What is Women's Writing?

A Discussion at the Emily Books Symposium

“The idea in publishing used to be that men would never read women’s books, but women would read men’s books,” said Melissa Flashman, a literary agent at Trident Media Group. “I think that’s changing.” Women’s books, she said, are becoming hits on their own, with devoted and enthusiastic readers, and the big five publishing houses are catching on. We were in Liberty Hall, the sleek event space in the basement of the Ace Hotel in Midtown, and a crowd was starting to gather. Women in thick glasses and topknots placed their purses on folding chairs to save their seats; a line grew at the bar. A moment later, Flashman darted away to take her place at the discussion table at the front of the room. She was about to participate in a panel discussion, “What is Women’s Writing?” about the organizing question of the all-day symposium that took place at the Ace this past Saturday, organized by Emily Books.

Emily Books is an online feminist book distributor celebrating its fifth year, founded by Awl pals Ruth Curry and Emily Gould, both accomplished writers in their own right. The crowd at the Ace represented its cult following and increasing industry draw — the audience members who sat crossing their legs under Liberty Hall’s purple lights were predominantly young, white, and female, and everyone had the slightly frazzled air of an editorial assistant who works more than sixty hours a week for less than forty thousand dollars a year. The panel was composed of powerful literary women: Ecco editor Megan Lynch, National Book Foundation director Lisa Lucas, Caroline Casey of the Minnesota-based Coffee House Press, and Laia Garcia, an editor at Lenny Letter.

It was the best kind of intimate conversation: the panelists all got to complain. The question of what women’s writing is quickly turned to one of what women’s publishing is, just as in every industry the content of what women want to say is often eclipsed by the enormous efforts that they have to make just to be heard. The panelists talked about sexism in the workplace, of the dismissal of women’s concerns, of the editorial assumption that femininity and seriousness are mutually exclusive. During a debate about whether or not it was useful for ambitious, intellectual feminists to attempt to infiltrate and change what Gould called “elite cultural arbiter institutions,” Casey snorted. “Those institutions are already ours,” she said. “[Women] are all the people who work there. [Men] are just in charge.” The assistant crowd roared.

The panelists spoke, too, of the enforced differences between men’s and women’s communication, and of their formative moments of realizing that they could not or would not be allowed to talk the way that men do. “A man will say, ‘I’m going to do this,’ while a woman will say, ‘I hope to do this,’ said Lynch, speaking to the ways that women can be more cautious in their speaking than men, how they are careful not to seem too sure of themselves. “I didn’t realize until college that girls were supposed to be a certain way around men, to make them feel good about themselves,” Casey said. “Your male friends don’t want to hear about your period.” Lynch reasoned that “a conventionally feminine communication style can actually be a very effective way of getting what you want.” This might be true, but it’s still a concession to the grim idea that the easiest way for a woman to get what she wants is to convince a man that something was his idea.

Ultimately the group was enthusiastic, agreeing that the failures to accommodate women’s perspectives in publishing was eclipsed by the beauty of readers’ desire for them. Garcia talked about her dog eared copies of Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick and Kate Zambreno’s Heroines, two books that merge theory with frank memoir. “There’s been a privileging of emotional resonance,” in fiction, Flashman said. “Women readers want emotional depth at every level of the fiction market, whether they’re getting their book recommendations from People magazine or Instagram.” Several panelists cited the role of social media in creating a more active and connected market of women readers, who are able to discuss and recommend books with greater ease than ever before.

Garcia spoke of formative early experiences reading excerpts of feminist tracts on Tumblr; Lucas cited the hashtag #FeminismIsForWhiteWomen as opening up a conversation about exclusion, in fiction and elsewhere. “There’s a demand for more work by women of color that is not only about race, that depicts whole lives,” she said. “There’s more or a marketplace for it.” When Casey mentioned that Elena Ferrante had used the domestic sphere as a way to write about politics, all of the women nodded, almost in unison.“There’s been a change in what subject matter, perspective, and scope is appropriate for a literary novel,” Lynch said. At the beginning of the night, Curry and Gould had said that their aim with Emily Books was to help create a literary world that was more accessible to those who were not “white, heterosexual, and male.” The women’s testimonies suggested that slowly, that world is becoming more real.

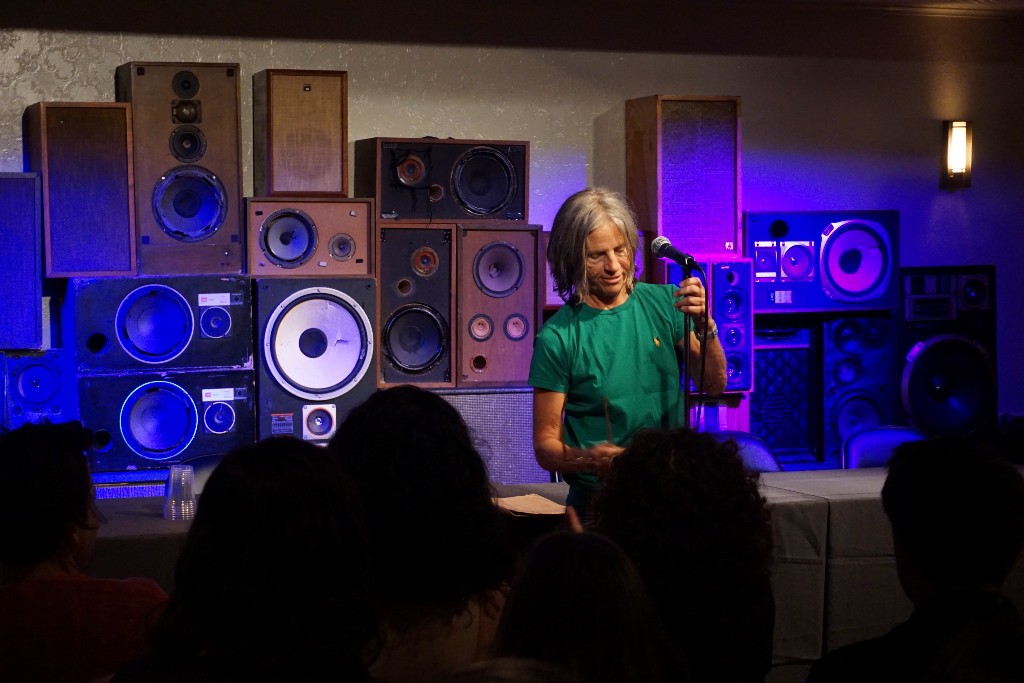

After the panel disbanded there was a cocktail hour, and women moved through the narrow aisles between the chairs; they bumped tote bags passing back and forth from the bathroom and stood in small clusters taking enthusiastically, clutching clear plastic cups of wine. Then everyone settled back down for a series of readings by Emily Books authors. Eileen Myles wore a Kelly green tee shirt and read a passage about a trip to Ireland from a forthcoming book; Natasha Stagg read a dark, funny passage about the beginning of a stalking relationship from her Semiotexte-published novel, Surveys. The poet Ariana Reines wore a dress painted with a scene of city buildings on fire. When she stood up to read, she said by way of introduction, “I’m going to read a love poem really fast.” The poem included the line, “I used to think the defining characteristic of a writer was not wanting to have her picture taken, ever.” Everyone in the audience chuckled; some of the women held up their phones for a photo.