How To Be Werner Herzog

What A Six-Hour MasterClass™ Can (And Can’t) Teach You About Making Movies

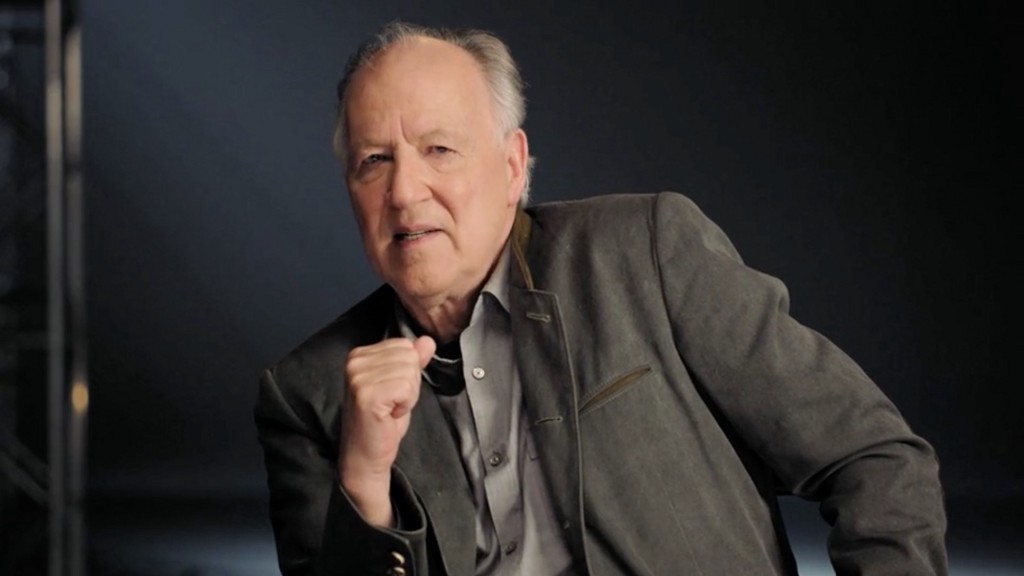

I have found that when I tell people I love Werner Herzog, the sentiment is easy to misinterpret. It can sound like banal garden-variety hipster fandom of a public eccentric. It has become hard not to view Werner as a kind of self-caricature, a benevolent maniac with an unignorably comical speaking voice, the guy who does things like somehow get shot during an interview and then say, “It is not a significant bullet.”

That voice in particular does not allow you to forget for a moment his fundamental strangeness. His delivery is a fervent rasp, his pronunciations inhumanly precise. Each word seems to require profound concentration and effort. The emotional range of his voice is strikingly narrow, and yet it also lives in a place that I have never heard anyone else match, a surreal and cosmic combination of the matter-of-fact and the desperately urgent.

His accent at times is pure Dada, more Martian than Bavarian. He finds preposterous multi-vowel diphthongs in what should be completely straightforward monosyllables: “day,” “work,” “how,” “dream.” Through the dogged, loving overuse of his favorite words — “insipid,” “grotesque,” “grandiose,” “banality,” “enormity,” “bozo” — he has created his own genre of diction, a collection of English’s most vivid and piquant descriptors of the (usually awful) extremes of the human experience, words clustered at the poles of the extraordinary and the mundane, language that I think of as Werneralia.

I am probably writing a little bit in that voice because I have just listened to six hours of it, in the form of “Werner Herzog Teaches Filmmaking,” a twenty-six-video series created by MasterClass.

If you love Werner, as I do, then this class is pure pleasure. I had some specific hopes going in, and each of them was fulfilled.

Does Werner talk about work with animals gone awry, and does he additionally talk shit on the intelligence of those animals?

This is my favorite thing that Werner or any human being can possibly do, and he did it a number of times. The best instance was in Lesson XII (“Camera: Techniques”), when Werner described being bitten by one of the iguanas and/or desert lizards that Nic Cage hallucinates in Bad Lieutenant. “He bit me so hard, I cannot explain. It was like a vise. The crew was delighted and laughed like mad.” Werner then gazed, momentarily wordless, at the playback of the twitchy, expressionless lizards. “These creatures are so insipid, so stupid, so demented,” he reflected. “Look at the face of that iguana. I love that creature. It just can’t get any better.” He paused, utterly transported. “I love these moments. How beautiful.” And, scene. Please trust me that it was fucking amazing. In another lesson (“Locations”), he talked about an Amazonian hut he had to share with what he describes as “two hundred guinea pigs running over me,” which I invite you to stop, close your eyes, and envision before moving on to the next paragraph.

