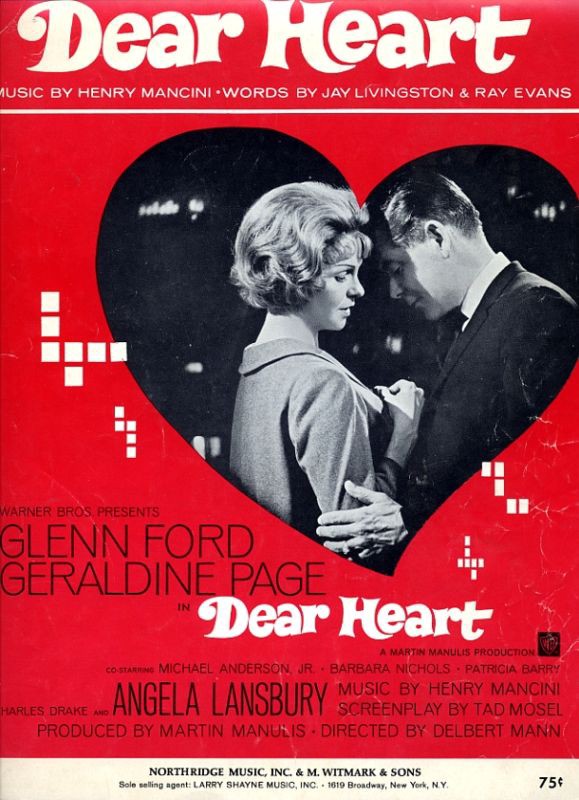

'Dear Heart' (1964)

Revisiting old books and films worth remembering.

I figured I was the only person alive who had given a second thought to 1964’s Dear Heart until last year, when I spotted it on Matthew Weiner’s annotated list, reproduced at Vulture, of ten films that influenced the creation of Mad Men:

Stumbling upon this film gave me the impetus to finally write the pilot. I was taken by this mainstream Hollywood film that reflected a very casual attitude towards sex, something that seemed uncharacteristic to my preconceptions of the era. With its glib bachelor hero and dowdy, conservative ingénue, it tells a tale of moral corruption and heartbreaking duplicity in the form of a light comedy. As Glenn Ford tries to change his ways and take responsibility for his meaningless romances in glamorous Manhattan, I found a jumping-off point for the series.

Weiner is right on two counts: the way you’ll likely find Dear Heart, a sparkling black-and-white gem directed by Oscar winner Delbert Mann, is by stumbling upon it, as I did with my tightwad’s basic-cable subscription when I was a graduate student living alone in the Midwest in the 1990s. Weiner is also correct that Dear Heart is about sex — whether sex is necessarily demeaning without affection, whether infidelity can coexist with a solid marriage, and so on. But it’s a movie about sex that isn’t trying to be sexy: its ambition is to be a romance bereft of sentimentality, may its drippy title and Mancini’s “Moon River”–knockoff theme song be damned.

Evie Jackson — it terrifies me to imagine anyone but Geraldine Page entrusted with this tricky role — is a fortyish unmarried postmaster from small-town Ohio who comes to New York for the annual postmasters’ convention. She’s all googly-eyed wonder and provincialism: she does things like tell strangers that she can guess their names (she’s always wrong) and has herself paged at the spiffy New Amsterdam Hotel for the thrill of hearing her name ring out in the lobby.

Also staying at the hotel is handsome middle-aged Harry Mork (played by Glenn Ford, whom I never paid attention to until I saw this expertly acted film). Harry is taking his recent promotion from greeting card sales to marketing as a signal to finally grow up and settle down. He’s just become engaged to a widow named Phyllis, but he’s going to squeeze in some oats-sowing before they get hitched. (Harry’s stock pickup line is to tell women that he’s psychic: he can guess what’s inside a greeting card strictly by looking at its front.) Evie is watching when Harry meets and appraises a beehived floozy, June (played with delectable idiocy by Barbara Nichols), who works at the hotel’s magazine counter. It’s enough to convince Evie to get her hair done for the convention’s evening festivities. The head-crowning result, which calls to mind a cross between a feather duster and a cow pie, is one of cinema’s great little sight gags.

