Before 'Catcher In The Rye': J.D. Salinger's First Holden Caulfield Stories

by Michael Moats

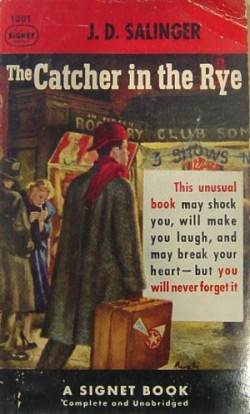

Tomorrow marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher In The Rye. This excerpt is from a longer essay, “The Real Holden Caulfield,” available at the Fiction Advocate.

It was either dumb luck or artistic excess that led Salinger to give his most sentimental and developmentally arrested character the name “Holden.” Salinger jammed his foot into the trap set by that name, and only managed to walk away because, as with everything about Holden, there is an authenticity that insulates him and his author from the annual term paper analyses that he is “holdin’ on to his innocence” or “holdin’ back his emotions.” According to one story, Salinger was walking through Manhattan some unassuming day in 1947 when he came across the marquee for the movie Dear Ruth, starring William Holden and Joan Caulfield. Side-by-side in marquee letters (in lights, as it were) were the words ‘Holden’ and ‘Caulfield.’ Another story carries over the Joan Caulfield connection, but instead claims that ‘Holden’ came from one of Salinger’s shipmates during his time as part of the entertainment crew on a cruise ship. The plot thickened in 2001 when Denver’s Rocky Mountain News printed the obituary of a man named Holden Bowler, an Idaho-born singer, ad man, 1932 U.S. Olympic athlete, and, in 1941, shipmate to J.D. Salinger on the cruise liner SS Kungsholm. According to Bowler’s widow, “Jerry told him, ‘What you like about Holden is taken from you, and what you don’t like about him, I made up.’” Salinger took no action to confirm or deny the story, nor did he ever comment on speculation that ‘Caulfield’ was pulled from Joan Caulfield.¹ Salinger’s daughter Margaret wrote that her father often complained about “giving his beloved characters ‘terrible’…names, such as Seymour, but that’s just what Seymour’s parents would have done, he said, so he had to do it even though it ‘nearly killed him.’”² So it simply may be that Mr. and Mrs. Caulfield are responsible. It may also be worth noting that the hero of David Copperfield, referred to by Holden in the opening sentences of The Catcher in the Rye, divulges in his own opening chapter that he was born with a caul. So perhaps there is some David Copperfield kind of crap in Holden’s story after all.

It’s unlikely that any of these stories gets it exactly right. Salinger began working on Holden Caulfield more than ten years before The Catcher in the Rye, which was six years before he might have come across Dear Ruth at the local cinema and at least five years ahead of Joan Caulfield’s film debut. (She did have a modeling and Broadway career before going to Hollywood, but she didn’t reach the stage until 1943. Chances are slim that Salinger would have caught her name on any marquee, or known much about her in his Kungsholm days.) The most likely of the possibilities, that Holden was named after the author’s 1941 shipmate, would mean that Salinger must have settled on the name not long before Holden’s first story, “Slight Rebellion Off Madison,” was accepted by The New Yorker later that same year.

As of 1941 there is no Allie, no Jane Gallagher and no Phoebe. There is just Holden Caulfield: an upper-middle class teenager who begins railing against the things he hates.

“Slight Rebellion” is an early, third person rendering of Holden’s date with Sally Hayes in The Catcher in the Rye. There are slight variations — Holden is home for Christmas break rather than expelled, and he and Sally spend some time dancing — but the core of the action is the same. Holden and Sally see a matinee where they “vehemently agreed with each other that the Lunts were marvelous.” They horse around in a cab. Sally tells Holden that she loves him and that crew cuts are corny. Sally’s ankles, as always, bend in awkwardly when she ice skates, and Holden is, as always, not much better. There are no hints in “Slight Rebellion” of just how much “madman stuff” Holden would get into. As of 1941 there is no Allie, no Jane Gallagher and no Phoebe. There is just Holden Caulfield: an upper-middle class teenager who begins railing against the things he hates. “I hate the Seventy-second Street movie, with those fake clouds on the ceiling, and being introduced to guys like George Harrison, and going down in elevators when you wanna go out, and guys fitting your pants all the time at Brooks.” Holden asks Sally to run away with him to the woods in Vermont or Maine. When she refuses, he leaves her at the skating rink.