Does Werner tell some good stories about his monstrous, cartoonishly unstable star actor, Klaus Kinski?

Indeed he does. Over the course of his career, Werner voluntarily sought out the horrific mayhem of Kinski five different times, and that incredible and baffling psychodrama is a recurring theme in this class. My favorite Kinski story was an episode early on in their relationship: young Werner sits in a theater as a teenager and watches teenage Kinski’s portrayal of Hamlet. Kinski falls silent two and a half minutes into the play, having forgotten his lines; he then works himself into a violent rage, flings a burning candelabra into the audience, and concludes his performance by rolling himself up in a carpet and remaining there until the curtain falls. Thus begins a section entitled, “What’s On-Screen Is All That Matters.”

Another time, Kinski was screaming at, and “physically hanging off,” Werner because someone had brought Kinski lukewarm coffee on the set of Fitzcarraldo, in the Amazon — the subpar coffee was apparently because the crew was preoccupied with a terrible plane crash — and Werner describes silencing Kinski thus: “I went to my hut. I had a tiny piece of Swiss chocolate left. I came back. I stepped into his face, and I ate it. And that was too much for him. That was beyond him, and he shut up.” Watching this, alone in my office, I yelled, out loud, “What?!” I paused it and rewatched it a number of times, but this story became no less enigmatic. How could eating the last piece of chocolate possibly have had that effect? That was beyond Kinski?! Herzog has no interest in telling you why or how this worked. He smiles cryptically, and moves on. This was, of course, the conclusion of the section “Controlling Your Actors.”

Will the pedagogy feel true to Werner’s sensibility?

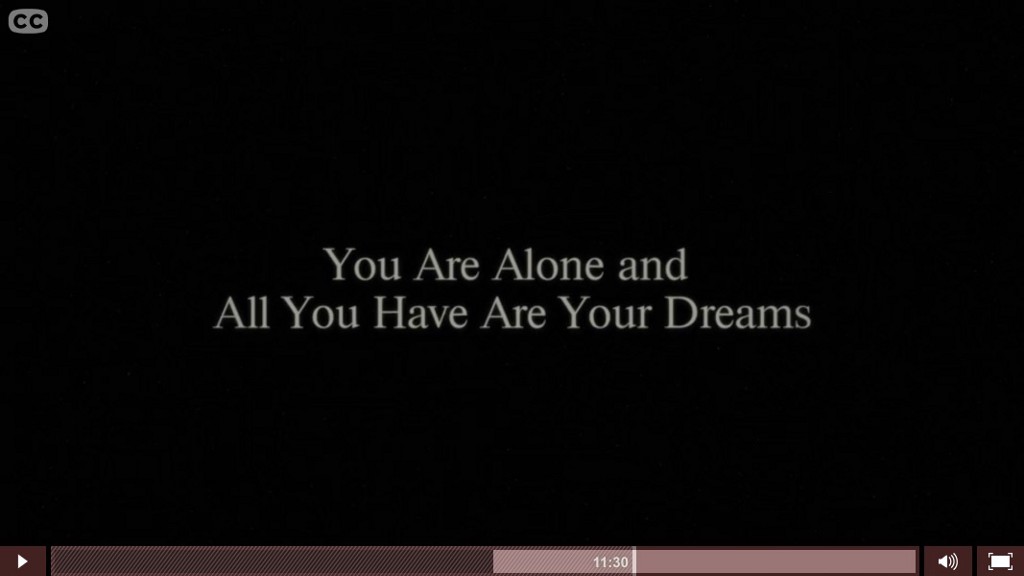

There is no chance that Werner wrote it himself, but the course’s written materials did often seem to be written by a committed Herzogist. Lesson headings included:

Be Ruthless With Your Footage

Disorient Your Audience

Make Catastrophes Part of Your Story

Learning Editing from Icelandic Poetry

Knowing the Heart of Men

Collect the Remarkable, Not Garbage

and of course, You Are Alone and All You Have Are Your Dreams, which I am sure you think I am making up, but I am not.

The assignments, too, felt reassuringly true to Werner’s vision. For example: “Werner once made a three-week journey by foot from Munich to Paris in the winter of 1974 to visit a dying friend. It’s time for your own journey. Try to travel a significant distance by foot sometime in your life for an essential reason.” Or this: “Spend a night in the forest, as Herzog prescribes. Stay from dusk until dawn, and listen for sounds and record moments that you feel inspired by.”

