titles are so capricious that the arrangement is no help at all if you’re trying to find anything in there. That doesn’t matter. The idea is to open the thing up and dive in.

FALCON. A bird of prey, trained and used for hunting before the invention of firearms. I have eaten roasted falcon. It had a strong flavour, but not bad.

There are suggestions for preparing toads, swan (“it is made into pies”), and (with apologies to the management) bear, which the author claims has to be marinated for ages “in a cooked vinegar marinade.” For eagle, only a proscription: “The size, nobility, and pride of the king of birds do not give it a tender and delicate flesh. Everyone knows it is tough, fibrous, and evil-tasting and that the Jews are forbidden to eat it. Let us leave it to soar and defy the sun, but eat it not.”

Dumas was just like Anthony Bourdain — like a really fat 19th-century Anthony Bourdain, I mean — very proud of trying everything, eager, lively.

“Let the reader be unafraid. He is not condemned to eat a whole elephant. But next time he finds himself in possession of the trunk or feet of an elephant, we ask him to prepare them as we shall indicate, and let us know how he likes them.”

He gives wonderful potted biographies of famous chefs — Carême, Vuillemot — a disquisition on truffles, a lovely long entry for wine and this, maybe the best story I’ve ever read in a cookbook:

TOAST. Toasts were first drunk in France at the time of the Revolution. The name comes to us from the English, who, when they drank anyone’s health, put a piece of toast on the bottom of the beer pot. Whoever drank last got the toast.

One day Anne Boleyn, then the most beautiful woman in England, was taking her bath, surrounded by the lords of her suite. These gentlemen, courting her favour, each took a glass, dipped it in the tub, and drank her health. All but one, who was asked why he did not follow their example.

“I am waiting for the toast,” he said. Which was not bad for an Englishman.

***

The cookbook author rarely confines himself to the kitchen; whether consciously or not, his work may also prove to be a study of manners, or aesthetics, or social climbing, or politics, or it may be a comic work of a very high order. But like the Grand Dictionnaire, any good cookbook is likely to be mainly a work of moral philosophy. The means by which virtue and happiness are related has been one of philosophy’s chief concerns from classical times onward; as the Socratic scholar Gregory Vlastos once wrote, “how man should live is every man’s business”; and any thoughtfully written cookbook, concerned as it must be with the satisfaction of one of our deepest needs, will have gone into this matter deeply.

Dumas, for example, an incorrigible voluptuary whether in literature, wine or romance, was the kind of person who pours every bit of himself into this moment, now: this single taste, this laughter, the scent of a single flower; this woman, this company, this night. I am a little bit in awe of his unrestrained “being in the moment,” which is a kind of mindfulness, though it is the obverse of the ascetic, Buddhist or Eckhart Tolle variety. It’s the kind of “being in the moment” that keeps nothing back, that spends everything now, that gives itself over completely, body and soul.

I admire the brio of Dumas very much, but I can’t live that way. I much prefer the model of Elizabeth David, whose cookbooks provide a better provisional answer to the question of how to live than Plato or Kierkegaard or Richard Rorty ever could.

David’s personal life was kind of a minefield. She was a libertine, a black sheep really, from a rich aristocratic English family whom she scandalized first by running off to be an actress, and then by taking off on a boat for Greece with her married lover. But it’s not the story of her personal life that calls forth my devotion; it is her writing, her cooking, her appreciation of the world and the way of life she proposes to the reader. Here the taste for pleasure is restrained, disciplined. Where Dumas is all about the overkill, in David’s view excess equals vulgarity or waste, whether in writing or in cooking, and there isn’t a speck of it in her work. Yet the effect is one of nonstop beauty, pleasure and profusion; she is all elegance and economy, and wit as dry and cool as champagne.

Staying in Toulouse a few years ago, I bought a little cookery book on a stall in the marché aux puces held every Sunday morning in the Cathedral Square. It was a tattered little volume, and its cover attracted me. In faded pinks and blues, it depicts an enormously fat and contented-looking cook in white muslin cap, spotted blouse, and blue apron, smiling smugly to herself as she scatters herbs on a gigot of mutton. Beside her are a great loaf of butter, a head of garlic, and a wooden salt box, and in for the foreground are a table laid with a white cloth and four places, a basket of bread, a cruet, and two carafes of wine.

The promise of the cover was, indeed, fulfilled in the pages of this delightful little book, called Secrets de la bonne table […] The dishes described are not spectacular, rich, or highly flavoured, the materials are the modest ingredients you would expect to find in a country garden, a small farm, or in the market of a quiet provincial town. But it is not rustic or peasant cooking, for the directions for the blending of different vegetables in a soup, the quantity of wine in a stew, or the seasoning of the sauce for a chicken reflect great care and regard for the harmony of the finished dish. This is sober, well-balanced, middle-class French cookery, carried out with care and skill, with due regard to the quality of the materials, but without extravagance or pretension.