Evie is determined to have a night to remember, and that doesn’t include Frank, a married man with whom she had an affair at a convention past and who propositions her again. She demurs — not just because she’s thinking of his wife, although that’s part of it — but she’s sorely tempted, especially as three shrewish female colleagues with their sights set on card games and early bedtimes propose that she complete their quartet. With her aversion to corrupting influences and her ditzy extemporaneous effusions of kindness — to perfect strangers Evie announces “I like your wig” and “I like your beard” — she calls to mind “All in the Family”’s Edith Bunker if she had never been shackled to Archie.

Meanwhile, Harry makes a play for June (“Do you know I have a psychic thing?”; “I don’t wanna see it”), and they decide to rendezvous when she gets off work. To kill time until then, Harry goes to the bustling hotel restaurant, where he and Evie finally meet when they’re forced to share a table. He feels compelled to mention “my wife” — she has a feeling he’s making her up — but he’s charmed by her guilelessness, and remarks at their shared interest in guessing people’s names (though he has the grace not to guess aloud).

Later that evening, Evie has a close call with a predator at her hotel room door. She runs for the stairs and makes it to the lobby, where she crashes into Harry, just returned from his tryst with June. He offers to buy her a drink and they end up carousing with the postmasters, for whom she is obviously a leading light, and whom she introduces not by name but by city or town.

The missed romantic connections continue, followed by second chances. Harry breaks their date to see the Statue of Liberty: following Evie’s example of moral rectitude, he decides to indulge in father-son time with his stepson-to-be. But Evie doesn’t get Harry’s message and is reduced to taking the fourth chair at a card table with the three party poopers.

The fourth party pooper would be New York Times film critic and legendarily tough cookie Bosley Crowther, who panned Dear Heart, lamenting what he considered the “cheap situation into which [screenwriter Tad] Mosel shoves Miss Page” and reducing the main characters to “old-maid postmaster” and “colorless clod.” That’s an awfully thin characterization of two people at fretful existential crossroads. At one point, Harry says to Evie, “That shock you? That girl and me?…It shocks me. And I’d be very pleased if you liked me enough to be shocked too.” This might not be something that Don Draper would have said to a woman, even one he respected, but he might have thought to.

I have to wonder if Crowther, who was born in 1905, was too old to appreciate Dear Heart. A movie about sex is of course about sexual mores, which are of course about gender roles, which are slippery. Patrick’s girlfriend is the one of the pair ready to have sex, which Harry can’t fathom (as perhaps Crowther couldn’t). The adult women of Dear Heart have jobs: with the post office, as artists, at the hotel; the exception is Phyllis (played with scene-stealing self-interest by Angela Lansbury), whose life seems empty. These women may want men, but they don’t need them as much as their mothers did, and unlike Harry, Evie would rather be alone than with the wrong person. She tells him in her hotel room, during a chaste visit, “I wish I could be one of those women who takes what she can have and loves it for what it is.” “But then I wouldn’t want to stay as much,” he says.

Evie isn’t giving up, although she realizes that quitting men is a not unprecedented choice for a woman her age. (“They’re after me, you know,” she says to Harry about the trio of resignedly single women looking for their dependable fourth.) Dear Heart understands that people can be particularly judgmental when it comes to women alone. Because Evie has made the mistake of showing human concern — “Are you all right?” she says when she sees the man who will try to molest her slumped against the wall outside her hotel door — he tells her, “If you’re thinking of screaming or ringing for the elevator, you just remember: you’re the one who spoke to me. We’ve got an ugly name for that in public places. Why don’t you just ask me in?” The film is remarkably attuned to the modern single woman’s plight — then as, hate to say it, now.

The film is attuned in other ways. In a nod to both plausibility and fairness, some of the hotel employees and convention goers are played by black actors — a preposterously rare occurrence in films of this era. A democratizing impulse runs throughout Dear Heart. Floozy June has the last laugh when Harry tries to pass her off as his wife to a concierge at a neighboring hotel. And the upwardly mobile Harry, on the brink of marrying into gentility, registers Evie’s fetching lack of inhibition as this working-class broad sings a daffy song about the mail with her colleagues. Evie is worthy of his white-collar affection — and, sure, worthy of sex too.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor.