Our Lady of 'Truth or Dare'

Watching the Madonna documentary, twenty-five years later

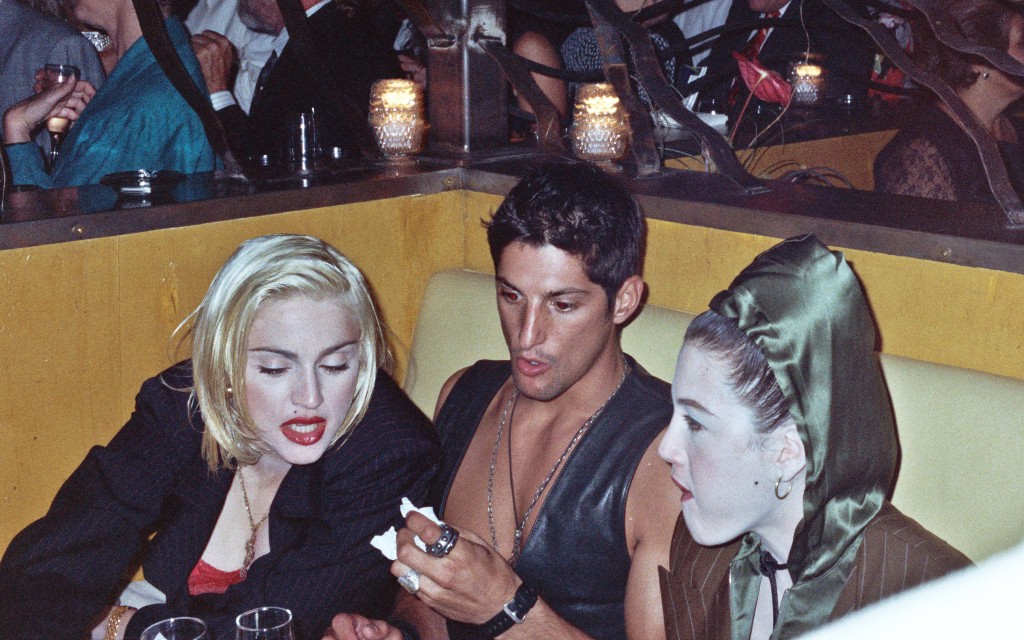

Madonna: Truth or Dare came out 25 years ago. Released to the most favorable reviews of her cinematic career, the film is about how Madonna lived her life on the Blonde Ambition tour. Arguably, Blonde Ambition was the apex of an era; the tour grossed $60 million, sold out every night except the cancelled date in shocked-and-Catholic Italy, and introduced the enduring image of the singer in a pink satin cone bra. In 1991 the public knew — and, more importantly, bought — what Madonna stood for: a sensual hunger for money; an obsession with black or latino Others that verged on problematique; the novelty of female sexuality; the exchange between strangers on the dance floor, under bridges, in booths; the fruits of risking it all for your artistic dreams; and hair, always hair. If one person embodied this much, did she ever get any sleep?

Outside of North America, the film was titled In Bed with Madonna, and that’s what we get, figuratively speaking. We see the bed that Madonna made, what she’d eventually call her erstwhile playground. From here you can draw a crooked line not just to nouveau pop stars in Madonna’s debt, but also the Kardashian-Wests and their in-laws, the Jenners, the Hadids — the entrepreneurs, for lack of a more exciting word, who build emotional and lucrative narratives around lips, eyebrows, dye jobs, weight loss, woo-woo spirituality, capital obsessions, love affairs, sex tapes, and, most of all, the white heat that comes from a person who knows what she wants. This is a movie about entitlement as much as it is about intimacy, fame, and beauty. From here we learn that entitlement suggests, but never confirms, that the person might know where she’s going. But does Madonna know where she’s going?

I like Truth or Dare because nothing really happens in it. There’s obviously a lot to talk about, but still: “Madonna does her job” is the log line. No one breaks up, no one dies, and no one quits the business. There’s Warren Beatty, Madonna’s beau of that moment, complaining that she never wants to have conversations off camera. There’s the ghost of David Fincher, who almost did the movie but bailed; by that point, he had directed three Madonna videos, including the similarly black-and-white “Vogue.” There’s Kevin Costner (!), calling the show “neat.” There’s the strung-out woman who shows up at a hotel and claims Madonna fingerbanged her when they were teens. There are the dancers who would later sue Madonna for misrepresenting them in this film, but there are also other dancers — beautiful, young, and yes, brown — with a type of joy in their queerness not often seen on film in those years. People drift in and out of a world that Madonna built, on the backs of a lot of people.

“Madonna does her job” is the log line.

