The Cuckold Surgeon's Heinous Revenge

by Willy Staley

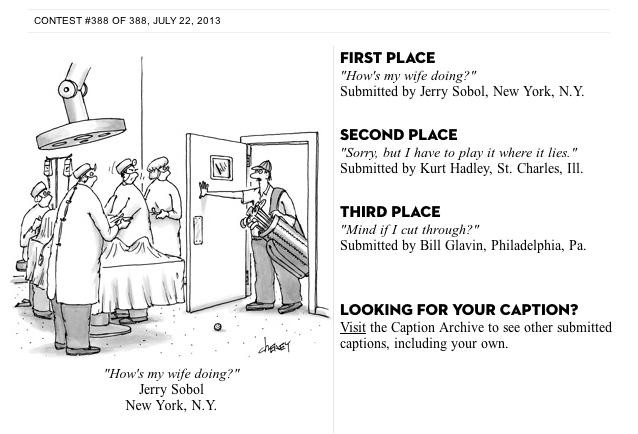

The winning submission to The New Yorker’s cartoon caption contest #388, by Jerry Sobol, of New York, N.Y., appears to the lay reader, or the person in need of glasses, to be a simple joke about how careless middle-aged men can be about their spouses. A closer read reveals a dark, Cheeveresque narrative penned by Sobol, who likely harbors retrograde opinions about women’s place in the world that would horrify the average New Yorker reader.

A chinless man carrying a bag of golf clubs and wearing golf clothing, has burst into a surgery, perhaps while attempting to locate a stray shot (whether he is playing golf within the hospital or nearby is immaterial, though both, we must point out, seem equally absurd). The surgeon and his support staff look on, dumbfounded. The man asks: “How’s my wife doing?”

Classic. Famously described as “a good walk spoiled,” golf is so much more than that to a certain breed of American men. It is an affair without the affair. A long-running poker game without the disgusting cigars (well…). The sport may have become more inclusive since the Augusta National Club invited its first black member to join way back in 1990 — or, I suppose the year right before that — but rest assured that few men are happy when their wives take it up. It is a five-hour ticket away from all familial duties, which goes a long way to explaining why so many people spend so much money playing a game that is so consistently vexing and humiliating.

So the lay cartoon reader, whether male or female, hardly has to think about this — which is “the idea” of a New Yorker cartoon, after all, a quick interstitial chuckle, to give you a break from the emotionally draining narrative about a Turkish restaurant that makes Turkish people cry, or whatever. Clearly a sandbagging, Polish-joke-telling, hideous-swing-swinging scumbag golfer has taken the opportunity presented by his wife’s second breast augmentation to catch a quick round. Har-har. Whattadick! That men who golf are careless toward their wives is such a fat and juicy trope-fruit on the trope-ula tree in your average New Yorker reader’s backyard that the branch hangs so low the neighbor’s cat routinely paws at it while writhing around on its back in the way that cats do. It’s so goddamned obvious that we’d be rubes to not assume it this what it could only be: a diversion, sleight of hand — a mere layer of gloss over the hideousness that lies beneath it.

But no. Take a look at the area surrounding the surgeon’s mask.

Even a child would recognize these lines to be the universal cartoon sign for movement, indicating that the surgeon’s mask is moving, from which we can infer that he is speaking. Once you realize that the surgeon is asking the golfer how his wife is doing — and not the other way around — the scene takes on a depraved air.

Seeing past Sobol’s trickery, the story writes itself: the Surgeon works surgeon’s hours (erratic), making surgeon’s pay (handsome), enough that his wife doesn’t have to work, but, this being 2013, she’s not sure she wants kids either, and so she takes up a hobby — on a whim, golf. Part boredom, part loneliness, part just honest-to-God not-giving-a-shit, she starts sleeping with the pro. It’s not even that she finds him attractive, it’s his un-Surgeon-ness that appeals to her. You know how these things go: one second he’s helping her with her backstroke, hands around her waist, like that one scene in Tin Cup (1996), the next they’re always finding reasons to book the (private) area with the high-tech swing analysis equipment.

This goes on for some time, rather discreetly until it hits an inevitable snag. The surgeon gets called in for what he thinks will be an all-night thing — another texting-while-driving case where a kid got all intertwined with a roll of chicken wire from the flatbed that had been in the other lane — but the patient died before the Surgeon even had a chance to operate. He came home to the sound of the back door slamming, and found one of those screw-in plastic golf spikes and a combination divot-remover/yardage finder left behind on the rear patio. Why are you home so soon? his wife asked, stepping out of the shower, her hair barely wet. His beeper goes off before he can say a thing: 911. The other guy, the guy driving the chicken-wire truck, he just showed up.

Apologies if that is all a bit obvious. It’s just that some people are terribly bad at inferring what has happened just “before” the events of a single-panel cartoon unfold.

The Surgeon, furious, fools both the golf pro and the hospital staff into allowing the confrontation we witness to happen. (If you must know: by telling Golf Pro and the staff that it was the Golf Pro’s younger brother upon which he was operating. Distraught, Golf Pro was in such a hurry, he forgot to leave his clubs behind.) As Golf Pro bursts in, Surgeon’s entire staff looks up him — ruling out the possibility, which might cross a less-capable reader’s mind, that the Golf Pro is an apparition brought on by jealous rage — distracting them from the patient’s surgery. “How’s my wife doing?” says the Surgeon, scalpel in hand, chill in his voice.

Golf Pro hardly has time to reach for his six iron. We all know how it ends for the truck driver.

One cannot witness a morality play this heavy-handed without wondering about the author’s intent. Thematically, it’s practically an homage to the midnight movie favorite The Room (2003), about an affable but severely mentally handicapped Moldovan man driven to an unintentionally humorous suicide by his scheming jezebel of a bride-to-be. Just as viewers would be right to wonder if Tommy Wiseau, The Room’s auteur, harbors a deep-seated hatred of women, we must wonder the same about Sobol. Why else would he subject us to this absurd tragedy unless he wanted to teach us some lesson about how he believes women, liberated as they are now from their traditional responsibilities, bring men low?

This column typically assumes that New Yorker readership understands, or at least intuits, the deeper meanings behind the Caption Contest winners, but if that were the case here, it would be an ugly glimpse into their collective psyche. No, it’s clear the wool was pulled over both the readership and even, perhaps, the editors’ eyes: all the finalists to the contest are submissions that assume the Golfer is speaking. This widespread misreading of the cartoon concerns me, as it should any scholar of single-panel cartoons, but it also offers relief, of a sort. No, not all subscribers to The New Yorker harbor a misogynist agenda. It’s just Sobol, that magnificent trickster.

Willy Staley contributes to Shitty New Yorker Cartoon Captions.