I am ashamed to tell you that I have not yet completed either of these assignments.

Will Werner talk shit on people in addition to animals?

This happened with enjoyable frequency and abruptness. Film students who don’t read books will be “mediocre at very best.” Screenwriters who rely on three-act structure are “brainless, really brainless.” His “heart sinks” when filmmakers tell him they shot hundreds of hours of footage, because “it means you don’t know what you are doing.” Anyone who cares too much about their visual style is “artsy fartsy” and “always close to kitsch.” Anyone who cares too much about market research is lost “in a labyrinth of stupidity.” He becomes almost Trump-like while reflecting on the criticism he has faced for falsifying quotations and scripting scenes in his documentaries: “Those who start to put me down over doing something like this, I have an answer. You are all losers. Happy New Year.”

I could go on and on. It was a supremely enjoyable six hours. Was it educational, though? Did he, in fact, teach filmmaking? I am in a decent position to judge this, preparing as I am to direct my first film, and I have to tell you: I am not so sure.

As he reminds you at every stage, he is completely self-taught, and I think as a consequence his lessons tend to be far more philosophical than technical: seek the extraordinary, get outside of yourself and engage with the real world, be self-reliant and adaptable, do as much yourself as you possibly can.

Read widely. “Read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read. Read. Read.” Yes, he said that word eleven times in a row. But it’s a good principle, and so is this: Never ask anything from someone that you wouldn’t do yourself. If you want Christian Bale to eat maggots, you have to at least offer to eat some too. (Bale, graciously, told Werner that wouldn’t be necessary; he then ate maggots for two uninterrupted minutes, unaware that Werner was not going to yell “Cut.”)

Sometimes there are specific rules of Herzog’s set that sound to me worth borrowing. No cell phones within two hundred feet of any camera, for example. No director’s chair or trailer. Do the slate and last looks yourself, to stay close to the actors and protect them from distractions. Always start shooting ninety minutes after call, no matter what.

Other rules sound frankly insane, like his aversion to storyboards (“an instrument of the cowards”) or any screenwriting process that takes more than five days (he cites Aguirre, the Wrath of God, much of which he wrote drunk, on a bus, with his soccer team, “chanting and vomiting on my typewriter”). I will definitely be storyboarding my movie pretty carefully, and my script took years to write, and despite Werner’s disapproval, I am pretty okay with both of those things.

But honestly, any inquiry into how usefully this class teaches filmmaking is unavoidably silly. It is six hours with a self-taught filmmaker who does not really believe this stuff can be taught, who wants you to find your own answers, your own questions, your own curriculum.

I am also self-taught, and I find myself agreeing with him. Young writers ask me for advice sometimes, and everything I tell them is uselessly abstract — encouragement to go out there and fail and learn from it, vague declarations that the craft is everything, that the process and not the outcome is what you must perfect.

I hear myself and cringe. But to be more specific is to begin to tell them how to write like me. They don’t want that. Even if they do, they shouldn’t. And so it feels intuitive and right to me that this series does not really function as a class — more as an artist’s autobiography and manifesto. I think really any so-called class in artmaking must.

Werner knows this. He leans gleefully into it. He tells you the stories of his life, but you must unpack them on your own. He does not explain to you why the chocolate silenced Kinski. He does not tell you why he finds an animal’s stupidity so beautiful. He does not give you a means of conceiving a film. Instead he gives you a metaphor. Films, he tells you, are home invaders, preformed things that stumble uninvited into his mind. “You wake up,” he says, “five men are in your kitchen. How they got in, you don’t know. But one of them comes swinging wildly at you. So you better deal with that one first.”

And he cannot tell you how to deal with the invader, taking a swing at you. He cannot teach you to make the art that only you can make, to share the dreams that only you can dream. You had better teach yourself.

There is perhaps one thing he can teach you, and that is how to be Werner Herzog. But look into those sunken lakewater eyes. He knows you are not up to it.

Jesse Andrews is a novelist and screenwriter. He is the author of the New York Times bestseller Me and Earl and the Dying Girl and the screenwriter of that book’s Sundance Grand Jury Prize–winning feature film adaptation. His most recent book, The Haters, was recommended by a Times reviewer for “readers who… like human effluvia.”