The New Yorker picked up “Slight Rebellion” in November 1941 and planned to publish it to coincide with the Christmas season. The magazine was apparently intent on ruining the holidays for young readers everywhere. On December 7th, Japanese bombers attacked Pearl Harbor, drawing America into the Second World War. The next day President Roosevelt delivered his war message to Congress. New Yorker editors felt it would be poor form to publish a story about a troubled young man at a time when so many boys Holden’s age would soon be sent to the front lines. Salinger himself attempted to join the service in 1941, but was turned away because of a minor heart irregularity (no pun intended by the armed forces, I’m sure).³ This was a time for Roosevelt’s “unbounding determination of our people” and not Holden’s mopey, unguided hatred of waiting on the bus or getting fitted at Brooks. “Slight Rebellion Off Madison” was put on indefinite hold.

Salinger was undoubtedly disappointed but remained undaunted, and continued to develop Holden Caulfield in fits and starts over the next ten years. Holden shows up in two unpublished stories written in 1942, “Holden on the Bus,” and “The Last and Best of the Peter Pans.” A reference to the former exists in the “kill files” of rejected stories from The New Yorker, though no public record of the story exists today. In “The Last and Best of the Peter Pans,” Holden remains in the background of the story, which began to shape the Caulfield family that would eventually grow into The Catcher in the Rye. Vincent Caulfield, the narrator of “Peter Pans” is the oldest of the Caulfield children and the model for D.B. in Catcher. Kenneth, a younger brother who dies unexpectedly, would become Allie. Also appearing for the first time was Phoebe Caulfield. Holden, however, is mentioned only once. Today “The Last and Best of the Peter Pans,” which is in the Princeton Library and on publication embargo until 75 years after the author’s death, carries a sort of folklorish quality because it contains the first known mention of Salinger writing about a child needing to be saved as it moved towards a cliff.

In 1944 Holden made a substantial, though offstage, public appearance in “The Last Day of the Last Furlough,” printed in The Saturday Evening Post. The story is about “TECHNICAL SERGEANT John F. Gladwaller, Jr.” also known as “Babe,” and his last hours home before departing for World War II. The 1944 Babe Gladwaller (God only knows where Salinger got this name) seems like a revision of the Holden Caulfield deemed unfit for public consumption in “Slight Rebellion Off Madison.” Babe’s angst is more understandably focused on the things he loves and hates to leave behind: his books, his snow-covered neighborhood, his younger sister Mattie. Holden sulks over “fitting your pants all the time at Brooks,” while Babe is morose and introspective about going to war to defend these things, cataloging the inevitable search that likely engages every soldier on the eve of shipping out, the questions of why we go to war at all.

What protects “Last Furlough” from melodrama is the presence of Babe’s Army buddy, Vincent Caulfield. Vincent has “a kid brother in the Army who flunked out of a lot of schools. He talks about him a lot. Always pretending to pass him off as a nutty kid.” While Babe anticipates fear and loss, Vincent’s got the real thing: his brother Holden has gone missing in the Pacific. This, then, was the first published mention of Holden Caulfield. He is 20 years old, nine years younger than Vincent and — somehow — taught biology before enlisting in the army. But the Holden of Catcher is there, as Vincent tells Babe:

“I used to bump into him at the old Joe College Club on Eighteenth and Third in New York. A beer joint for college kids and prep school kids. I’d go there just looking for him, Christmas and Easter vacations when he was home. I’d drag my date through the joint, looking for him, and I’d find him way in the back. The noisiest, tightest kid in the place. He’d be drinking Scotch and every other kid in the place would be sticking to beer. I’d say to him, ‘Are you okay, you moron? Do you wanna go home? Do you need any dough?’ And he’d say, ‘Naaa. Not me. Not me, Vince. Hiya boy. Hiya. Who’s the babe’ And I’d leave him there, but I’d worry about him because I remembered all the crazy, lost summertimes when the nut used to leave his trunks in a wet lump at the foot of the staircase instead of putting them on the line. I used to pick them up because he was me all over again.”

In May 1944, two months before the publication of “Last Day of the Last Furlough,” Salinger wrote a letter to his mentor, Whit Burnett, the editor of Story magazine, saying that he had about six Holden Caulfield stories on hand. What happened to them is unknown. Holden continued to appear in pieces between 1944 and 1946, but mostly through the eyes of his brother Vincent. He showed up, through a letter and briefly in person, in “The Ocean Full of Bowling Balls,” an unpublished story from 1945. “Bowling Balls” is Vincent’s recollection of the last day of Kenneth Caulfield. Kenneth, like Allie, was a lover of baseball and poetry and wrote his favorite lines on his glove. His red hair could be spotted from across a golf course. And like Allie, he was frail, diagnosed with medical issues related to his heart. In the story, Kenneth dies after being struck by a wave while coming in from a swim. Holden is waiting on the porch, returned from camp and still holding his suitcases when Vincent returns home frantically seeking help for Kenneth. Kenneth dies later that night. “Bowling Balls” takes place on Cape Cod, while in Catcher Allie “got leukemia and died when we were up in Maine, on July 18, 1946.”