She wasn’t uniformly crazy about all things French, though.

Torn, most willingly, from an English boarding school at the age of sixteen, to live with a middle-class French family in Passy, it was only some time later that I tumbled to the fact that even for a Parisian family who owned a small farm in Normandy, the Robertots were both exceptionally greedy and exceptionally well fed. Their cook, a young woman called Léontine, was bullied from morning till night, and how she had the spirit left to produce such delicious dishes I cannot now imagine. Twice a week at dawn Madame, whose purple face was crowned with a magnificent mass of white hair, went off to do the marketing at Les Halles, [returning] at about ten o’clock, two bursting black shopping bags in each hand, puffing, panting, mopping her brow, and looking as if she was about to have a stroke. Indeed, poor Madame, after I had been in Paris about a year, her doctor told her that high blood pressure made it imperative for her to diet. Her diet consisted of cutting out meat once a week […] On Wednesdays, the day chosen, Madame would sit at table, the tears welling up in her eyes as she watched us helping ourselves to our rôti de veau or boeuf à la cuillère. It was soon given up, that diet.

A cookbook is liable to reveal the inner workings of an author’s mind far more clearly than the most barefaced tell-all memoir could dream of doing. The form itself forces him to reveal so many intimate features of his own character; is he methodical, patient? Can he describe well (but not too minutely) the techniques required in order to achieve some particular effect? How fussy is he? Has he taste, humor, discernment? You can’t fake this sort of stuff as easily in a cookbook as in a novel, because you must be specific in the last degree; no finessing. Is the author a snob? The answer to this question is impossible for the cookbook author to conceal, try as he might. Martha Stewart, for example, is a titanic snob, and her clenched-teeth attempts to seem friendly and accessible have ever been doomed, much as I admire her skill and perfectionism (a lot).

By contrast, Irma S. Rombauer, the original author of the The Joy of Cooking is the matiest, most hilarious companion and teacher anyone could hope to have in the kitchen (just look at her!). Make sure to get the oldest Joy of Cooking you can lay your hands on; mine is a 1953 one, and I do not doubt that the versions published in 1931, 1936, 1941, 1942, 1946, 1951 and 1952 are all equally entertaining and informative. But the newer models, edited and re-edited after Mrs. Rombauer passed on to the great Kitchen in the Sky in 1962, are all but unrecognizable.

Mrs. Rombauer’s sunny, enlightened presence has, alas, slowly faded not only from modern versions of her book, but from the world at large. There may be no one left like the original Rombauer. Such modesty and charm she had. “For years I was unfortunate in having what a foreign woman called ‘a preconceited idea’ in connection with all recipes calling for yeast.” “Watch your fingers!” she shouts.

Henriette Davides, the German counterpart of the fabulous English Mrs. Beeton, says that the heat under this pancake must be neither “too weak nor too strong,” that it is advisable to put “enough butter in the skillet but not too much” and that the best results are obtained in making no more than a 4-egg pancake at one time. Henriette’s recipes make mouth-watering reading. That, as Archie of “Duffy’s Tavern” would say, is the “ipso,” but “facto” is that they are almost impossible to follow. Only a strongly intuitive person on speaking terms with his imagination has a chance of success.

(Martha Stewart, one feels sure, would never admit to so much as a stray peanut-butter cookie inadvertently scorched at the age of seven.)

Mrs. Rombauer wears her mantle of greatness so lightly, so easily. She does not shrink from steaming brains with you, nor drawing wild birds, nor squirting paper cornucopias full of icing into daisy shapes (“although the botanist might not recognize these structures as such”), and never in 1,013 pages does her giddy bonhomie fail her.

Our own neurotic age is in danger of losing the graceful art of tempering competence with such gentle self-deprecation. Now what have we got, some irritating Microsoft kazillionaire/patent troll demanding 600-plus clams so he can tell you how to make freeze-dried lobster tail. Though it must be said that the works of Mark Bittman, Nigella Lawson and Jamie Oliver retain something of Mrs. Rombauer’s classically friendly DIY appeal.