I also love Truth or Dare because it’s weirdly warm. It’s a product of both an artist’s controlling nature and her instinct to let go a little bit, to be oblivious sometimes and a little wobbly. Her mic sometimes cuts out onstage; she’s sometimes tired, in her bathrobe, whining on the phone while slurping soup. And yet the film represents a career highlight with pride, without much discretion, but with some version of taste, like youthful nudes hung in the guest bathroom. The relationships between everyone on the tour seem more familial than most, and Madonna’s voiceover is beautiful, even when she complains. She knows how to confess. There is real melancholy, too — Madonna visits her mother’s grave, wondering about virtue; she says things about Sean Penn that make you sad for her, for them, for love. In hindsight, there’s also an element of “before the party ends” to the proceedings, before things get a little bit less queenly for the queen of pop.

On a lot of levels the film is fantasy, and one of those levels is political. Madonna’s choice to acknowledge Keith Haring’s death from AIDS in her show monologue, for example, is now ironic given the silence of three Blonde Ambition dancers living at that time with HIV. And the empowerment championed in “Express Yourself” is a little bit like a gift you know the giver wants mainly for herself. At this and every point in Madonna’s career, she is self-involved to the point of myopia, maybe blindness. When she picks “truth” in the eponymous game, someone asks her who the love of her life has been. “My whole life?” she asks at the age of 31, and she answers with tenderness: “Sean. Sean.” You know: a man who allegedly beat her with a baseball bat in Malibu.

When you watch Truth or Dare, it’s easy to catch up with what had already happened to the star, but try to wrap your head around what had yet to occur. There was so much left: Argentina, Antonio Banderas, Kabbalah, rays of light, Ali G and cowboy hats, Gwyneth Paltrow, macrobiotics, the absence of crying in baseball, the grace of Courtney Love, London accents (or something like them), a kiss with Britney Spears, a kiss with Christina Aguilera, many kisses with Rupert Everett, alleged alcoholism, a surprisingly fine James Bond theme, a forgotten song on an Austin Powers soundtrack, ABBA samples and deep squats on rollerskates, extremely misguided and semi-racist Instagrams, a performance at the Super Bowl with M.I.A., of all people, and a lot more of the same, a tireless kind of sturm und drang with less and less punch as Madonna’s brand of turbulence became the norm. No one can contest this woman’s endurance, and her relevance became moot — who cares? She really doesn’t.

One reason people hate Madonna, besides her long career of exploitation, is she tries so hard. Too hard, really, and for what these days? All of the above can be read as pointless desperation, and it often is. In the context Madonna established, it makes sense that an artist whose subject is both romantic and spiritual thirst would come on too strong, especially late in the game. But why does she still care so much? And why doesn’t it work anymore, beyond a crew of yes men and women who are determined to laugh at every joke and play every game?

One reason people hate Madonna, besides her long career of exploitation, is she tries so hard.

Let’s say that 1991-era Madonna is a blueprint for a type of person who is so famous that the initial product is besides the point. She’s an empire-builder, not always respected for her art, even though she is the only person to do it her way. If we follow this logic to its ultimate end, we must ask: Are the twilight years of such a person inevitably filled with hollow recreation? What will happen to Kanye West? Nothing terrible, one hopes. It’s not inherently bad to fade away, surrounded by your favorite things. But the meaning of the circus changes. Its vitality becomes way more foreboding.

In 1991, Madonna was a totem of the present. Now, Madonna is an icon of mortality. Even her hits about life make me think about life’s end. Remember how all the legends listed in “Vogue” are dead now? Or how about “Like a Prayer,” in which she insists that everyone ultimately must stand alone? On her last album, honest to God, one of the lyrics is “I want to die,” sung with plaintive pathos; I don’t think any other pop star makes me think about death so much. In the words of Madonna’s last truly great song, time goes by, so slowly. Especially for those who wait.

Think of it: Madonna was once a metonym for oversharing. In my favorite song of hers, “Burning Up,” she sings: “Unlike the others, I’d do anything.” She warned us from the beginning, really. From a book about sex — not just her sex life, but sex, as a concept — to paparazzi photos of her shopping for vibrators, this woman had no shame. Doesn’t it make sense then, that instead of a voice whispering, “Remember you must die,” Madonna’s memento mori is an oddly artsy, warmly told tell-all film? It’s her own voice, not a lackey’s, reminding her she’s just human, and it’s louder than you’d expect. It made it through the wilderness, one time too many. “Truth or dare?” the voice asks. And Madonna chooses both, always.

Madonna: Truth or Dare opens at The Metrograph on August 26 and runs through September 1.

Jen Vafidis is a writer. She has previously written for Rolling Stone, Gawker, The Awl, and Cosmopolitan.