Holden next appeared in “This Sandwich Has No Mayonnaise,” from the October 1945 Esquire. The piece again follows Vincent, who is in Army training in Georgia, sitting in an overfilled troop transport, awaiting departure to a local dance hall. Through the din of the soldiers around him, Vincent reminisces and worries about his brother Holden, who, “can’t do anything but listen hectically to the maladjusted little apparatus he wears for a heart. My missing-in-action brother.”

The voice Salinger would eventually use to bring Holden to life is still developing at these early stages. There are far fewer curse words (Collier’s probably wouldn’t have stood for much more), and the word “slobs” appears where “phonies” would be later.

In December of the same year, Salinger published the story “I’m Crazy” in Collier’s. It was the first time readers heard directly from Holden Caulfield, and would later become the opening chapters of The Catcher in the Rye. “I’m Crazy” begins with Holden on the hill, looking for a proper goodbye from “Pentney Prep” (later “Pencey”) and describes the conversation with his history teacher, old Spencer. The voice Salinger would eventually use to bring Holden to life is still developing at these early stages. There are far fewer curse words (Collier’s probably wouldn’t have stood for much more), and the word “slobs” appears where “phonies” would be later. After the lecture from Spencer, the story jumps ahead to Holden’s return home that night. He wakes up Phoebe and plays with his infant sister Viola, who, it seems, would make this single appearance and disappear forever. In their conversation, Holden and Phoebe walk right up to the “catcher in the rye” vision, but stop short. When Holden’s parents come home, rather than venturing back into the night, Holden enters the living room to tell them he’s back, failed out of another school. The story closes with Holden facing a more clearly outlined and dismal fate than Catcher:

I lay awake for a pretty long time, feeling lousy. I knew everybody was right and I was wrong. I knew that I wasn’t going to be one of those successful guys, that I was never going to be like Edward Gonzales or Theodore Fisher or Lawrence Meyer. I knew that this time when Father said that I was going to work in that man’s office that he meant it, that I wasn’t going back to school again ever, that I wouldn’t like working in an office. I started wondering again where the ducks in Central Park went when the lagoon was frozen over, and finally I went to sleep.

The New Yorker finally published “Slight Rebellion Off Madison” in 1946. That same year, Salinger submitted a 90-page manuscript about Holden Caulfield to the magazine. It was accepted for publication, but strangely and suddenly withdrawn by the author. Over the course of the next five years Salinger would publish his most famous early works. His earliest and most cryptic Glass family story, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” appeared in 1948, followed by the string of pieces that would be collected in Nine Stories. In 1950, Samuel Goldwyn firmly established Salinger’s career by releasing My Foolish Heart, a Hollywood adaptation of “Uncle Wiggly in Connecticut” starring Dana Andrews and Susan Hayward. The title of the film, and its accompanying movie poster, which depicts Hayward and Andrews in passionate and orchestra-swelling embrace, were enough to prove that Hollywood got it all wrong. But Salinger’s embarrassment over My Foolish Heart was offset by the publication of one of his most moving and critically acclaimed stories, “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor,” in April of the same year. On July 14, 1951, two days before Catcher hit shelves, The New Yorker printed “Pretty Mouth and My Green Eyes.” Between “Slight Rebellion” and “Pretty Mouth,” Salinger’s career had exploded, making him not only a respected writer, but also a famous one. The straightforward angst of characters like Babe Gladwaller had been replaced by the searing and shaky breakdown of Sergeant X, and the chilling suicide of Seymour Glass. It had been five years since any member of the Caulfield family had been featured in a printed story. As far as anyone knew, Holden Caulfield was dead and gone.

¹ Ian Hamilton’s In Search of J.D. Salinger, page 39

² Margaret A. Salinger’s Dream Catcher: A Memoir , page 27

³ The Army soon lowered its medical standards for service and Salinger reported for duty on April 27, 1942 at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

Michael Moats completed his graduate thesis, a collection of essays on J.D. Salinger, and received his MFA from Emerson College in Boston. He recently reviewed J.D. Salinger: A Life by Kenneth Slawenski for AGNI Online. He blogs at Trade Paperbacks.