“My roots are Victorian,” Mrs. Rombauer writes in the foreword to The Joy of Cooking, “but I have been modernized by life and my children.” Modernization in Mrs. Rombauer’s case extended to such newfangled contraptions as the home freezer (“Excess air within the frozen food package is a real enemy”). Her chapter on Frozen Foods is still the most detailed and useful primer on this confusing subject I have seen anywhere; and best among its many virtues, it begins with one of the most charming passages in modern letters:

We are indebted to an Arctic explorer for the following Eskimo rule for a frozen dinner:

“Kill and eviscerate a medium-sized walrus. Net several flocks of small migrating birds and remove only one small wing feather from each wing. Store birds whole in interior of walrus. Sew up walrus and freeze. Then two years or so later, find the cache if you can, notify clan of a feast. Partially thaw walrus. Slice and serve.” Simplicity itself.

The loveliest thing about this formidable recipe is Mrs. Rombauer’s tacit acceptance of the idea that one might easily lose track of a frozen walrus in two years’ time; a contingency totally excluded from the dream universes of our modern arbiters of taste. Real cooking, like real life, is full of such accidents; Mrs. Rombauer understood this, and reveled in it.

***

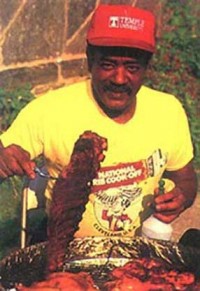

In the novel 2666, Roberto Bolaño considers two real-life authors who recalled themselves to reality by writing cookbooks. One is the 17th-c. Mexican poet, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, and the other is Barry Seaman, who is a reimagining of Bobby Seale, co-founder with Huey Newton of the Black Panthers and one of the Chicago Eight (who became Seven, after Seale’s indignation in the courtroom reached such a pitch that the judge had him bound and gagged right then and there — in the courtroom — severed him from the trial, and sentenced him to four years for contempt of court.)

At one point in the novel, Barry Seaman gives an extended account of his life after jail. In tone it falls somewhere between sermon and memoir.

[O]ne day I realized there was one thing I hadn’t forgotten. I hadn’t forgotten how to cook. I hadn’t forgotten my pork chops. With the help of my sister, who was one of God’s angels and who loved to talk about food, I started writing down all the recipes I remembered, my mother’s recipes, the ones I’d made in prison, the ones I’d made on Saturdays at home on the roof for my sister, though she didn’t care for meat. […] I learned how to combine cooking with history. I learned to combine cooking with the thankfulness and confusion I felt at the kindness of so many people, from my late sister to countless others. And let me explain something. When I say confusion, I also mean awe. In other words, the sense of wonderment at a marvelous thing, like the lilies that bloom and die in a single day, or azaleas, or forget-me-nots. But I also realized this wasn’t enough. I couldn’t live forever on my recipes for ribs, my famous recipes. Ribs were not the answer. You have to change. You have to turn yourself around and change. […] So those of you who are interested can take out pencil and paper now, because I’m going to read you a new recipe. It’s for duck à l’orange.

This passage is very close in feeling to the actual book, Barbeque’N with Bobby, which yes, is a real cookbook written by Bobby Seale in 1982. Seale steers pretty well clear of politics in the text, but there are hints, as in the acknowledgements to colleagues, friends and family: “I thank them in the spirit, realization, and principles of cooperational humanism.” Seale seems to have mellowed out in much the way Bolaño suggests, and there’s a humility and humor to his book that is fascinating and powerfully attractive. I haven’t tried the recipes yet (they are very involved, with five pounds of meat at a go being about the minimum per recipe, hot marinades, liquid smoke and all that jazz) but they look awesome. Meaty! But awesome.

The author who aims at literary glory in the conventional way, say by writing an immortal novel or a definitive biography, is apt to price himself out of the market regarding practical solutions to the problems of daily existence. Jim Behrle addressed this with great elegance in an essay he wrote for the Poetry Foundation: “Most of the True Genius poets can’t tie their own shoes. They are beautiful creatures — too beautiful to exist on earth and, for example, eat soup.”

Dumas, and Elizabeth David and Julia Child, Marcel Boulestin and Alice B. Toklas and Bobby Seale and so many others, have the eating of soup figured out and a good deal besides; as literary artists and beyond this, as artists of savoir faire, of life itself. Given that one must eat, how then to do it? Historians and philosophers as well as poets tend to come up short where advice on questions urgent and as homely as these is required. Nor do the feral rich (a serviceable phrase coined in the recent London riots) or those who serve them appear to know much of interest about these things. The rich must always believe that elegance and wisdom are there for the buying, and by their ostentation and excess demonstrate only the lack of taste and sense, rather than the possession of either.

Man that is born of woman hath but a short time to live, and the great authors of gastronomy offer us all an explicit and conscious acceptance of this temporality, of the demands of the flesh. They teach us to embrace sensuality not only because we are drawn to it, but also because we are condemned to it; a condemnation which, it turns out, may be borne both humbly and happily.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.